In June 1945, Owen J. Roberts, an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, left Washington before the Court had finished its term and begun its summer recess. He went home “early” to his farm in Chester Springs, Pennsylvania, west of Philadelphia.

Justice Roberts then quit the Supreme Court. He had been a justice for fifteen years. He had turned age 70 a month earlier. He was eligible for a full federal judicial pension. And he was sick of being on the Court—although Justice Roberts admired and was close to some of his Court colleagues, such as Justices Felix Frankfurter and Robert H. Jackson, Roberts was estranged from some of the other justices for various reasons, including because he thought that they sometimes behaved unethically and judged politically.

On June 30, Justice Roberts sent his resignation letter—not retirement into senior judicial status; resignation—to President Harry S. Truman. Roberts also wrote to Chief Justice Harlan Fiske Stone, to alert him. Roberts informed the Chief Justice that the White House would announce Roberts’s resignation, and that Stone should keep the information confidential until then.

During summer 1945, President Truman did not move immediately to fill the new Supreme Court vacancy. The president, who had inherited the office when President Franklin D. Roosevelt died three months earlier, was occupied with higher priorities, such as the World War II Allied nations’ occupation of defeated and surrendered Germany; their policies regarding liberated Europe (which Truman traveled to—to Potsdam, in July—to discuss these matters with Stalin, Churchill, and Attlee); deciding to drop atomic bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki; Japan’s subsequent surrender, ending World War II fighting in the Pacific; and many domestic economic issues.

In mid-September 1945, President Truman finally acted to nominate a new justice. On Monday, September 17, he called U.S. Senator Harold H. Burton (R.-Ohio) at his Senate office. They had been Senate colleagues and friends—they called each other, still, “Harold” and “Harry.” The president invited Burton to come immediately to the White House.

They met upstairs in the President’s study. President Truman offered Senator Burton nomination to the vacant Supreme Court seat. Truman said that although Burton had been his first thought of who to nominate, the president’s thinking had moved for a time to other possibilities, including current or former federal circuit court judges (and all Republicans by political background) John J. Parker, Orie L. Phillips, and Robert P. Patterson. Truman said that he in fact had offered the position to Patterson, the Undersecretary of War. But Truman explained that he then had pulled this offer back because he needed Patterson to stay in the War Department; Truman soon would be nominating Patterson to become Secretary of War when the incumbent, Henry L. Stimson, retired.

Senator Burton replied to President Truman’s offer of a Supreme Court nomination by saying, “I would not ask for it.” Truman replied, “I know that. I would not appoint you if you did. But I will appoint you if you will take it.” Truman explained his objective: “I just want someone who will do a thoroughly judicial job and not legislate. I know that you will do that because we have talked about it.”

On September 18, President Truman announced his nomination of Senator Burton to serve on the Supreme Court. Truman sent the nomination to the Senate. It referred it to the Judiciary Committee.

Harold Burton was well-qualified by education, law practice, and public life experiences to serve on the Supreme Court. After graduating from Bowdoin College (1909) and Harvard Law School (1912), he had begun to practice law in the west, in Cincinnati. He then moved farther west, practicing energy and railroad law in Utah and then in Idaho. Burton then served as a U.S. Army lieutenant in the Great War (1917-1919). Then he settled in Cleveland, where he practiced law, taught law, became a state legislator, and served as the city’s attorney. He was elected mayor of Cleveland, serving from 1935 through 1940, when he was elected by Ohio voters to serve as a U.S. Senator.

On Friday, September 19, 1945, the Senate Judiciary Committee recommended that the full Senate suspend its rules and confirm President Truman’s nomination of Senator Burton.

That afternoon, eighty years ago today, the Senate did so, unanimously.

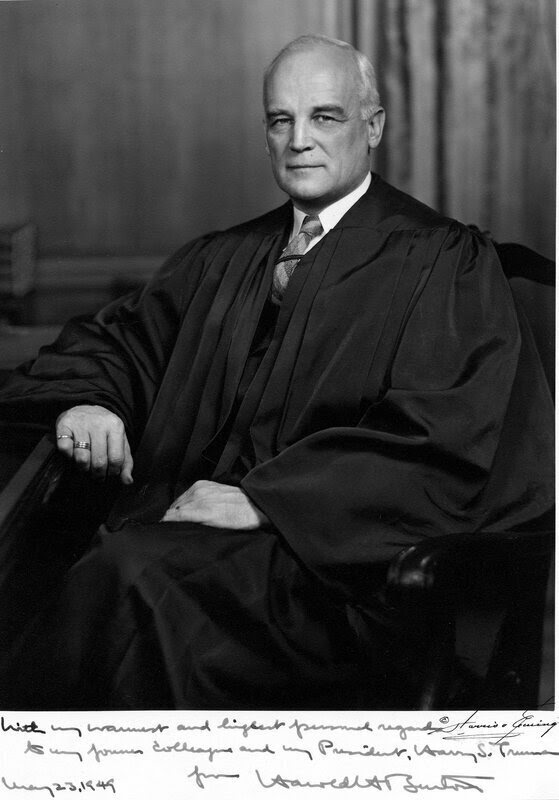

Harold Hitz Burton, age 57, was commissioned as a Supreme Court associate justice on September 22, 1945.

Justice Burton served in active status on the Supreme Court until October 1958. Health issues caused him then to retire into senior status. He remained a justice in senior status until his death in 1964.

Among scholars who study Justice Burton and the Supreme Court, he is regarded as a fine person who was a diligent, honest, extremely fair judge. He did not write many opinions, or famous opinions, or write beautifully, or cast many “deciding” votes. He did write, and he left to history, excellent, reliable notes of the Court’s conferences. He also kept, and he left to history, a very fine, factual, interesting, daily diary.

Those things are, in themselves, high forms of Supreme Court service.