During summer 1945, Justice Robert H. Jackson, President Truman’s appointee to serve as United States chief of counsel for the prosecution of Nazi war criminals, negotiated in London with British, Russian, and French counterparts. During more than six weeks of complex talks, they created the International Military Tribunal (“IMT”), defined crimes within its jurisdiction and procedures for its operation, gathered and analyzed evidence, and preliminarily identified targets for possible indictment.

In the course of the London talks, the Allies considered, among many issues, where to hold the international trials of captured Nazi leaders. They agreed generally that trials should occur in the former Germany, which had surrendered and the Allies now occupied. To ensure the security of both the Allies (against threats from Nazi military remnants) and the defendants (against threats from anti-Nazi German people), the U.S. Army strongly recommended the southern German city of Nuremberg, located in the U.S. occupation zone. Nuremberg had largely intact facilities that could serve as trial venues.

On Saturday, July 21, 1945, Justice Jackson flew, with members of his staff plus British and French colleagues, to Nuremberg on his U.S. Army airplane. (The Russians declined to join them.) They found a devastated region and city—Nuremberg’s walled old city and parts outside the walls had been largely obliterated by Allied bombing late in the war. The delegation also saw, however, the resources and capacities of the occupation. For example, at a welcoming lunch in the Officers’ Mess in Nuremberg’s Grand Hotel (itself significantly bomb-damaged but already under repair), they enjoyed what Jackson described as a Delmonico’s-quality lunch.

Justice Jackson and his colleagues then made a series of facility inspections. They visited Nuremberg’s Palace of Justice, a large courthouse and adjoining prison. They agreed immediately that this should be the trial location.

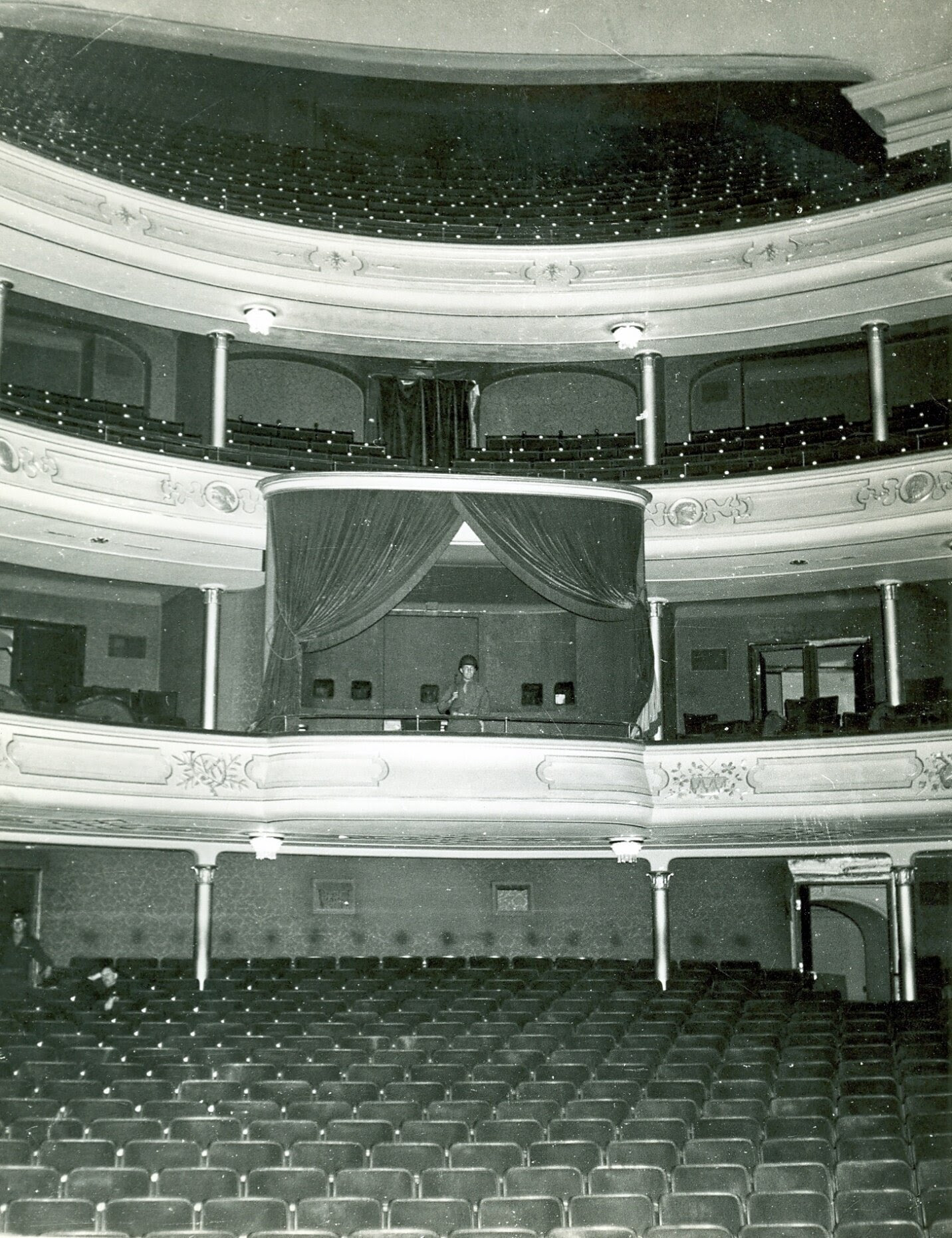

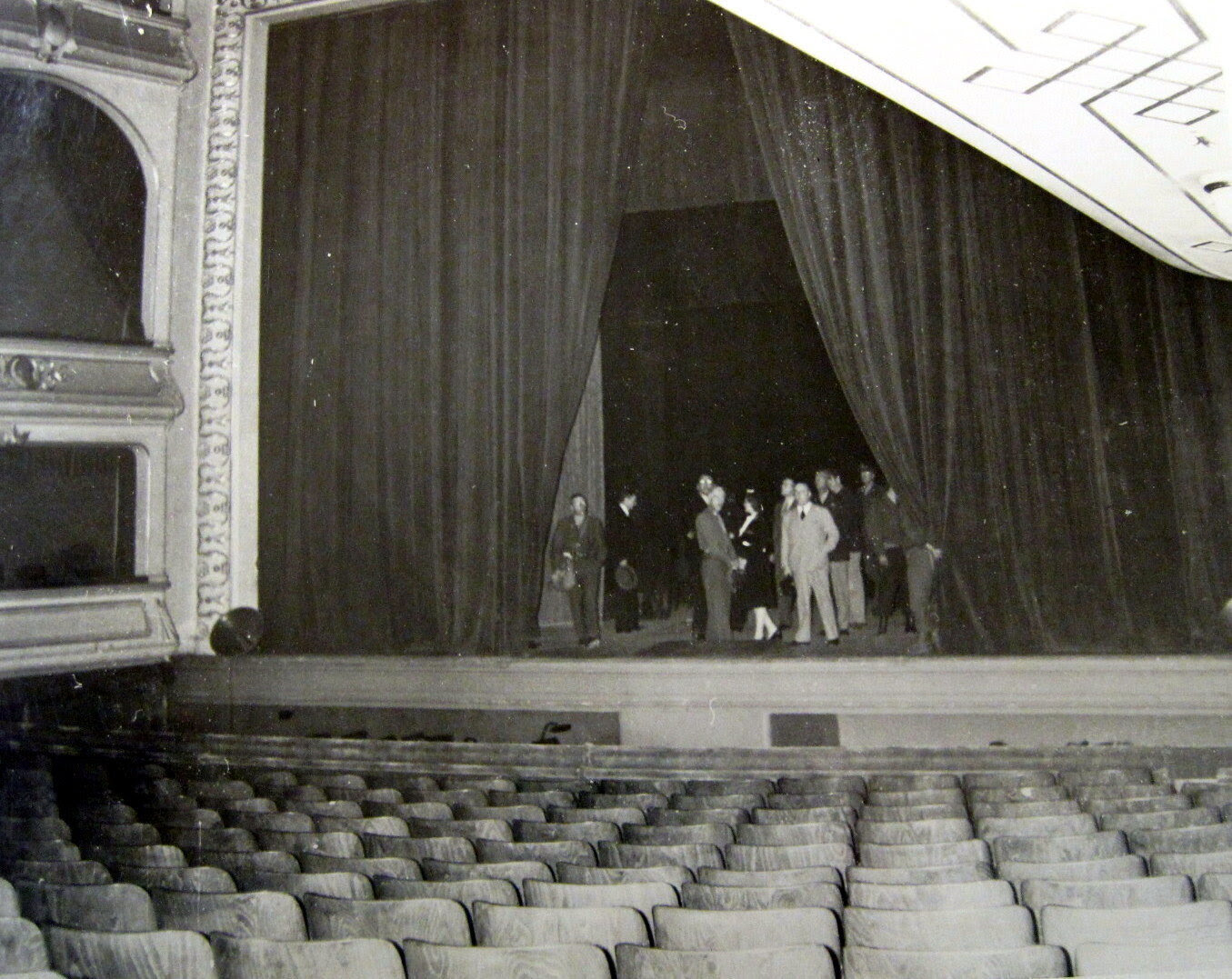

They also visited Nuremberg’s massive Opera House, located just outside the old city walls. Although the surrounding streets were filled with rubble and the building had suffered significant bomb damage, the main concert hall—large, ornate, with three balconies including “the Führer’s box”—was intact and functioning.

The next afternoon, the Allied visitors returned to the Opera House. They listened to a 50+ piece German orchestra perform Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony (which had become a musical symbol of the Allies’ war victory). Although the players performed without much enthusiasm, the Allies were understanding—as Jackson noted later that afternoon on his flight back to London, the German orchestra’s small audience that day consisted entirely of nationals of the former war enemies who had destroyed the city. Under the circumstances, Jackson and his colleagues agreed, the concert was well done.

Four months later, at the Palace of Justice, the war crimes trial of principal former Nazi leaders commenced before the IMT.

David Warren Brubeck was born in Concord, California, on December 6, 1920. His father became a California cattle rancher. His mother was a pianist and music teacher. Not surprisingly, David’s older brothers and he became horsemen and musicians. By his late teens, David was playing piano professionally.

After graduating from the College of the Pacific in 1942, Brubeck enlisted in the U.S. Army. For two years, Private Brubeck played in an Army band in California. In 1944, he was trained to be a rifleman. Following D-Day, he was sent to northern France for combat service.

Luck then intervened. After hearing Brubeck playing piano with a Red Cross traveling show, his commanding officer ordered that he not be sent into combat. Instead, Brubeck and a few other soldiers, most of them decorated, formed a swing band that was trucked into combat areas to entertain troops. Called “The Wolf Pack,” it was the first racially-integrated band in the U.S. Army.

After Germany’s surrender in May 1945, Brubeck and his band mates were stationed in Nuremberg as part of the occupation army. They soon discovered the city’s Opera House and made it their rehearsal space.

On July 1, 1945, The Wolf Pack played in a United Service Organizations (“USO”) show that reopened Nuremberg’s Opera House. Later that summer and through the fall, Brubeck and his fellow soldier-band mates served, roamed, rehearsed, and performed, including in USO shows featuring sixteen members of the Radio City Music Hall Rockettes, in Allied-occupied Germany.

The Wolf Pack members were well aware of the IMT proceedings that began in November 1945 in Nuremberg’s Palace of Justice. Brubeck did not attend the trial but he interacted with U.S., U.S.S.R., U.K., and French personnel who were parts of it, including at meals in a large mess hall that they shared.

In January 1946, Brubeck returned to the United States and was honorably discharged from the Army.

He then became, well, Dave Brubeck. He lived a long, productive life of musical genius and international acclaim. Although his time ended physically on December 5, 2012, Dave Brubeck lives on in his compositions, in his recordings, in memories of those who got to see him play, and in the histories of his performance venues.

Across the years after 1945, Dave Brubeck never forgot World War II or Nuremberg. In winter 2004, for example, he recorded a musical autobiography, the leading songs of his war years. The album, “Private Brubeck Remembers,” contains twenty-four piano solos and, in CD editions with a bonus disk, a lengthy interview of Brubeck by Walter Cronkite. In the interview, they share memories of 1945 Nuremberg, where Cronkite also lived as he reported on the IMT trial for the United Press.

In 2005, the City of Nuremberg, noting Dave Brubeck’s dedication throughout his musical career to toleration, peace, and human rights and his personal history in Nuremberg, invited him to participate in the City’s commemoration of the 60th anniversary of the start of the IMT trial. Brubeck accepted—he and his band mates added Nuremberg on the front end of a concert tour that also took them to Austria, Switzerland, Spain, and Poland.

On November 16, 2005, the Dave Brubeck Quartet played in Nuremberg’s Schauspielhaus (playhouse). This modern venue is part of the Staatstheater (National Theater). This complex includes the historic Opera House—the same Opera House that The Wolf Pack helped to reopen to music, and that Justice Jackson then wisely declined to make a courtroom, in July 1945.

During Brubeck’s November 2005 visit to Nuremberg, the Lord Mayor thanked him “for liberating our City.” In fact, with his music, he did.

- For video excerpts from a 2009 Dave Brubeck interview about his World War II service and his time in Nuremberg, click here:

(Hat tip: Gregory L. Peterson)

- For video of Dave Brubeck explaining, in the same interview, what inspired him to compose his signature tune “Take Five,” click here:

- For video of a 1966 Dave Brubeck Quartet performance, in Berlin, Germany, of “Take Five,” click here: