From June through August 1945, United State Supreme Court Justice Robert H. Jackson, President Truman’s appointee to serve as U.S. Chief of Counsel for the prosecution of the leading Nazi war criminals, negotiated in London with his British, Soviet, and French counterparts. On August 8, they signed the historic London Agreement that created the International Military Tribunal and a Charter defining its procedures. Justice Jackson then flew home for a week of consultations, including with President Truman.

Jackson left his London Conference principal deputy Sidney S. Alderman, a lawyer who was on leave from his Washington job as general counsel of the Southern Railway Company, in charge of the London staff. The personnel worked on evidence-gathering and analysis, interrogations, legal analyses, and early drafts of what would become, in October, the Nuremberg indictment.

Alderman also supervised some moments of staff recreation. On Sunday, September 2, 1945, for example, he and three colleagues took the day off. These fellow lawyers were Francis M. Shea, until recently the Assistant Attorney General heading the Claims [today the Civil] Division in the U.S. Department of Justice; Col. Telford Taylor, U.S. Army, a former New Deal agency lawyer; and Lt. (j.g.) Bernard D. Meltzer, U.S. Navy, another former young government lawyer in Washington

Alderman, Shea, Taylor, and Meltzer had lunch that day in the Officers Mess in the Grosvenor House hotel on Hyde Park. A reporter, Henry T. Russell of the New York Herald-Tribune, joined them. After lunch, the five squeezed into a four-person car and drove about eight miles from central London to Wimbledon’s All England Lawn Tennis and Croquet Club.

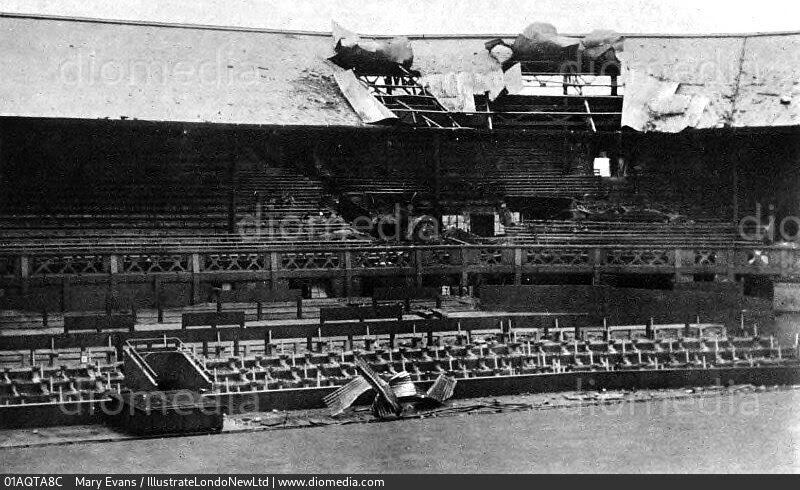

The Wimbledon championship tournament had been suspended since 1940. The Club, including its Centre Court viewing stands, had been severely damaged by German bombing during the war.

But Centre Court itself was undamaged. And so while Alderman watched, the others played doubles. Frank Shea picked Henry Russell, a very good player, as his partner. They defeated Tel Taylor and Bernie Meltzer in three straight, very close sets. After the match, the players and Alderman had tea with bread, butter, and jam.

On the drive back into London, Meltzer, the smallest, sat on Alderman’s lap.

At the U.S. Officers Club, they had drinks and maybe some food. Shea, Meltzer, and Russell then retired for the evening. Alderman and Taylor, accomplished and passionate musicians, stayed on, talking at length about music.

Work resumed the next day.

Jackson returned from Washington a week later.

He and staff then decamped from London to Nuremberg, where they lived, worked, and prosecuted for the next year in, if you will, a center court of justice and history.

During his year in Nuremberg, Robert Jackson worked intensely.

Maybe he also played a little tennis. The house that he occupied outside Nuremberg—which Taylor subsequently occupied after Jackson returned to the U.S. in 1946 (the year the Wimbledon tournament resumed)—had its own court.