Until 1933, the United States government minted gold coins. And the U.S. issued paper currency that included certificates redeemable in gold bullion held in government repositories. The U.S. was, in other words, on “the gold standard”—the U.S. dollar was tied to the market value of that commodity.

By early 1933, in the depths of the Great Depression, this system was at risk of collapse. The amount of U.S. currency that was in circulation plus the book value of bank deposits outstripped significantly the government’s gold reserves.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt acted on March 6, 1933, his third day in office, to address this crisis. He began the process of taking the U.S. off the gold standard.

President Roosevelt acted first under a wartime measure that still was on the books, the 1917 Trading With The Enemy Act. He issued an order prohibiting U.S. banks from paying out or conducting any international transaction in gold.

Just days later, President Roosevelt obtained new legislation so that he could continue this project domestically. Congress passed and the President signed the Emergency Banking Act of 1933. As this law authorized, the Treasury Department then nationalized gold—it required all persons to surrender to the government their gold coin, bullion, and certificates, in exchange for paper dollars. As the law also authorized, the government formally devalued the dollar. This caused domestic prices to rise, increasing the incomes of struggling farmers and other producers of domestic materials and goods.

Later, Congress nullified so-called “gold clauses,” the provisions in contracts that entitled obligees to be paid in U.S. gold coin.

And acting pursuant to the Gold Reserve Act of 1934, the Roosevelt administration further devalued the dollar and removed gold coins from circulation.

These measures helped to stimulate economic recovery.

They also prompted high profile litigation—private economic interests challenged the legality of these government actions. Gold certificate-holders challenged the Treasury’s power to compel them to surrender certificates in exchange for currency, not gold. Government bondholders challenged the government canceling bond provisions that entitled them to repayment in gold. Contract obligees challenged Congress nullifying contractual gold clauses.

* * *

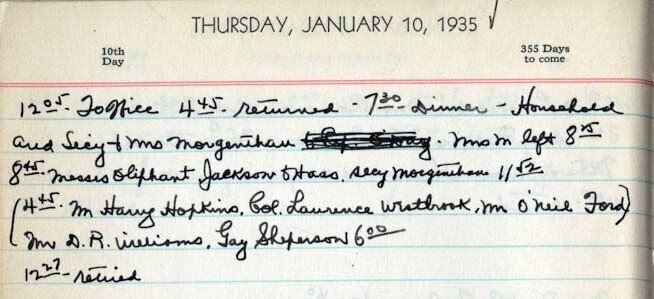

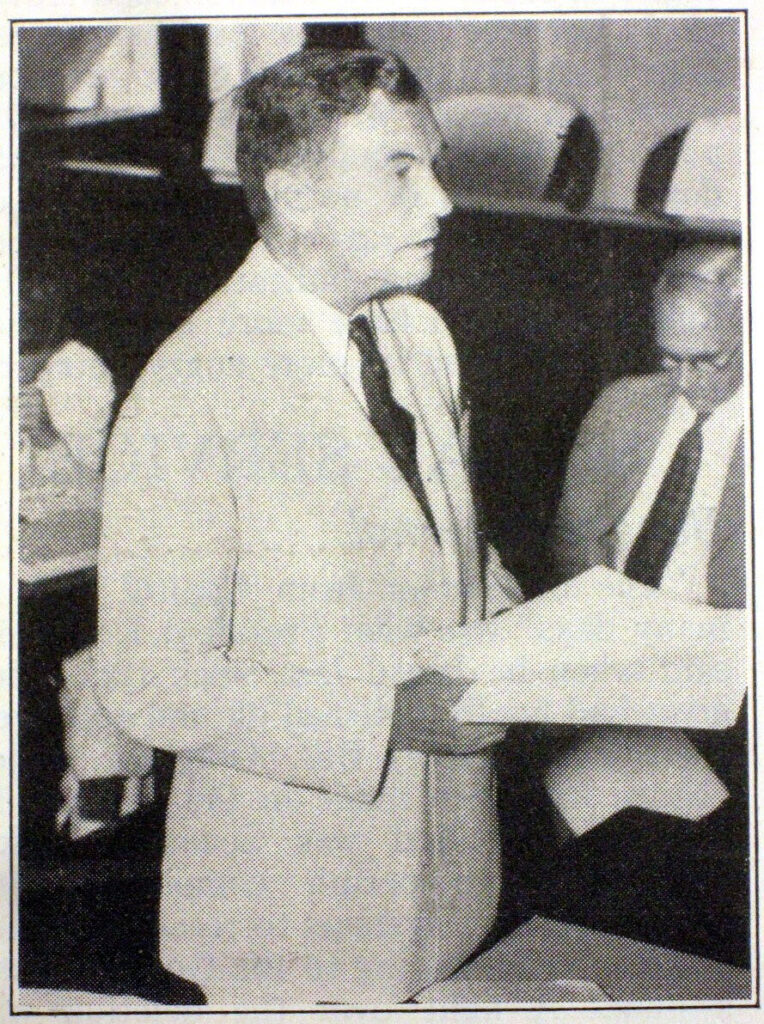

On Thursday, January 10, 1935, President Roosevelt had a long evening meeting in the White House residence with senior Treasury Department officials. They were Treasury secretary Henry Morgenthau, Jr., his general counsel Herman Oliphant, Treasury economist George Haas, and the counsel heading Treasury’s Bureau of Internal Revenue, Robert H. Jackson.

President Roosevelt and these aides discussed the message about tax law enforcement and reform that he was preparing to send to Congress.

They also discussed the “Gold Clause Cases,” which that week were in the midst of being argued before the U.S. Supreme Court.

They noted that Supreme Court Justices were being very tough in their questioning of the government’s lead advocate, U.S. Attorney General Homer S. Cummings. As Jackson recalled it later, President Roosevelt said that this questioning suggested that the Court might hold his devaluation policy to be unconstitutional, which would increase government obligations to bondholders. Secretary Morgenthau said that he too was very concerned.

According to Jackson, President Roosevelt asked Morgenthau what could be done to protect the government against the chaos that would result from an adverse Court decision. The President said that he could not accept an adverse decision.

They discussed options. “Outright defiance of the Court was possible,” Jackson wrote (in the passive voice, without saying that this was stated explicitly or, if it was, by whom or how seriously).

They discussed possibly “packing” (enlarging) the Court to produce a new majority that would uphold the laws and policies that were at issue.

Jackson told the group that he recently had read a political science journal article about President Ulysses S. Grant’s two 1870 Supreme Court appointments that had enlarged the Court. These new justices had become part of a new Court majority that, as Grant wanted, upheld the constitutionality of paper money. As the new, larger Court made that decision, it had overruled a recent decision, adverse to Grant’s position, by the previous, smaller Court.

President Roosevelt’s January 10, 1935, meeting with Morgenthau, Oliphant, Jackson, and Haas adjourned just before midnight.

In the days ahead, the President and advisers, including Robert Jackson, continued to consider privately their legal options in the event that the Supreme Court decided the Gold Clause Cases against the President and Congress.

That did not come to pass.

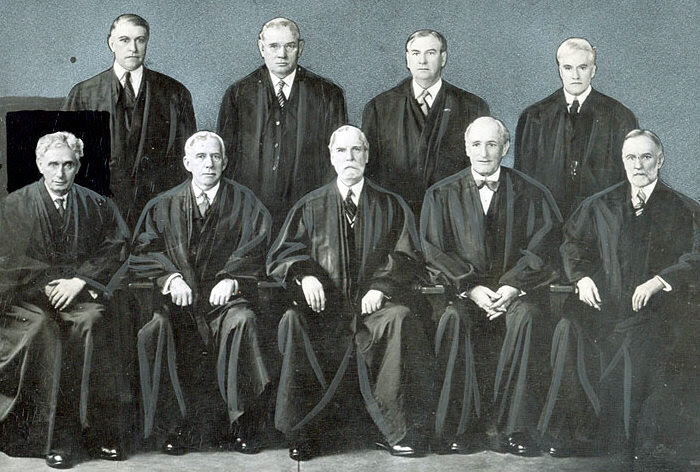

On February 18, 1935, the Supreme Court, by a 5-4 vote, decided these cases in the government’s favor.

(International news service photograph)