At the United States Supreme Court, new law clerks tend to begin their employment in summertime, when the Court is in recess. The Justices vary as employers, but each generally assigns new law clerks to review, summarize, and make recommendations regarding petitions from litigants who lost in lower courts and now want the Supreme Court to take and decide their cases. The petitions are numerous. Each is connected to a voluminous record of briefs, transcripts, and decisions in courts below. The legal questions are complicated. The work is high stakes. It also, often, is boring. It demands a high level of law clerk discipline.

On the first Monday in every October, the Court begins a new term. The Justices announce decisions, mostly denials, on hundreds of petitions seeking review. The Justices begin to hear oral arguments in the cases that they have agreed to decide. By “First Monday,” some of the law clerks, and also some of the Court’s permanent personnel, such as secretaries and assistants to the Justices, are already worn down by the push to start the new term. And there is much, much work ahead.

In 1951, by the time that year’s new Court term was starting (on Monday, October 1), Justice Robert H. Jackson’s secretary Elsie Douglas observed how weary the law clerks, not to mention the secretaries, were.

This might have been particularly true of Justice Jackson’s own law clerk, C. George Niebank, Jr. He had worked for Jackson as part of a pair of law clerks during the previous term (1950-1951). During that year, Niebank accepted Jackson’s request to stay on for a second year as his sole law clerk. Thus starting in Summer 1951, Niebank was one law clerk doing what had been the work of two.

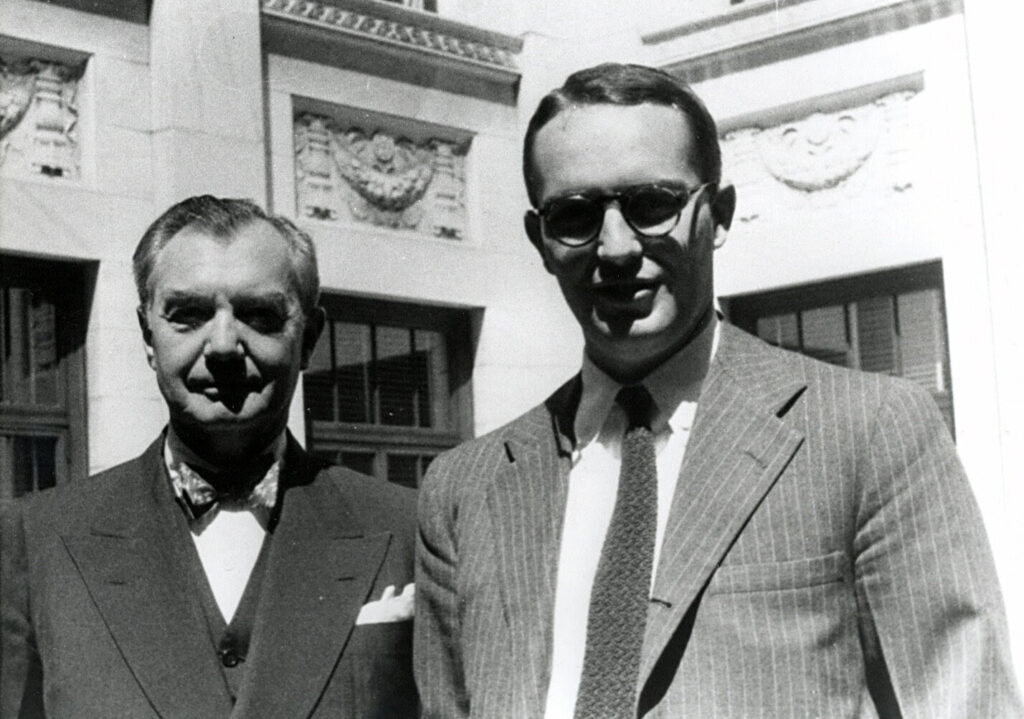

in a courtyard at the Supreme Court. (Photograph by C. Sam Daniels.)

So as that October Term 1951 began, Mrs. Douglas, no doubt having first gotten Justice Jackson’s approval, telephoned (she was extension 245) to every other Justice’s chambers. She invited all the secretaries and law clerks to a party in Jackson’s chambers (room 138).

The party occurred on Thursday, October 4, 1951. Perhaps Jackson was present.

Many law clerks were there. One was C. Sam Daniels, a University of North Carolina and Columbia Law School graduate who was clerking for Justice Hugo L. Black.

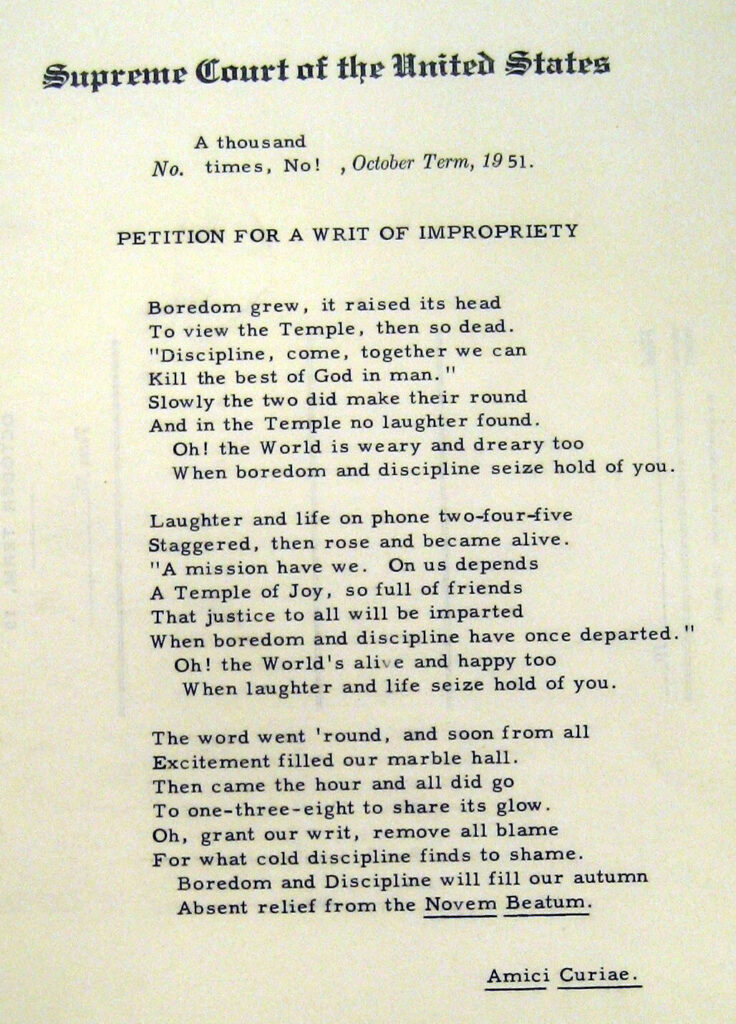

At the party, Sam Daniels read, or perhaps he just handed around on paper, a unique, humorous “petition.” He had drafted it, and then he had gotten it printed formally in the Court’s Print Shop. It had the form of a case (“No. __”) document that was being circulated among the Justices for review and decision. The petition sought, in effect, permission for the fun that the group was in the process of having on October 4, 1951. Maybe it was a document at-the-ready, to use later with any Justice who learned of the party and objected.

Mrs. Douglas, at least, was a supporter of Daniels’s petition. Of course she was—it was her party.

Ever organized, she kept a copy of the document in Jackson’s office files.