Robert H. Jackson’s ancestors included Englishmen, but it seems that they were not loyal to the crown.

His great-great-grandfather Uri Jackson, who lived from around 1750 until at least 1781, was a farmer in colonial Connecticut. He also served as a corporal in the Connecticut militia during the Revolutionary War.

One of Robert’s great-grandfathers on his father’s side, George Ferros Eldred, was born in London, in the Middle Temple, in 1787. His father William, a barrister, was under treasurer of the Middle Temple, one of the Inns of Court that were homes of English lawyers. But George was William Eldred’s younger son. As Robert Jackson commented in the early 1950s, “younger sons, of course, did not succeed their fathers under the British scheme of things. He came to America.”

Gravestone of George Eldred (died 1878) & Laura Cady Eldred (died 1891), Spring Creek Cemetery, Spring Creek, PennsylvaniaRobert Jackson had various encounters with the top of “the British scheme of things.” The first occurred in summer 1924. Robert Jackson, then a successful New York State lawyer living and working in Jamestown, attended, with his wife Irene—a Kingston [ba-dum-bump], New York, native—an American Bar Association week-long meeting in London with the English Inns of Court, the Law Society, and the Canadian Bar Association. On July 24, 1924, the Jacksons were among many guests who attended a garden party that King George V and Queen Mary hosted at Buckingham Palace.

The Jacksons’ next brush with British royalty occurred in Washington in 1938. King George VI and Queen Elizabeth were visiting the U.S. Robert Jackson was Solicitor General of the U.S. On June 8, he and Irene attended a White House performance for the King and Queen of American music. And the next afternoon, the Jacksons attended a party that British Ambassador Ronald Lindsay and his wife Lady Elizabeth Lindsay (an American) gave for the King and Queen in the garden of the British Embassy.

Seven years later, in spring 1945, as Robert H. Jackson was completing his fourth year of service as an associate justice on the U.S. Supreme Court, President Truman appointed him to serve as U.S. chief of counsel for the prosecution of Axis war criminals in the European Theater. This became Jackson’s fall 1945—summer 1946 job as chief prosecutor at Nuremberg of Nazi war criminals. Before Jackson got to Nuremberg, however, he lived and worked during summer 1945 in London, negotiating with allied government counterparts to create the Nuremberg international court and define its charter.

On August 15, 1945, Justice Jackson took an opportunity to see King George in action at a formal occasion, the opening of Parliament. Jackson obtained a ticket to stand in the Royal Gallery to hear the King’s address. He saw robed and bewigged Lord Chancellor Jowitt, with whom Jackson had worked in the war crimes court negotiations, escort the King (“entirely impassive,” Jackson said later) and the Queen (“bowing to the occupants of each box”). They walked behind his carried crown, “through a line of Beefeaters in scarlet uniforms.” Alas, Jackson in the gallery was unable to hear the King’s address.

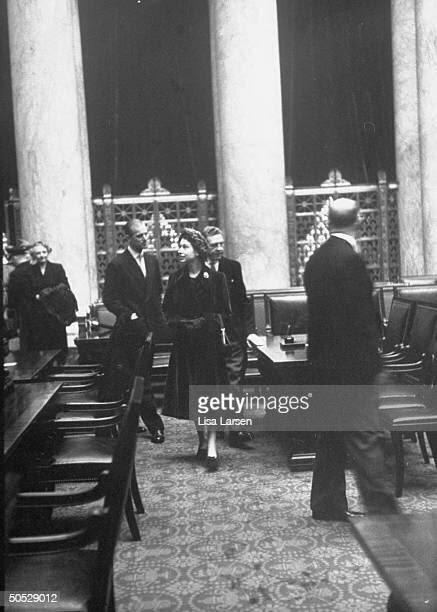

Justice Jackson definitely met British royalty at the Supreme Court in 1951. On November 2, 1951, Chief Justice Vinson hosted Princess Elizabeth—soon to become Queen Elizabeth II—and her husband Duke Philip at the Court. The Princess and Duke entered by the Court’s front entrance. They were escorted to the Chief Justice’s chambers. Each of the associate justices, including Jackson, was assembled there and met them. The royals’ tour also included the courtroom. I am sure that it was pleasant and awkwardly official. To my knowledge, Justice Jackson wrote nothing about it.

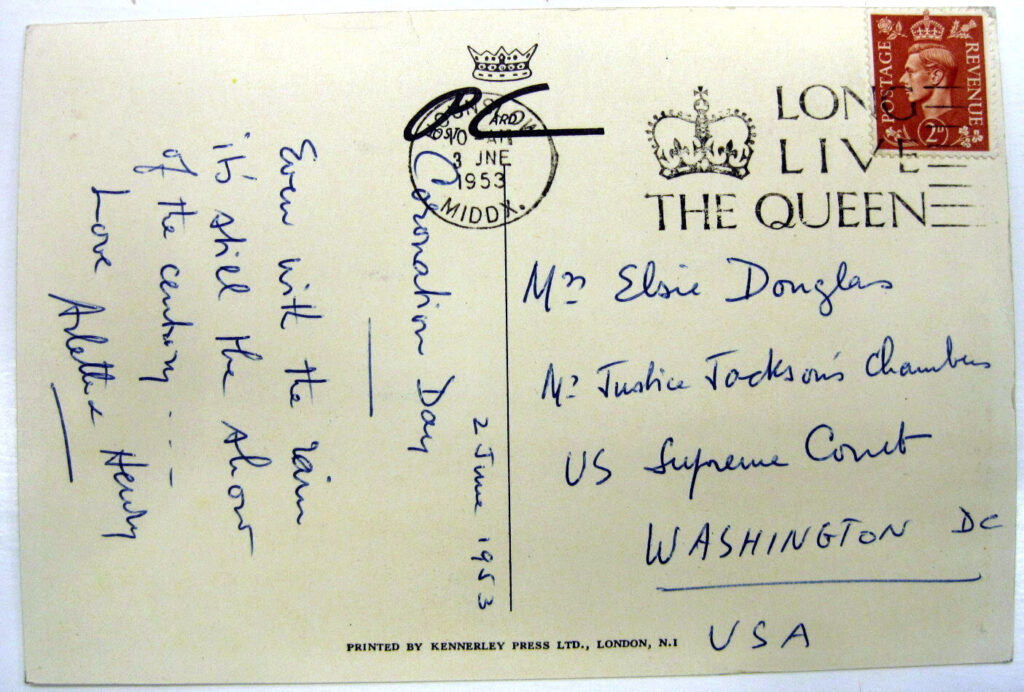

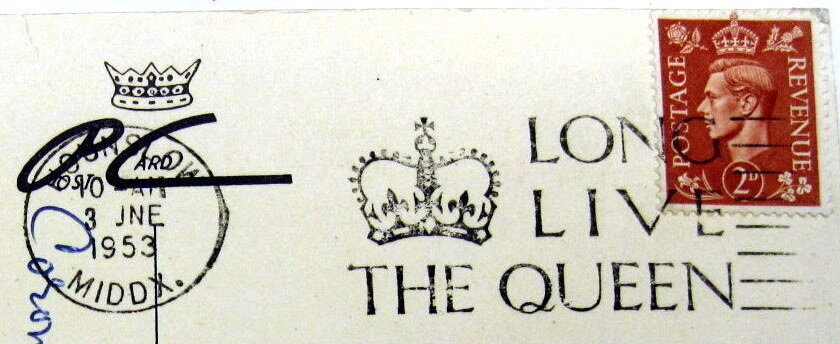

A final Jackson, or at least a Jackson files, tidbit regarding the British royal family dates to Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation. It occurred in London on June 2, 1953. A French couple, Henry and Arlette Leger, who had worked on Jackson’s Nuremberg staff, were in London on that day. They wrote a postcard noting the occasion to Elsie Douglas, Jackson’s secretary at the Court who had been with him in London and Nuremberg during 1945 and 1946 and became a friend of the Legers. They mailed it with a King George postage stamp.

The postmark, applied the next day, is striking. Cancelling the King George stamp, it announces an official wish that in fact transpired: “Long Live the Queen.”