Justice Robert H. Jackson spent Sunday, December 7, 1941, at Hickory Hill, his home in the rural countryside of McLean, Virginia. He spent the afternoon reading, with music on the radio in the background. He probably was reading legal briefs, preparing for a United States Supreme Court argument session that would commence the next day.

Eight miles away, at the White House, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s press secretary announced to reporters just before 2:30 p.m. that Japan had attacked Pearl Harbor and Manila. Justice Jackson soon learned the shocking news when an announcer interrupted the musical broadcast.

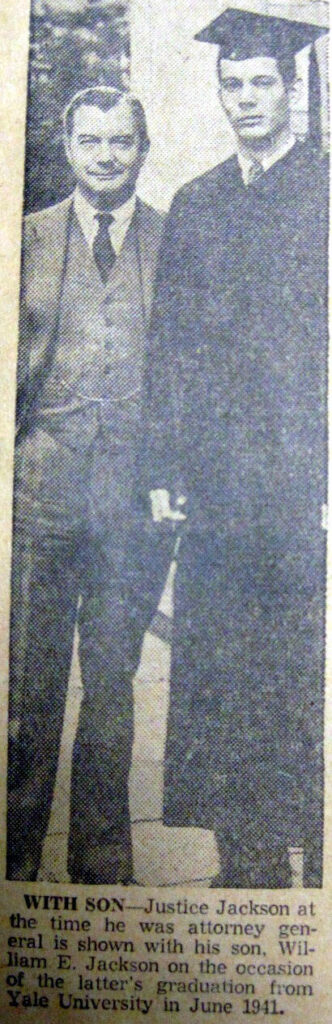

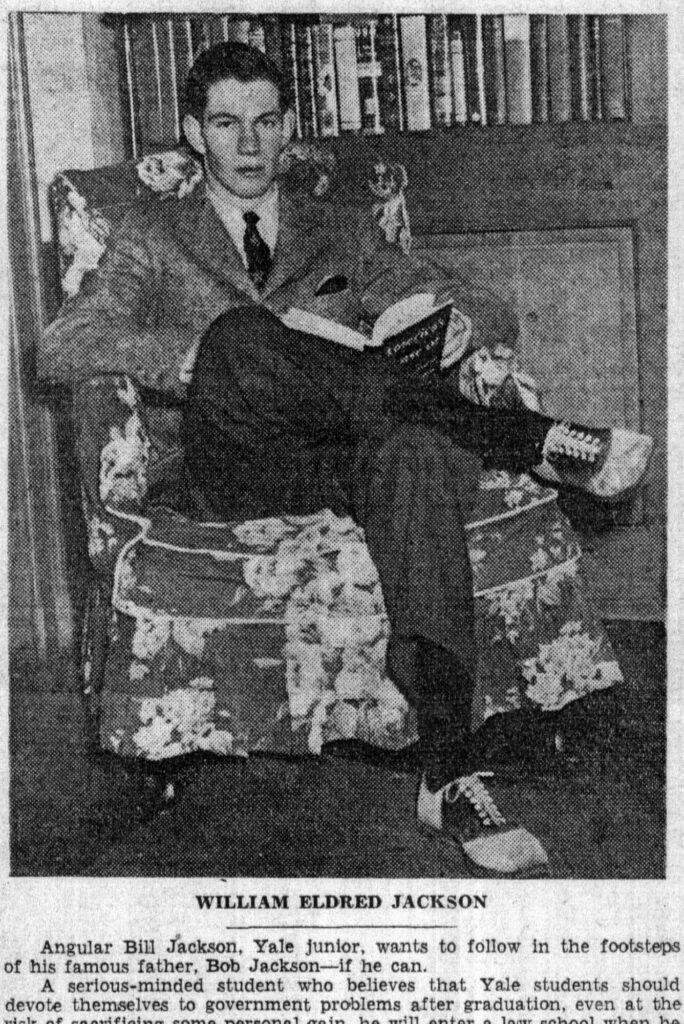

That evening, Robert Jackson and his wife Irene received a long-distance telephone call from their son William Eldred Jackson, age 22. He lived in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and was a law student at Harvard. He had graduated from Yale College six months earlier, in June 1941, with high honors.

Bill Jackson was an accomplished, very talented writer and college journalist. He considered, often and very seriously, pursuing a career in some kind of writing. In summer 1941, however, as U.S. Attorney General Robert Jackson was being appointed to the Supreme Court, Bill Jackson decided to apply to law school.

Bill Jackson arrived at Harvard Law School in September 1941. He worked diligently on his studies but remained unsure about whether law school and law practice were for him. He regarded his first year of law school as a no-commitment experiment.

He considered military service as one alternative to law school, but it was not an option. Bill had registered for the draft, but he then had flunked the Selective Service physical due to poor eyesight, a knee injury, and his lanky, underweight build.

But now, as of December 7, 1941, his country was at war. In his telephone call to his parents that Sunday evening, Bill proposed to drop out of law school immediately. He talked of seeking some kind of job that would be part of the war effort. The conversation was inconclusive.

The next morning, Justice Jackson drove from Hickory Hill to the Supreme Court. In his chambers, his secretary Ruth Sternberg typed this letter (which Jackson either dictated or, more likely, wrote or dictated in rough form and then edited into the final form he wanted and then sent):

Dear Bill:

Since your telephone call last evening I have meditated on your suggestion that you leave law school and get into the scrap at some more exciting point. I think I can appreciate your impatience because I, too, am removed from the excitement and hurry of executive place and, like yourself, am tied in with the slow processes of the law. I think you should hesitate a little, however, and think the matter over before you jump. One of the most difficult problems to deal with in excited days arises from the number of people who rush to offer themselves for service in which they would have no fitness except willingness. If I apprehend your talents aright, you have no particular adaptability to the ways of violence. You have been rejected on physical grounds, but my personal estimate is that you could be fitted much sooner physically than psychologically for war service.

In the second place, the value of what you are now doing: The only use of war is to re-establish equilibriums which permit people to live in peace. Unless I read the signs wrongly, the United States and her institutions will be under heavier strain in the distraught conditions that will follow this war than it will during the war. The Japanese attack, stupidly conceived, has accomplished no military objective for Japan and has completely unified the American people, as well as stimulated them for a maximum effort. That we will carry on successfully, I have no doubt. It will be different when the conflict is over, when men must be demobilized and jobs are scarce, when the sustaining influence of an external danger is relieved and recriminations and accusations begin. It is in those days that I think you might have a mission, provided you are prepared, with a thorough knowledge of institutions as they are and the principles on which society has been functioning.

A people is as stupid as a man to lose its soul in gaining a world. The philosophy of the law and the culture of the democratic order comes close to being the soul of the American people, and the services rendered to it are undramatic, but timeless.

This morning I feel that the treacherous Japs have invited the fate of Carthage and we ought to see it administered. Nevertheless, there lurks a question as to how far we vindicate civilization by such vindictive methods. Unfortunately, we have no machinery by which the really guilty can be reached.

My own hunch is that there is a much more important front on which men of your temperament and mine can battle than the front of war. That is the front of organizing a peace so that it will stay peaceful, and I suspect that you will do your race as much good if you devote the next two and a half years to preparation for that as you would do by abandoning the thing for which I think you have some special fitness to go into fields in which the Selective Service has already adjudged you not adapted. Of course, whatever you decide to do will have all we can give it.

Looking forward to seeing you soon.

[/s/ Love, Dad]

At noon on that December 8, eighty years ago today, Justice Jackson and his Supreme Court colleagues took the bench for their scheduled session. They granted motions to admit thirty-two lawyers, assembled there, to practice before the Court. Then, immediately, the Court recessed.

The Justices left the Court building, crossed First Street, N.E., entered the U.S. Capitol, and attended a joint session of Congress. They heard President Roosevelt identify December 7, 1941, as “a date which will live in infamy.” They heard the President ask Congress to declare that the United States was at war with Japan.

At 2:30 p.m., the Justices returned to their bench. They announced decisions and heard the start of an oral argument before recessing in late afternoon.

* * *

Bill Jackson remained at Harvard Law School, graduating in February 1944. Then he joined the U.S. Navy and began to work as a lawyer in the Bureau of Ships in Washington.

In April 1945, as the Allies were about to win victory in the European Theater of World War II, President Truman appointed Justice Jackson to serve as U.S. Chief of Counsel for the prosecution of Nazi war criminals. Robert Jackson then hired his son Bill to serve as his executive assistant.

The Jacksons together then undertook the work that Justice Jackson had envisioned, somewhat uncannily, in the hours immediately after Pearl Harbor.

In 1945 and 1946, in London and then in Nuremberg, cities that were important parts of “the front of organizing a peace so that it will stay peaceful,” the Jacksons, working with many colleagues, helped to build legal machinery to reach the “really guilty,” and thus to vindicate civilization.