In October 1948, Justice Robert H. Jackson read a Washington newspaper story about the then-ongoing project to build a new United States Courthouse in the District of Columbia, on the site of a parking lot south of the District’s Municipal Center.

Justice Jackson thought immediately of a courthouse-building project that he had been part of—in an official sense, he had led it—seven years earlier. In summer 1945, Jackson, serving as U.S. Chief of Counsel for the Prosecution of Axis War Criminals in the European Theater, had negotiated with allied nation representatives to create the world’s first international criminal court. One of the many issues that Jackson worked on was where this court—this forum for an international trial of Nazi war criminals—should be located. At the recommendation of the U.S. Army, Jackson favored the city of Nuremberg, located in the U.S. occupation zone of what had been Nazi Germany.

Jackson visited Nuremberg in early July 1945. He inspected its courthouse, the Palace of Justice, which was connected to a large prison. The buildings were war-damaged but repairable. Jackson decided that this should be the trial venue.

A couple of weeks later, Jackson showed the Palace of Justice to his British and French counterparts. They agreed that it should be the trial site. And their Russian allies soon made the agreement unanimous—the four-nation trial of the principal surviving Nazi leaders would occur in Nuremberg’s Palace of Justice.

The ensuing project of repairing and preparing the Palace of Justice for trial was managed by U.S. Army Captain Daniel Urban Kiley, a thirty-three-year-old architect from Boston who had served during World War II in the U.S. Office of Strategic Services.

Dan Kiley redesigned the Palace of Justice’s largest courtroom, Courtroom 600. In consultation with Justice Jackson and others, Kiley planned a courtroom that would center on the witness box, located in the front-center of the room. The defendants’ box and their lawyers’ tables would be in front of the witness, to the right. The judicial bench and tables for court staff would be in front of the witness, to the left. The witness would face the questioner’s podium and, behind that, five tables of prosecutors. Behind them and in a balcony would be seats for spectators, including a large press corps. The front corner of the courtroom would have a soundproof box for interpreters. Boxes for cameramen would be built into the walls of the courtroom.

As part of planning these modifications, Kiley’s team built an architectural model showing how Courtroom 600 would look.

They then, assisted by German prisoner of war labor, did the construction work.

The courtroom was completed in time for the trial to commence on November 20, 1945. It all worked well enough during the ten-month trial that followed.

Justice Jackson returned to the U.S. and his job as a Supreme Court associate justice in October 1946.

Other U.S. lawyers, led by Jackson’s former deputy Telford Taylor, who had been promoted to the rank of Army brigadier general and appointed by President Truman to succeed Jackson as U.S. chief of counsel, remained in Nuremberg. During the next two-plus years, from Fall 1946 until Spring 1949, Taylor and his team prosecuted in Courtroom 600 twelve additional cases against Nazi war criminals—the U.S. “subsequent proceedings.”

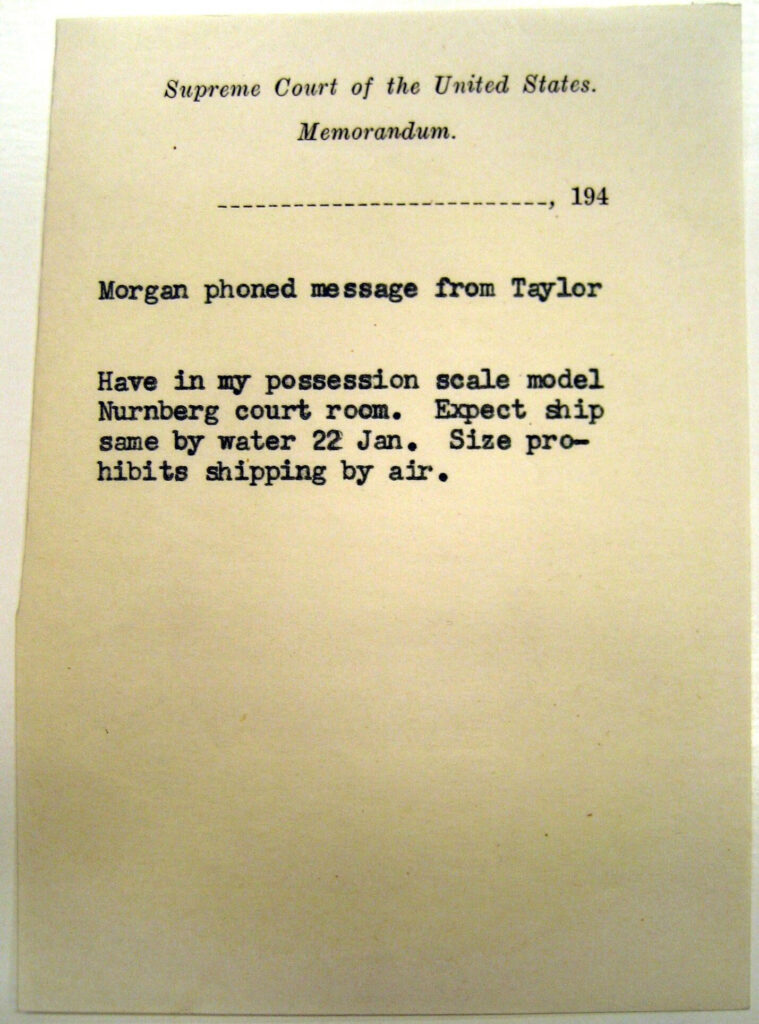

In late 1946, it seems, Telford Taylor in Nuremberg informed his office in the Pentagon that he soon would be shipping to Justice Jackson the architectural model of Courtroom 600. The Pentagon office director telephoned that message to Jackson’s secretary at the Court. She typed up the message and gave it to him.

And then, in October 1948, Justice Jackson read of the plans to build Washington, D.C.’s new federal courthouse.

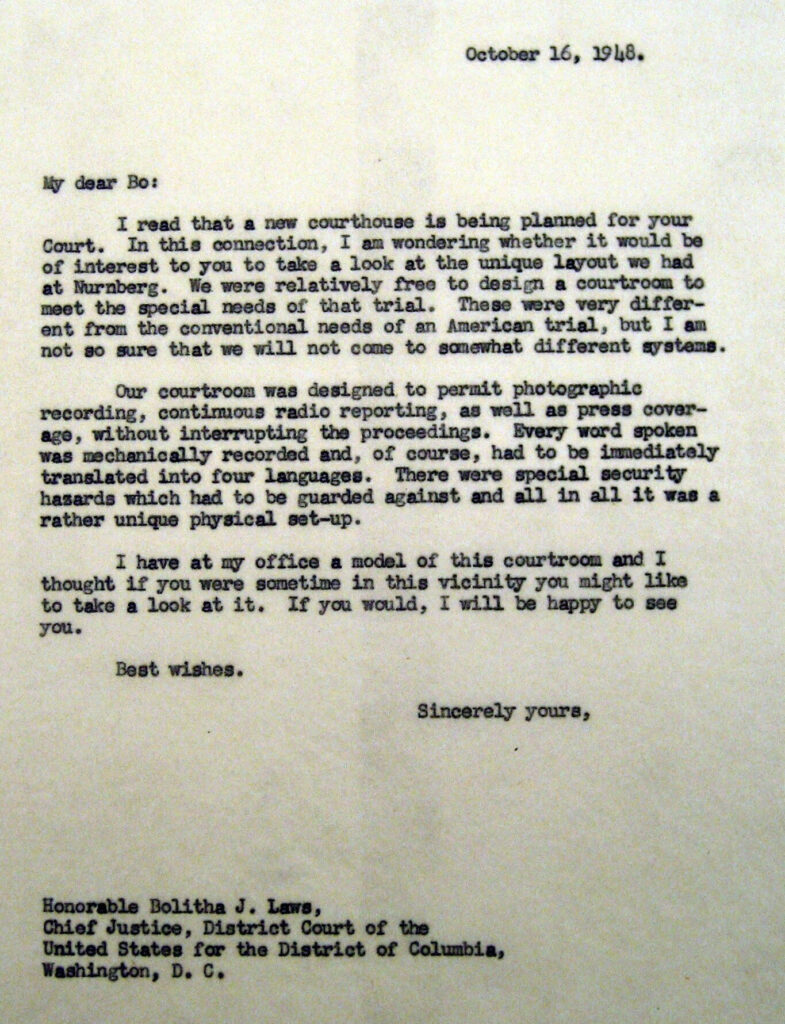

Jackson, thinking of and probably looking at his Nuremberg model, wrote on October 16 to his friend Chief Justice Bolitha Laws of the District Court of the U.S. for the District of Columbia. Justice Jackson told Chief Justice Laws of the Nuremberg model and the unusual features that Dan Kiley and team had built into Courtroom 600 in 1945. Jackson invited Laws to come to his chambers to see the model.

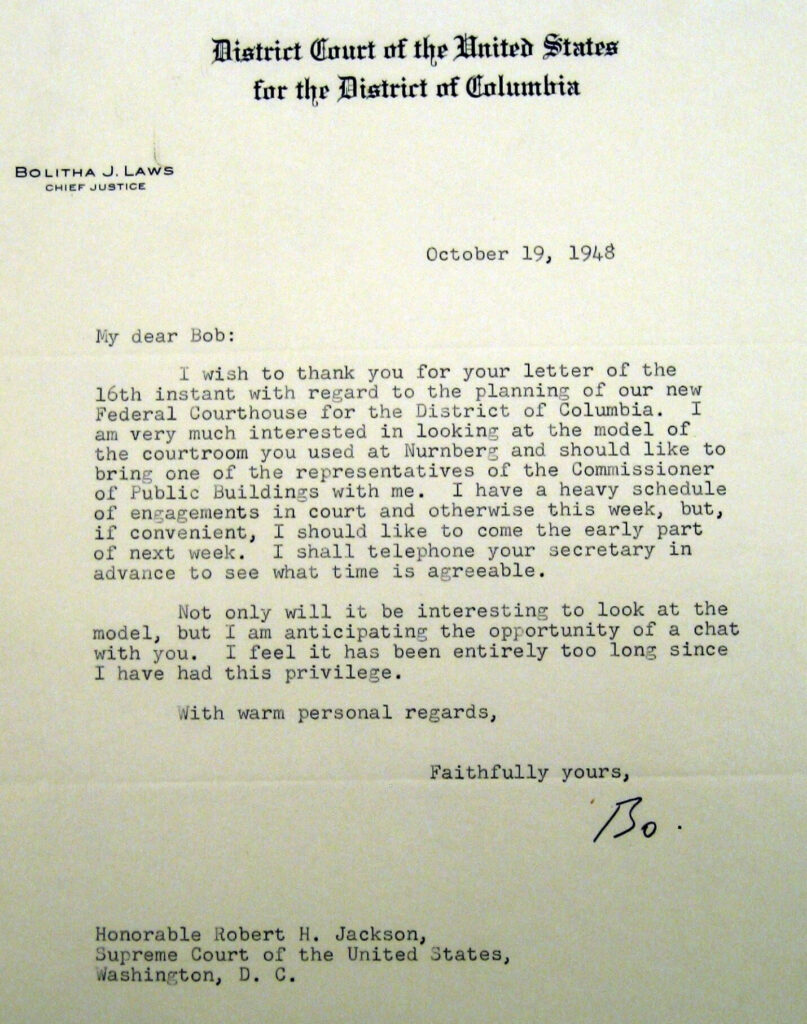

Chief Justice Laws visited Justice Jackson at the Supreme Court on October 26, 1948. They met in Jackson’s chambers. Laws looked with interest at Jackson’s model of Nuremberg Courtroom 600…

The trail from there is cold.

The new D.C. federal courthouse got built. It today is the E. Barrett Prettyman U.S. Courthouse. Its courtrooms are U.S.-traditional, featuring the judicial bench in the center-front of the room. They do not match Jackson’s and Kiley’s 1945 Nuremberg Courtroom 600.

Yes, Nuremberg today is a powerful law and government model–our world continues, sadly, to see military aggression, war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide, and Nuremberg is a leading model for our work to hold perpetrators legally accountable for those crimes.

But Nuremberg also was, physically, in Justice Robert Jackson’s chambers in October 1948, an architectural model for study and learning

I hope that this model of Nuremberg’s Palace of Justice Courtroom 600 still exists. It is not, so far as I have found, at the U.S. Supreme Court or in the possession of a Jackson descendant.

So this Jackson List post is, in the end, a crowd-sourced request: If you find what once was Justice Jackson’s Nuremberg model, please let me know.

I then will do what I can to get it preserved, conserved, and displayed properly.