In Lake County, Florida, a circuit court judge yesterday granted a prosecutor’s motion to dismiss, based on prosecutorial misconduct and falsified evidence, criminal indictments against two men and to vacate the criminal convictions and sentences imposed on two others.

These criminal cases date back to 1949. The men, all now deceased, were Charles Greenlee, Walter Irvin, Samuel Shepherd, and Ernest Thomas. Each was African-American. In summer 1949, they were accused of abducting and raping a white woman. The men came to be known as “the Groveland Four.”

In the Groveland case, Florida’s legal system engaged in violent, illegal, racist torture and murder. Mr. Thomas was murdered by a mob. Mr. Greenlee, Mr. Irvin, and Mr. Shepherd were convicted by an all-white jury. After Irvin and Shepherd won a United States Supreme Court decision granting them new trials, Shepherd was shot and killed by the local sheriff, who claimed that he had stopped Shepherd from escaping. The sheriff also shot Irvin, but he survived. He then was retried, convicted, and served almost twenty years in prison. Greenlee also served about fifteen years in prison.

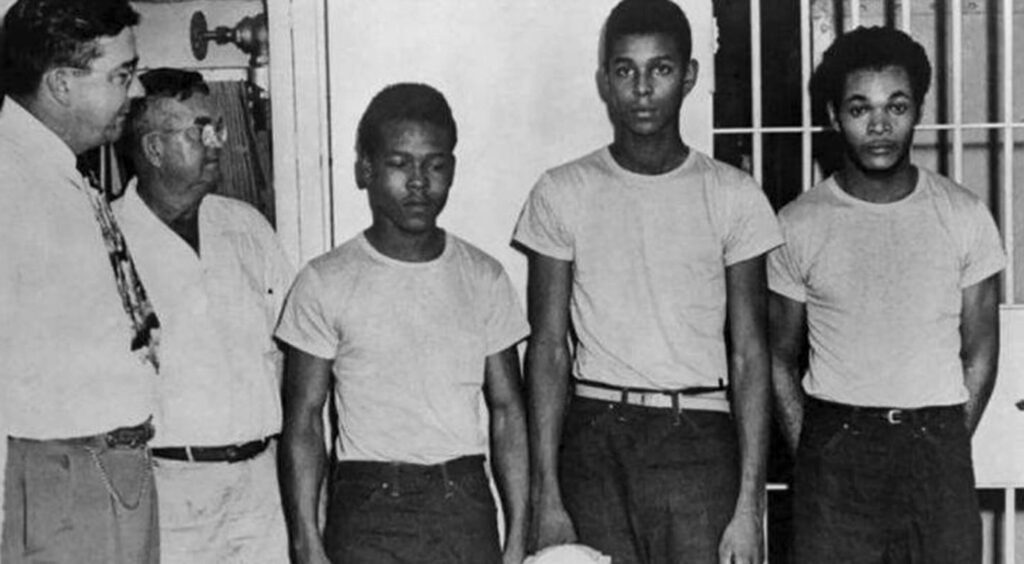

Samuel Shepherd; and Charles Greenlee (Florida State Library and Archives, via AP)

The U.S. Supreme Court decision in the Groveland case, rendered in the middle of the murderous legal saga, occurred in 1951. The Court heard the appeals of Shepherd and Irvin, who had been convicted of rape and sentenced to death. In the case, Shepherd v. Florida, the Court unanimously reversed their criminal convictions.

The U.S. Supreme Court issued no opinion explaining this decision. The Court simply announced, per curiam, that the Florida Supreme Court’s judgment affirming Shepherd’s and Irvin’s convictions and sentences was reversed. As authority, the U.S. Supreme Court cited its decision a year earlier in Cassell v. Texas. In that case, the Court had reversed a black man’s murder conviction because he had been indicted by a grand jury from which black people had been excluded, in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. The same had been true, the Court was signaling, of the Florida grand jury that had indicted Shepherd and Irvin.

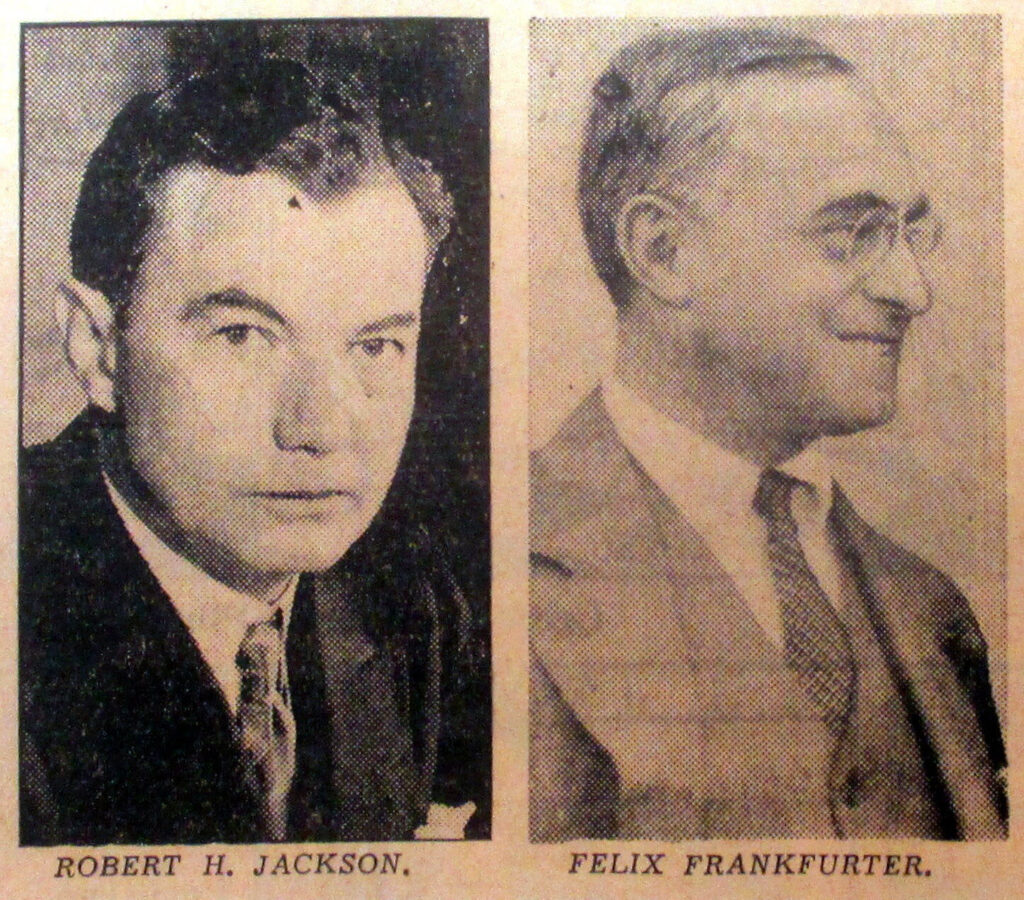

One Supreme Court justice, Robert H. Jackson, did write in the Shepherd case. He filed an opinion concurring in the result reached by the Court. In Jackson’s view, however, to reverse these convictions for discrimination in jury selection was “to stress the trivial and ignore the important.”

Justice Jackson believed that the serious constitutional issue in the case was prejudicial pretrial publicity. There had been pretrial press reports, for example, that the defendants had confessed, but this was never substantiated by evidence at trial. Jackson concluded that these press reports, which he called “one of the worst menaces to American justice,” had so permeated the atmosphere surrounding the trial that it denied due process to Shepherd and Irvin.

Justice Jackson disputed the Court’s apparent idea that a black juror in the Groveland case could have made a difference:

“I do not see, as a practical matter, how any Negro on the jury would have dared to cause a disagreement or acquittal. The only chance these Negroes had of acquittal would have been in the courage and decency of some sturdy and forthright white person of sufficient standing to face and live down the odium among his white neighbors that such a vote, if required, would have brought.”

Justice Felix Frankfurter joined Justice Jackson in his Shepherd opinion. In private, Frankfurter joined with special emphasis. When Jackson circulated to his colleagues his proposed concurring opinion, only Frankfurter responded. He penned a note asking Jackson to “[p]lease honor me by letting me join this.”

when they were being mentioned a possible Supreme Court appointees.

In Justice Jackson’s Shepherd opinion, his reference to a “sturdy and forthright white person of sufficient standing to face and live down … odium among his white neighbors” was about a hypothetical white juror voting to acquit the Groveland defendants.

The language also seems self-referential. Jackson was describing, to a degree, what he, joined by Frankfurter, was doing by judging and writing in the case.

Washington National Cathedral funeral of Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson (Life magazine photograph).

To read Jackson’s Shepherd v. Florida opinion in full, click here.