In the United States, Tuesday, November 2, 1948, was election day. Almost 48,000,000 Americans voted, including to choose the next president.

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Robert H. Jackson was not one of the voters. He had stopped voting when he had become a justice, in 1941. Jackson believed that a Supreme Court justice should not express, even in a private voting booth, a preference for a political candidate.

But Jackson was very interested, all his life, in politics. He had been an active Democrat. His interest in politics did not disappear when he became a justice.

In Fall 1948, Jackson was particularly interested in the presidential race because he knew well the two leading candidates.

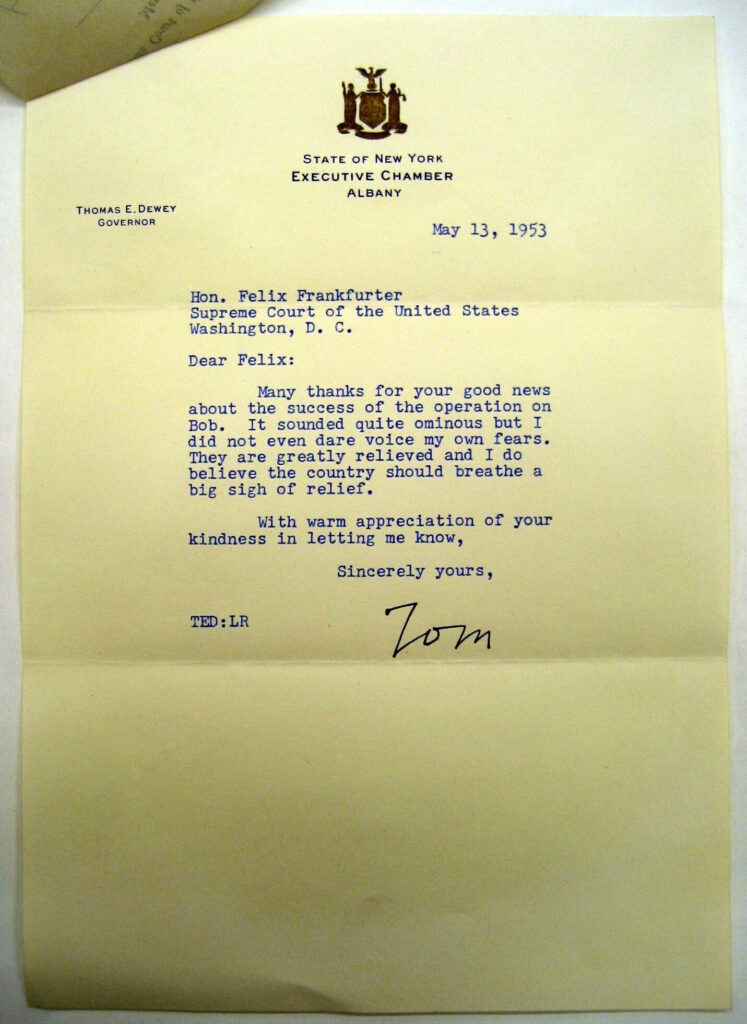

Jackson had known the Republican presidential nominee, New York governor Thomas E. Dewey, since 1934. They met when Dewey, then a U.S. Department of Justice lawyer, worked on tax prosecutions alongside Jackson, then a senior U.S. Treasury Department lawyer.

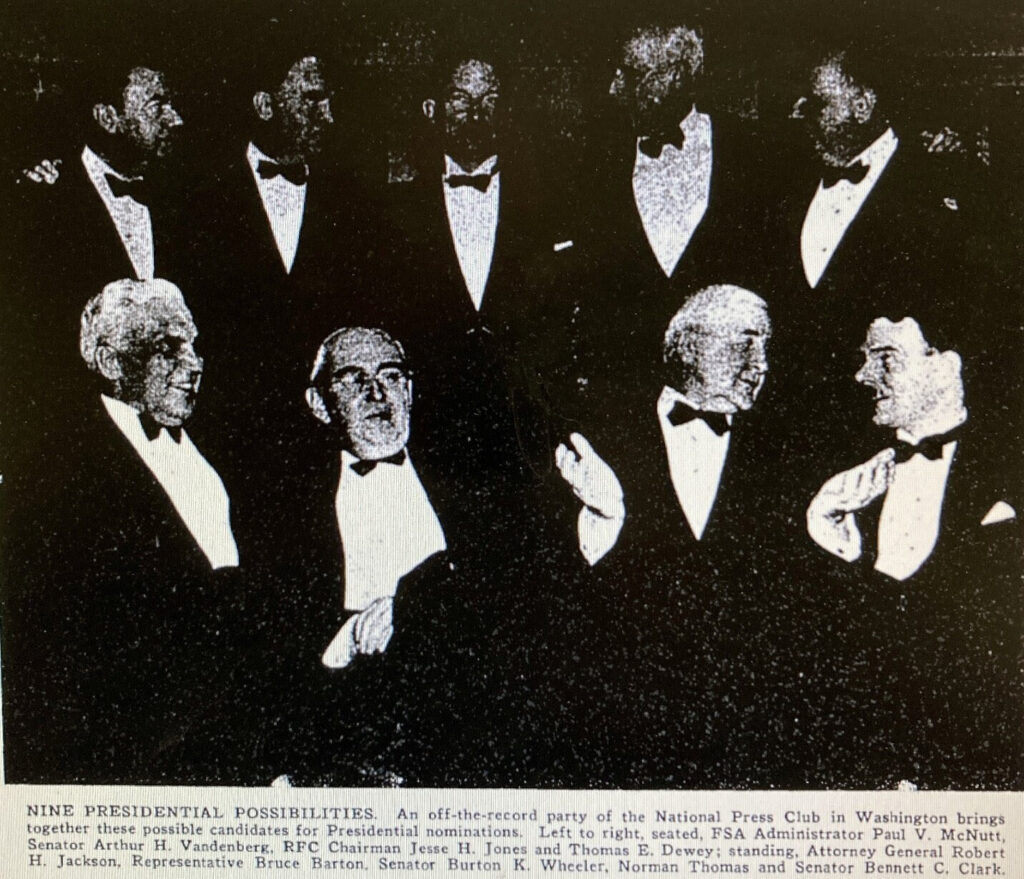

Thereafter, through their rising legal careers, political activities, and law enforcement work in New York and Washington, Jackson and Dewey crossed paths regularly. Indeed, as each became a leading national figure in his political party, it seemed that Jackson and Dewey were destined to run against each other as candidates for a top political office. For example:

- In early 1938, it seemed that New York governor Herbert Lehman, a Democrat, would not seek reelection, that the Democrats might nominate Jackson (then a senior U.S. Department of Justice official) to succeed him, and that the Republican candidate would be Dewey (then the Manhattan district attorney). But Lehman decided later that year to run, and he defeated Dewey.

- In early 1940, it seemed that President Franklin D. Roosevelt was retiring after two terms, that the Democratic Party presidential candidate might be Jackson (then the U.S. attorney general), and that District Attorney Dewey might get the Republic nomination. But Roosevelt did run, Dewey did not get his party’s nomination, and FDR of course won his third term.

- In 1944, Dewey, who had won election as New York’s governor in 1942, won the Republican Party presidential nomination. If Roosevelt had not run then for a fourth term, … But he did, and he won.

- In 1946, when Justice Jackson was prosecuting Nazi war criminals in Nuremberg, Democratic Party leaders wanted him to come home, resign from the Supreme Court, run for governor of New York and defeat Governor Dewey, … Jackson said no thanks. He stayed at Nuremberg, and on the Court, and Governor Dewey won reelection.

Dewey’s 1948 presidential campaign opponent was, of course, the incumbent, if accidental, president, Harry S. Truman. He had been FDR’s vice president for less than three months when the president died in April 1945.

Two weeks after Roosevelt’s death, President Truman recruited Justice Jackson, whom he knew and admired greatly, to represent the U.S. as chief prosecutor of the top Nazi war criminals.

Truman’s inherited presidential term was not smooth. But in 1948 he decided to seek election in his own right. He won his party’s nomination. That fall, he campaigned hard, ignoring all the smart people who knew and said that he was doomed to lose to Governor Dewey.

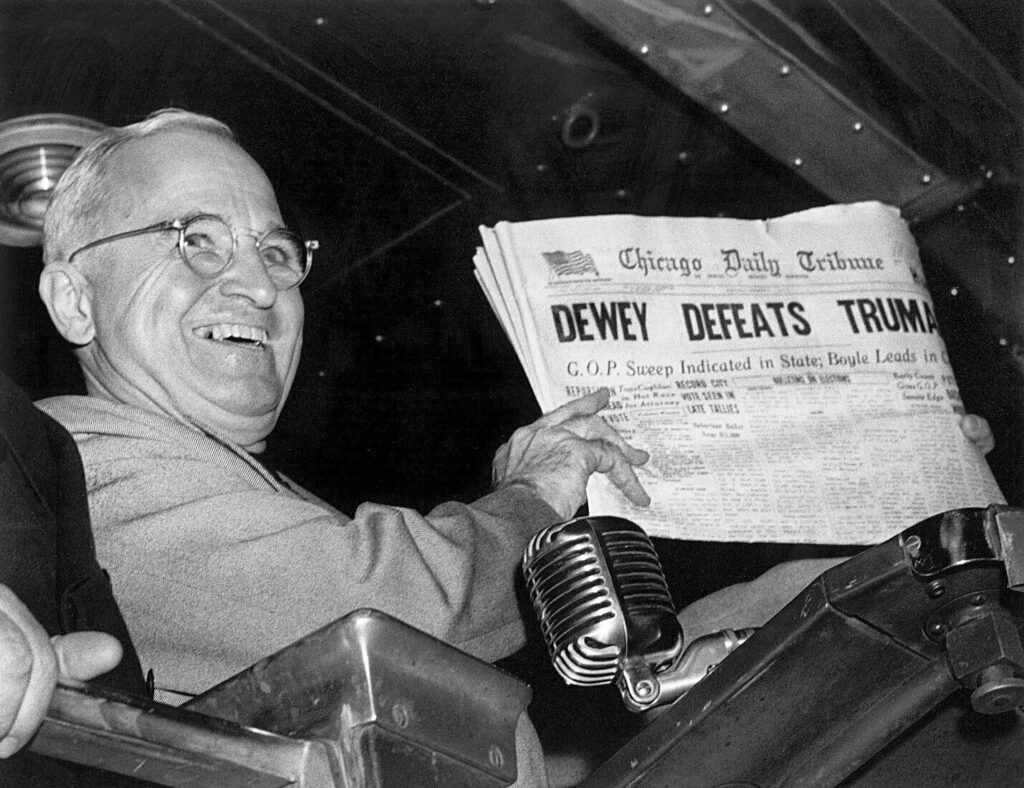

Two days after the election, on November 4, 1948—seventy-five years ago on this date—President Truman, at Union Station in St. Louis, Missouri, spotted a typo in the November 3 Chicago Daily Tribune early edition headline:

I suspect that Justice Jackson was, like many people, a bit surprised by the result. To my knowledge, Jackson had not predicted a Dewey victory. Jackson had, in a private letter to his son that he dictated on Election Day, joked negatively about candidates Dewey and Truman and all politicians. Jackson said,

I suppose we will know the verdict by midnight tonight. But I feel a little like the fellow I heard of, who said, “Thank God I don’t have to vote for both of those fellows!” I don’t know what the changes will be, but I am sure [that] many of them will be for the worse.

Jackson did not really believe that. He thought well of politics, of elections, of voters, and of participating in democratic self-government. He thought well of politicians, including Truman and Dewey.

It is interesting to imagine a Jackson-Dewey political race. It would have featured hard campaigning, substantive disagreements, and mutual regard—the right things.