During the United States Supreme Court’s 1944-1945 term, the Justices heard three final days of oral arguments in the week that began on Monday, April 30, 1945.

Justice Robert H. Jackson missed some of these arguments. He might not have been fully prepared for those that he did attend. In that week, the argument cases and Supreme Court work were not his primary concern.

Beginning on April 25, 1945, President Harry S. Truman had recruited Justice Jackson to represent the U.S. as its chief prosecutor, with allies, of the Nazi German leaders who were on the brink of being defeated militarily and captured. Since then, Jackson had been reading secret executive branch planning documents, meeting privately with the President and other executive branch officials, assembling staff, editing the President’s coming order and announcement of Jackson’s appointment, drafting his own statement, confiding in and getting advice from family and selected close friends, and having other meetings and conversations on this topic.

On Monday, April 30, Justice Jackson traveled from his rural home (Hickory Hill in McLean, Virginia) to the Supreme Court. He had morning telephone calls with President Truman and with White House Counsel Samuel I. Rosenman. At noon, Jackson, with all of his fellow Justices, took the bench. The Court announced a decision and then heard oral arguments in three cases.

On Tuesday, May 1, Justice Jackson did not go to the Court. He worked from home, reading documents, writing a memorandum on an executive branch prosecution plan, and speaking by telephone to the Secretary of War, Henry L. Stimson. In the afternoon, Jackson hosted a meeting of senior Department of Justice and War Department officials, which Judge Rosenman joined in the late afternoon. Jackson missed Supreme Court oral arguments that day in four cases.

Justice Jackson did attend on Wednesday, May 2, 1945—eighty years ago on this date.

The Justices took the bench at noon. Chief Justice Harlan Fiske Stone admitted attorneys to practice before the Court. Then the Justices heard oral arguments, the final ones of the term, in two pairs of consolidated cases.

In each argument, one of the advocates was William Dwight Whitney, partner in the New York City law firm of Cravath, Swaine & Moore. Justice Jackson had seen Bill Whitney argue before the Court earlier in the term. Whitney impressed Jackson. The next day, he recruited Bill Whitney to join his Nazi war crimes prosecution team, where he became a significant contributor.

One of Whitney’s oral argument co-counsel on that day was another New York City lawyer, John M. Harlan. He and Jackson also came to be acquainted, including after President Eisenhower appointed Harlan in early 1954 to be a Judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit. (Following Justice Jackson’s death in late 1954, Judge Harlan was appointed to succeed him on the Supreme Court.)

At some point on May 2, 1945, Chief Justice Stone and the seven other Associate Justices learned that Justice Jackson would be working for President Truman as U.S. prosecutor of Nazi arch-criminals. Jackson had not confided in or consulted any Justice when he was recruited. Nor had Jackson disclosed to any of them in advance that he had accepted the appointment, even though some could see it—Jackson did, and we do—as in tension with the separation of executive and judicial powers, and as risking leaving the Court short-handed for some period of time.

I believe that Jackson told his “Nazi prosecutor job” news to his fellow Justices on the morning of May 2. Maybe he did so in the Court’s robing room, just before they took the bench that noontime.

Jackson’s news might have distracted some Justices during that afternoon’s oral arguments.

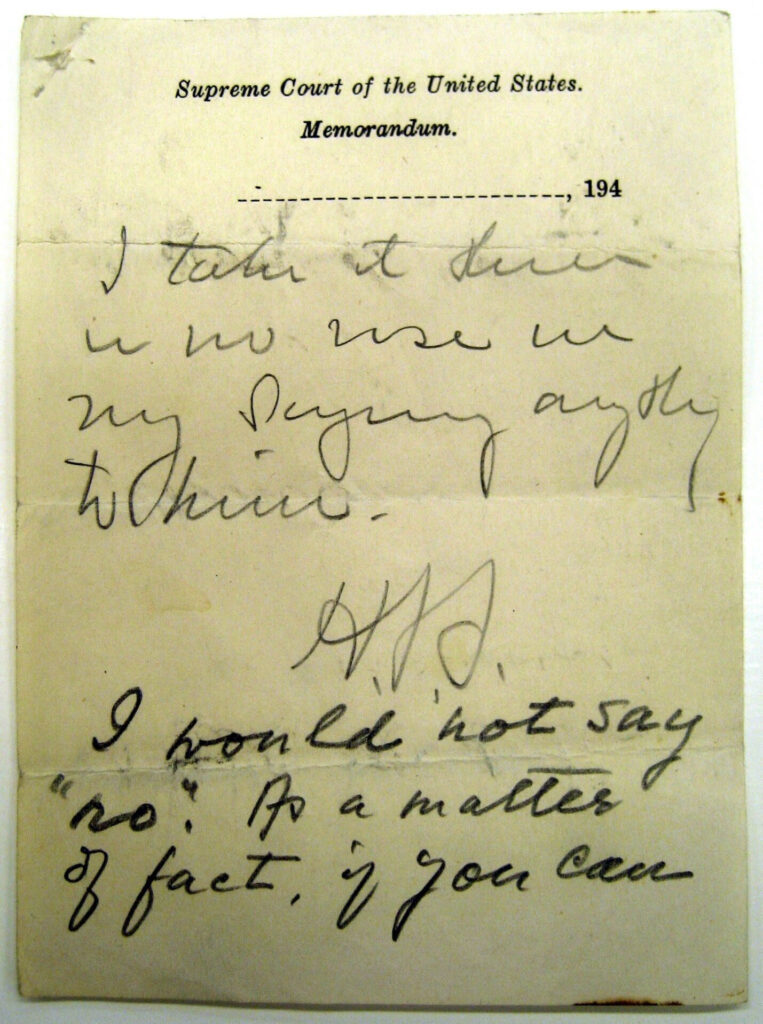

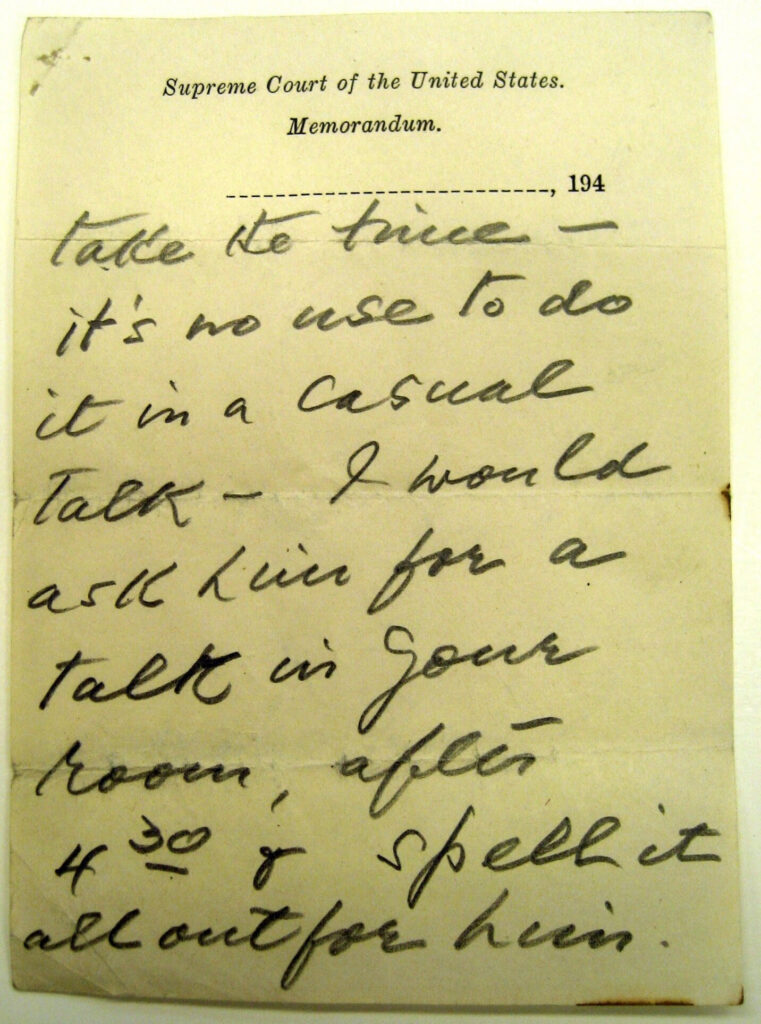

Indeed, Jackson’s news might be the subject of these undated notes that Chief Justice Stone, who was on good terms with Jackson, and Justice Felix Frankfurter, who was Jackson’s closest friend on the Court, scrawled and passed to each other on the bench during some Court session on or before this day:

I take it there

is no use in

my saying anything

to him.H.F.S.

I would not say

“‘no.” As a matter

of fact, if you can

take the time –

it’s no use to

do it in a casual

talk – I would

ask him for a

talk in your

room, after

430 + spell it

all out for him.

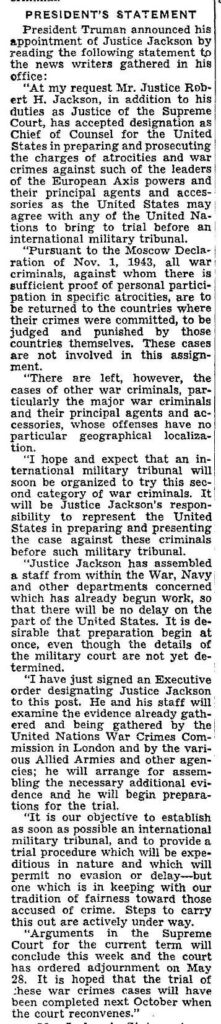

At the White House, President Truman held a Press and Radio Conference in his office just after 4:00 p.m. He read a statement announcing his appointment of Justice Jackson:

(President Truman also signed Executive Order 9547 that formalized his appointment of Justice Jackson—click here.)

Back at the Supreme Court, the Justices had adjourned until the following Monday, May 7, when they would return to the bench and announce decisions. (On that day, Justice Jackson was present for the first part of the session, but then he left the bench to attend to other matters.)

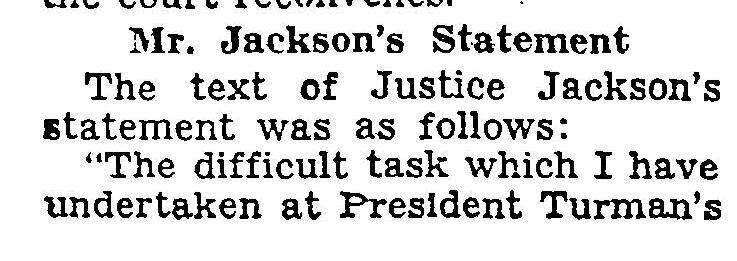

On May 2, after President Truman had announced Justice Jackson’s appointment, Jackson released his own statement to the public (and he circulated a copy of it to each member of the Court):

Late that afternoon, Justice Jackson posed in the Court’s West Conference Room for press photographs.

Jackson sat beneath the portrait of Chief Justice William Howard Taft.

But Jackson was no longer, principally, on the job of being a Justice of the Court. He now was U.S. Chief of Counsel; he would be, soon, in Nuremberg, the U.S. chief prosecutor of Nazi war criminals. He was working

“to do something toward bringing to a just judgment those who have heretofore thought it safe to wage aggressive and ruthless war; and to do it in a way that will be consistent with our traditional insistence upon a fair trial for any accused.”