When President Franklin D. Roosevelt took office in 1933, he nominated, and the Senate immediately confirmed, William H. Woodin, a Republican businessman and political supporter, to serve as United States Secretary of the Treasury. Secretary Woodin then worked on the U.S. “Bank Holiday,” the enactment of bank deposit insurance, the U.S. move to leave the gold standard, and many other policies that sought to mitigate the Great Depression.

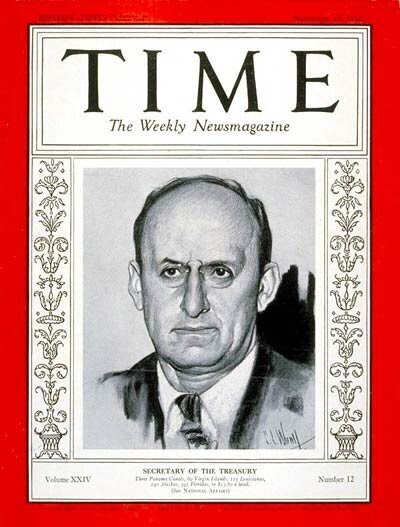

But Secretary Woodin was not in strong health. He resigned at the end of 1933. President Roosevelt then nominated, and the Senate confirmed, Henry Morgenthau, Jr., FDR’s New York State neighbor and friend, to succeed Woodin.

Secretary Morgenthau, taking office in January 1934, decided immediately to change some Treasury Department senior personnel. He focused on one of Treasury’s major components, the Bureau of Internal Revenue. The Bureau was charged by law with raising all U.S. government monies, including from income, estate, excise, liquor, gift, customs, and other miscellaneous taxes. Revenue’s General Counsel interpreted tax laws and handled government controversies with taxpayers, including a large volume of litigation before the Board of Tax Appeals, in U.S. circuit courts of appeals, and before the U.S. Supreme Court.

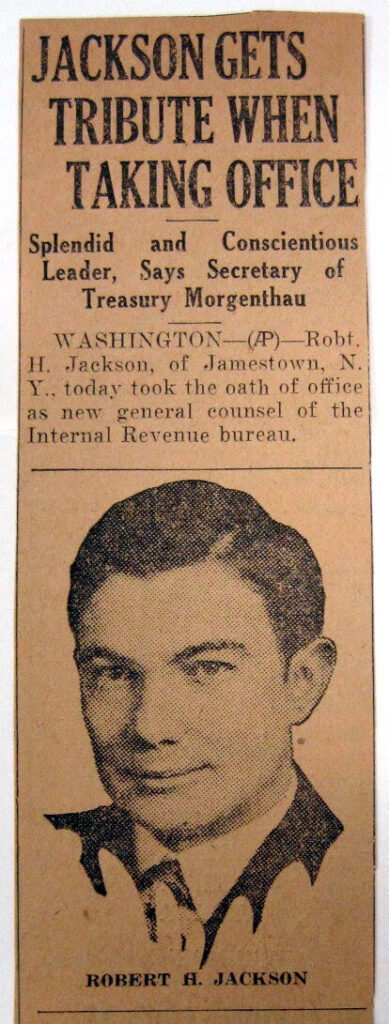

Morgenthau decided that he would replace Revenue’s General Counsel, Maryland lawyer E. Barrett Prettyman, Sr., with Robert H. Jackson of Jamestown, New York.

Robert Jackson, then age forty-one, was a leading, well-regarded lawyer in New York State and nationally. He was somewhat active in Democratic politics in New York. He was known to President Roosevelt—they had been acquainted for more than twenty years, and Jackson had been an FDR supporter in his 1928 and 1930 gubernatorial campaigns and then his 1932 presidential campaign (each successful). Morgenthau, along with others inside the Roosevelt administration, was acquainted with Jackson. Morgenthau knew of Jackson’s high reputation as a lawyer and his skills as a Roosevelt campaigner.

President Roosevelt thus nominated Robert Jackson to become one of the Treasury Department’s Assistant General Counsel, the General Counsel in the Department’s Bureau of Internal Revenue. Jackson was not a tax law specialist, but he was attracted by the action of “New Deal” Washington, by the opportunity to do public service, and by the significance of the Revenue job.

In February 1934, the Senate confirmed Jackson’s nomination. He moved with his family to Washington, to a hotel apartment. He left his Jamestown law practice in the hands of his partner and associates. He expected to return to private life within months.

As General Counsel heading the Bureau of Internal Revenue, Robert H. Jackson was responsible for running the largest law office on, well, Earth. The office had, under the General Counsel, four assistant general counsel, 260 attorneys, and a large staff of other employees. It was bigger than the U.S. Department of Justice in Washington, for example, and bigger than any private law firm.

Jackson’s appointment to serve as General Counsel in Revenue was the first of his five nominations by President Roosevelt and confirmations by the Senate to high office. The others: in the U.S. Department of Justice, Assistant Attorney General, then Solicitor General, and then Attorney General; and in the U.S. judiciary, associate justice of the Supreme Court.

Plus FDR detailed Jackson in 1935 from Treasury to the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

Plus the U.S. Attorney General in 1937 reassigned Assistant Attorney General Jackson from heading DOJ’s Tax Division to heading DOJ’s Antitrust Division.

Plus President Truman in 1945 appointed Justice Jackson to serve as U.S. Chief of Counsel for the Prosecution of Axis War Criminals in the European Theater—U.S. chief prosecutor at Nuremberg of the principal Nazi war criminals.

In other words. beginning in early 1934, Robert H. Jackson was in public service for the remaining twenty years of his life.

Credit to Morgenthau, Roosevelt, and others for spotting what he had to offer, and also to Jackson for, again and again, stepping up.

Oh, and after meeting in somewhat awkward 1934 circumstances—Morgenthau replacing Woodin’s person with his own—Robert Jackson and Barrett Prettyman became close, lifelong friends.