In Spring 1945, Mary Frances Langworthy was eighteen years old. She had left high school without graduating, to work. In that final year of World War II, she was employed in the Washington, D.C. area as a secretary in the United States Department of War.

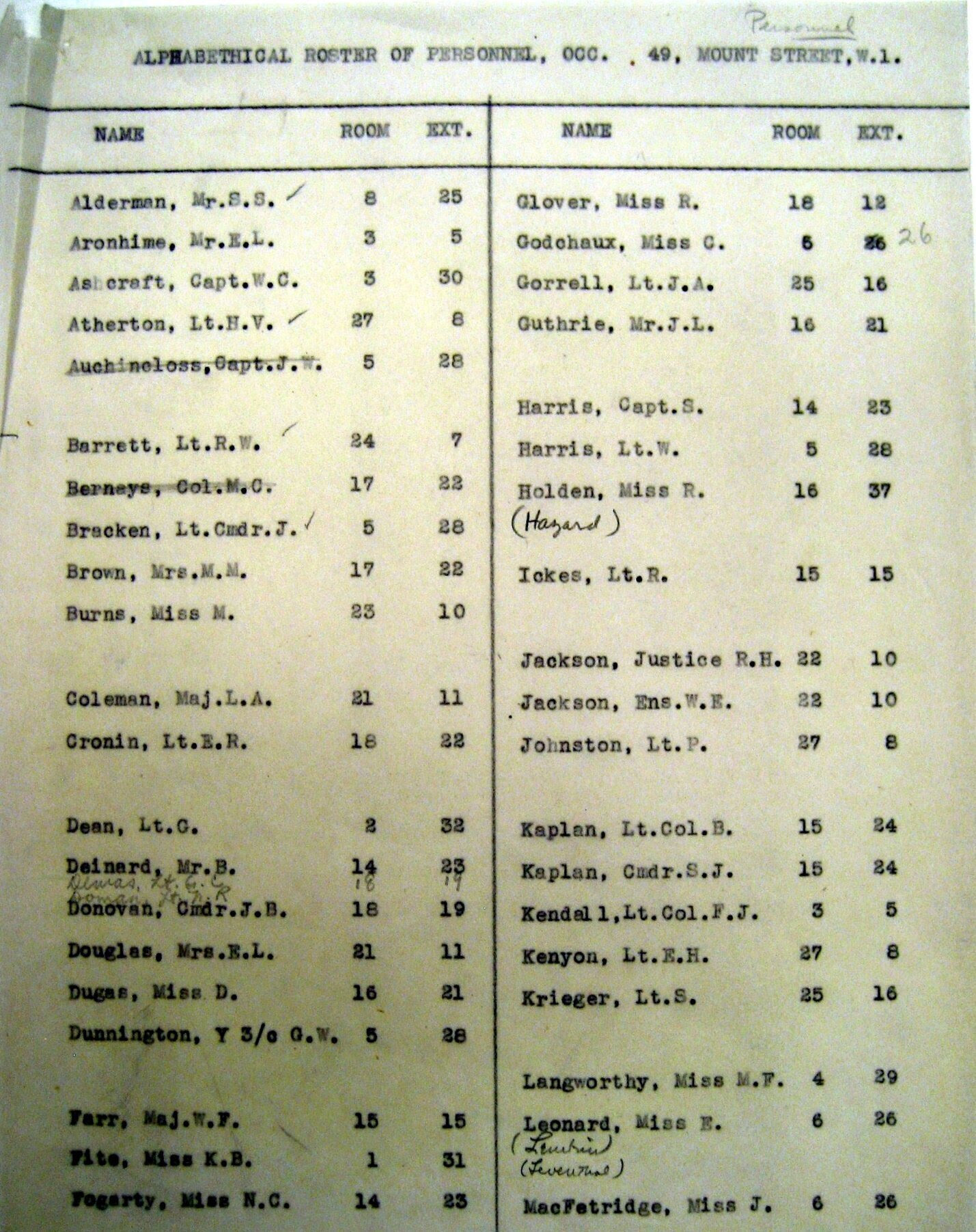

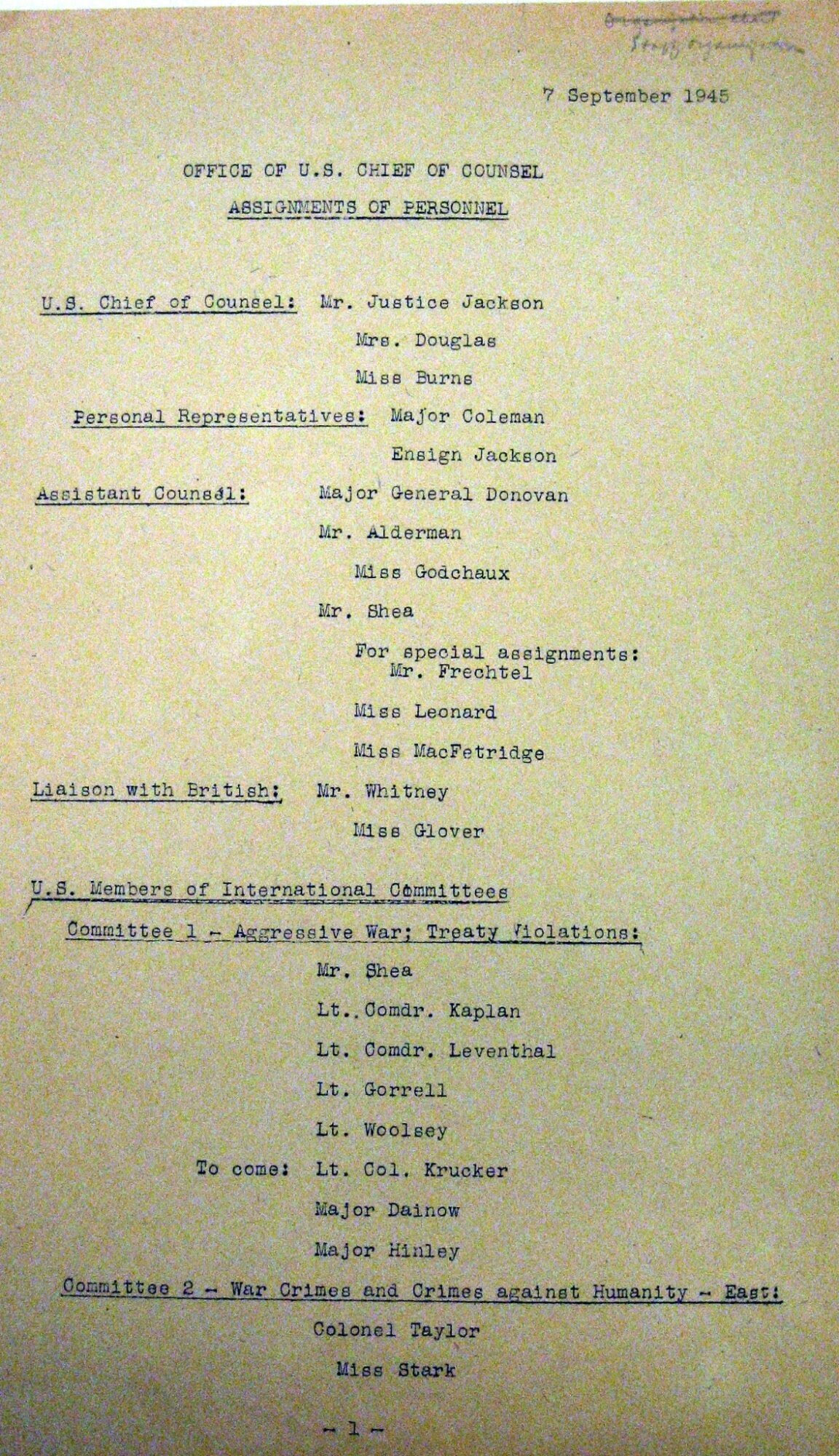

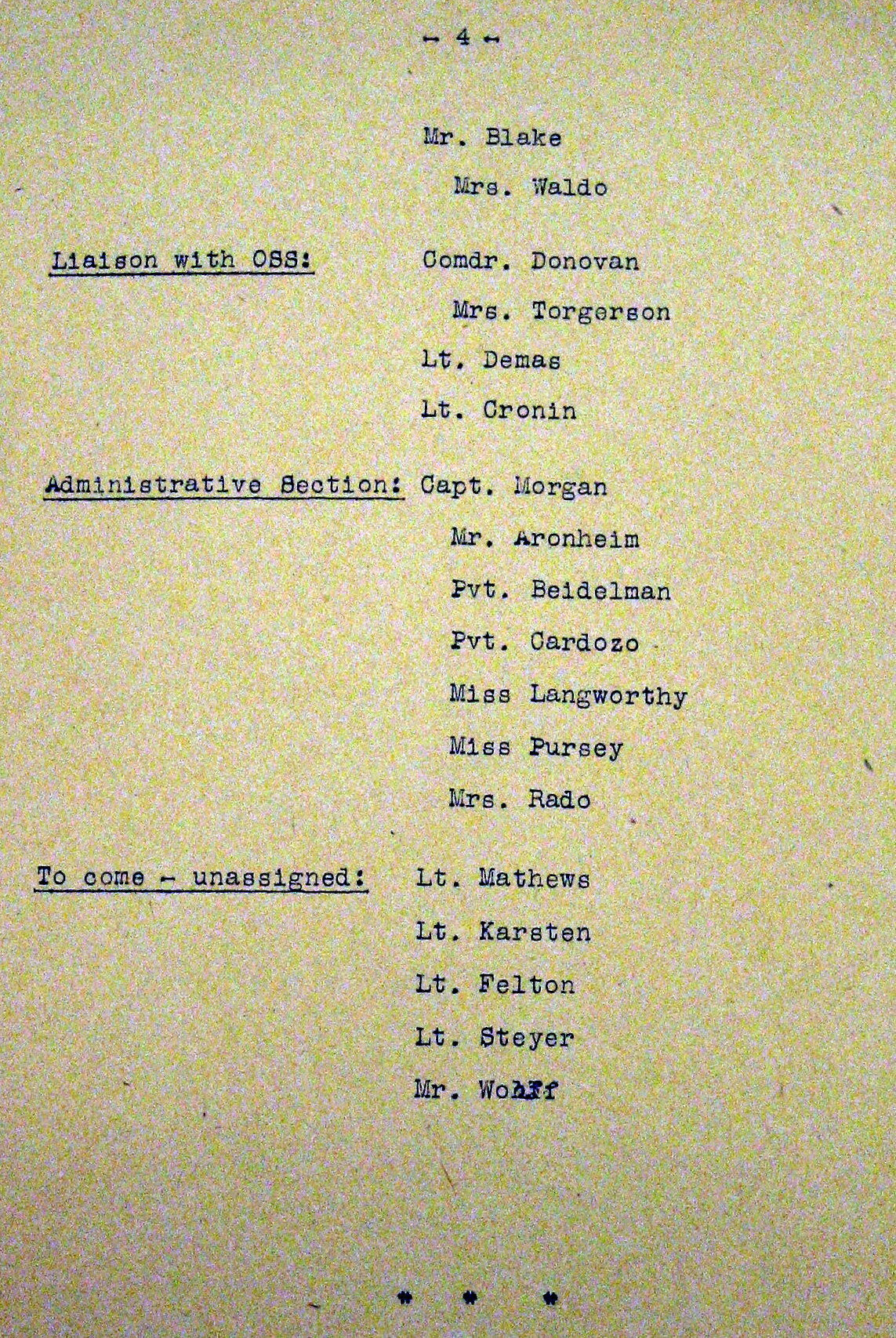

In Summer 1945, Miss Langworthy’s work became an international adventure. She was detailed to travel to London to join the Office of United States Chief of Counsel for Prosecution of Axis Criminality—the OCC, Justice Robert H. Jackson’s Nazi war crimes prosecution team. Jackson then was negotiating with Allied government counterparts to devise the plan to prosecute surviving Nazi leaders as international arch-criminals while also supervising the U.S. investigative staff in Washington, London, Paris, and elsewhere.

Langworthy and others arrived in London to join Jackson’s OCC on Saturday, July 7, 1945.

The next day, Sunday, July 8, happened to be her 19th birthday.

Justice Jackson, who was away from London that weekend on a reconnaissance trip to the European continent, knew that Langworthy would be arriving on Saturday, July 7, and that the next day would be her birthday.

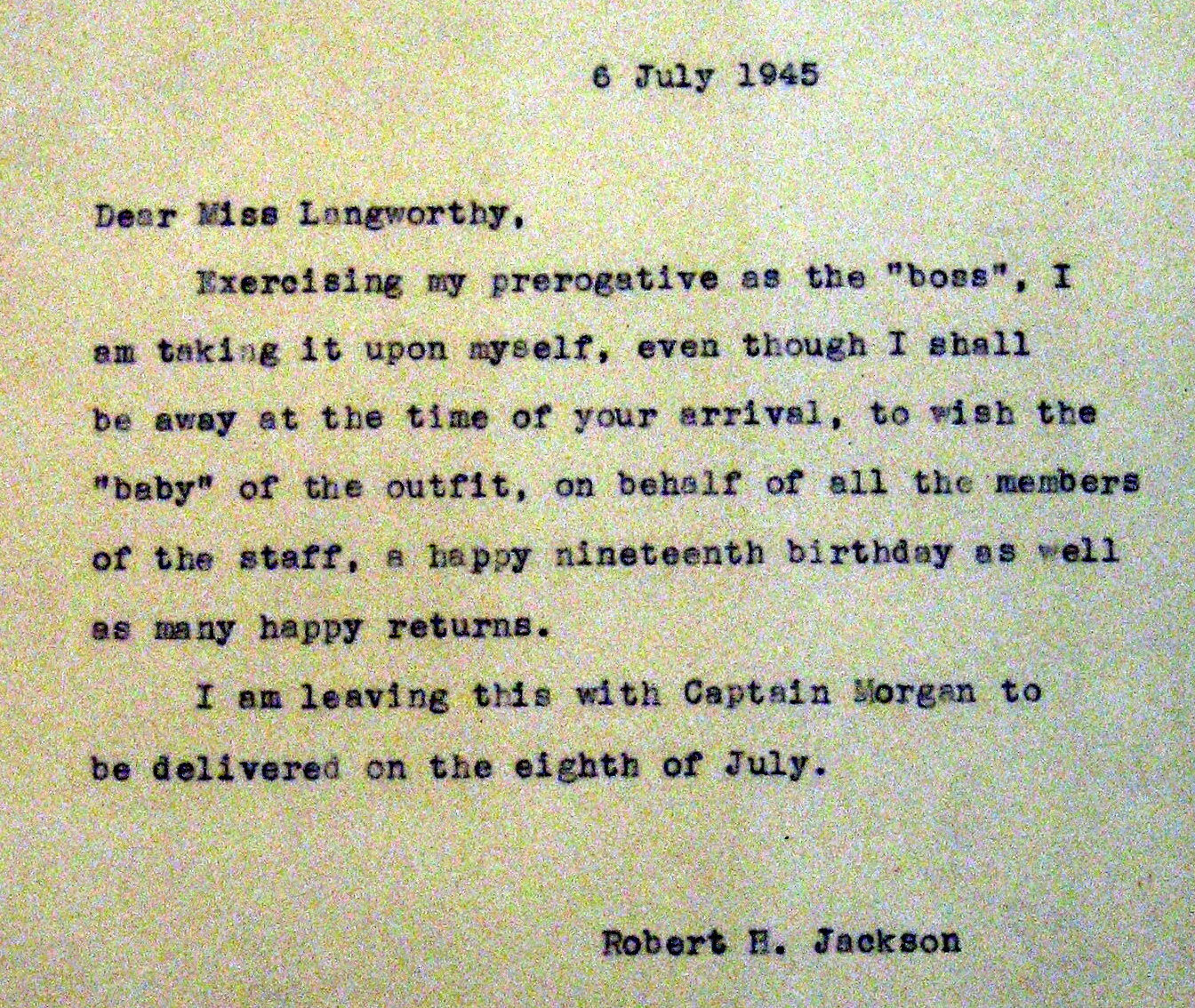

So on Friday, July 6, Jackson, before he embarked on his trip, dictated greetings to Langworthy, had them typed, signed the paper, and left it for staff to deliver to her on her birthday.

On July 8, Jackson’s administrative officer, Captain Ralph L. Morgan (Adjutant Generals Department), gave Langworthy this gift from Justice Jackson:

Actually, Justice Jackson did no such thing.

Indeed, I doubt that he heard of Miss Langworthy until the following week.

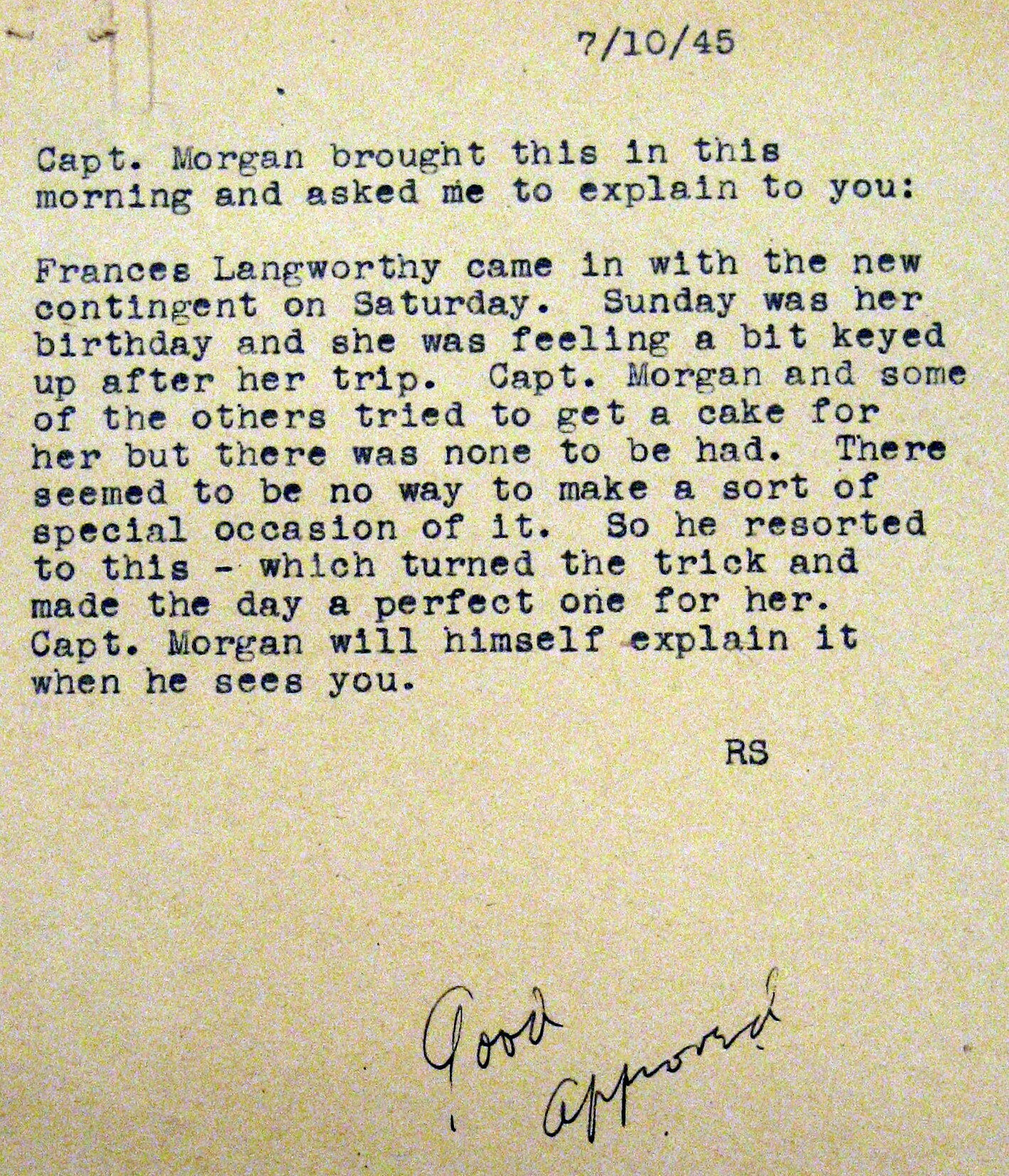

Jackson returned to London on Wednesday, July 11. In his office “In Box,” he found a note, typed by his secretary. It was paper-clipped to a carbon copy of “his” birthday note to Langworthy.

The cover note memorialized Captain Morgan’s confession, with explanation, that he had forged the “Jackson” note to Langworthy.

Justice Jackson, who was notably kind throughout his life to underlings, and who liked Ralph Morgan, was not irked. In fact, Jackson was pleased. He noted his approval on the confession and put it in his “Out Box.”

In Summer 1945, Fran Langworthy worked as a secretary on the OCC staff in London.

In September 1945, she became part of the large OCC staff in Nuremberg. She worked as a secretary in its offices in the Palace of Justice (the courthouse), assisting Captain Morgan and typing up translators’ and interpreters’ notes.

Langworthy’s work there continued for some months. But she left Nuremberg before the trial concluded in Fall 1946.

Following Nuremberg, Fran Langworthy, later Fran Cronin, later Fran Potter, lived a long life. Across all of it, a highlight, which she sometimes discussed publicly, was Nuremberg and her work for the OCC.

In August 2024, Fran Potter died at age 98. She was, I believe, the last living member of Justice Robert H. Jackson’s OCC.

In two days, we will mark the 80th anniversary of the start of the Nuremberg trial.

Nuremberg was a high achievement of the rule of law, of fair prosecution, and of due process. It held individual perpetrators accountable for grave crimes. It produced a vast historical record, available for study and teaching ever since, of what Nazi Germany was and what Nazis did. Nuremberg was justice, in fact and in symbol. It created legal precedents that successors have followed and built upon.

And Nuremberg was done, intentionally, by individuals—it was the achievement of Allied nation leaders and their personnel.

For the United States, the achievements of Nuremberg—choosing the path of law, then planning the first international criminal court, and then conducting a public trial competently and fairly—were in large part the OCC’s, from its boss to its baby.

Remember each of them with admiration and gratitude.

* * *

- Some links—

Here is video of a 2016 Fran Potter interview: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vfMxeAkYyPI - Here is a 2016 newspaper profile of Fran Potter: https://www.pennlive.com/news/2016/10/i_had_no_desire_to_look_into_t.html

- Here is Fran Potter’s August 2024 obituary: https://www.malpezzifuneralhome.com/obituaries/Mary-Frances-Fran-Potter?obId=32661163