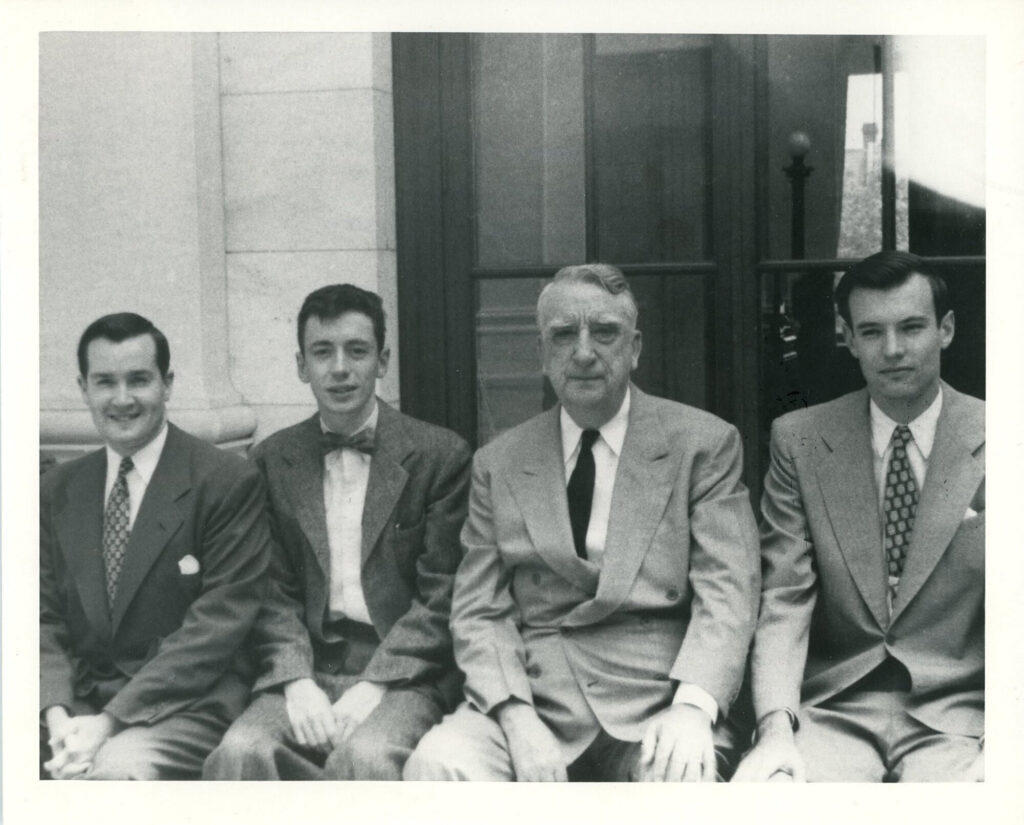

In May 1953, Justice Robert H. Jackson had lunch at the United States Supreme Court with that term’s law clerks. The group included Jackson’s own clerks William H. Rehnquist and Donald Cronson and the seventeen other men who were working for his eight fellow Justices.

This was in keeping with a Court tradition (which has continued). Each law clerk of course gets to know his or her justice, through their close working relationship, very well. And the law clerks also get to know the other Justices at a personal level, at least a little bit, through these conversation-filled, informal lunches.

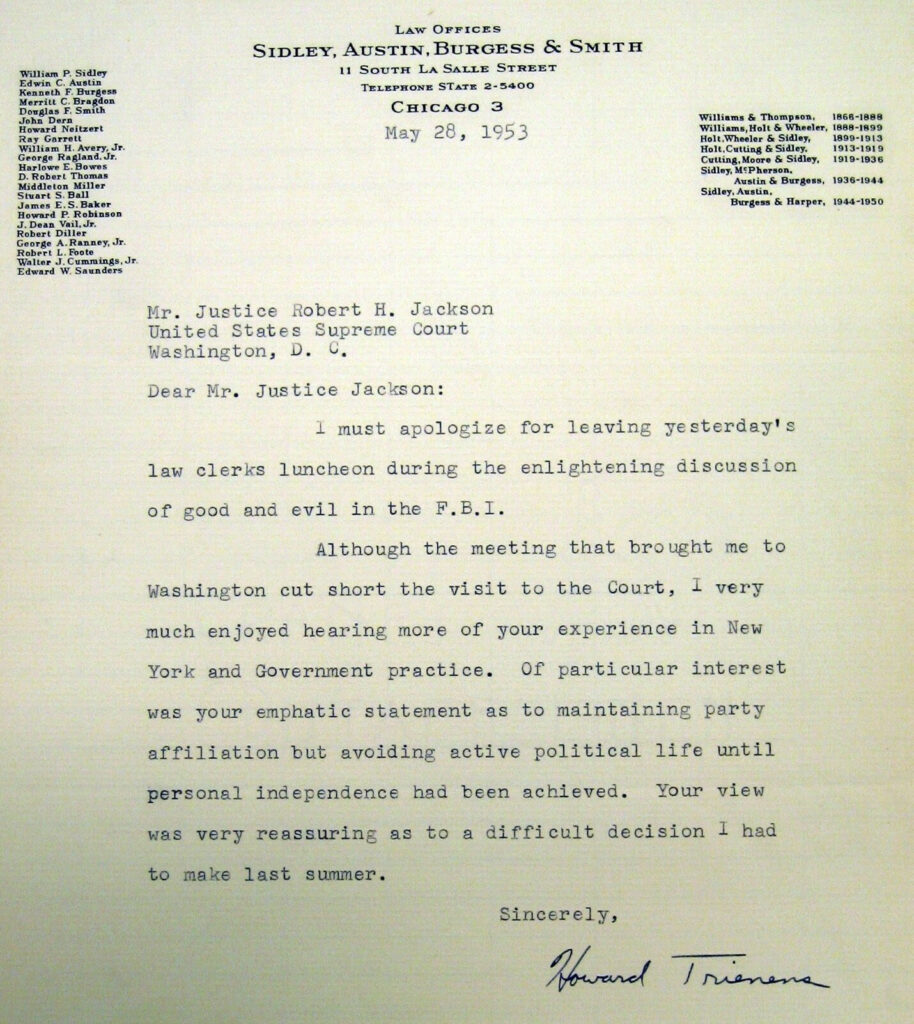

During this lunch, Justice Jackson told the clerks about his two decades (1913-1933) in private law practice in New York State. He also told them of his government service, including his five-plus years (1936-1941) in the U.S. Department of Justice. They discussed some of the good and some of the evil in the Department’s Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). And Jackson recommended strongly that these young lawyers, many interested to some degree in politics, follow his path: be a member of a political party, sure, but do not get actively involved in politics until you have achieved some personal, meaning professional and financial, independence.

One former Supreme Court law clerk joined the current clerks at this lunch with Justice Jackson. This man, Howard J. Trienens, had clerked for Chief Justice Vinson for two years, 1950-1952.

(L-R) Newton N. Minow, James C.N. Paul, and Howard Trienens.

When Trienens’s clerkship ended in summer 1952, he considered taking a job in politics. My guess is that it had something to do with Illinois governor Adlai Stevenson’s presidential campaign. Trienens agonized before deciding to turn it down. He decided instead to become a law firm associate in Chicago, his hometown.

A year later, Trienens was still wondering, at least as he traveled to Washington, D.C., on law firm business, if he had made the right decision. On that occasion, May 27, 1953, he stopped at the Supreme Court to visit, and he somehow became part of the law clerks’ lunch with Justice Jackson.

When Trienens heard Jackson say that young lawyers should not jump too soon into politics, Trienens took this as reassurance about his choice to practice law.

Howard Trienens in fact never left private law practice. He stayed at his firm, which today is known as Sidley. He became a giant in law and business, rose to be one of the firm’s leaders, and practiced there for almost seventy years. Sadly, he passed away this summer at age 97. I was acquainted with him, appreciated his kindness, and deeply admired his brilliance and his professionalism. For Sidley’s tribute page chronicling Howard Trienens’s life and career, click here.