Following yesterday morning’s state funeral service at Westminster Abbey in London for Queen Elizabeth II, members of her family, some officials from Commonwealth nations, and some members of royal families from around the world traveled to St. George’s Chapel in Windsor Castle. The Queen’s remains were interred there.

Many heads of state, senior foreign government ministers, and international diplomats who had attended the funeral did not travel from London to Windsor. Instead, United Kingdom Foreign Minister James Cleverly hosted them at a reception at Church House. It is a stately red-brick building in an enclosed yard on the Westminster Abbey grounds.

Church House is, as its name communicates, the headquarters office of the Church of England. In June 1940, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth, parents of then-Princess Elizabeth (the future Queen Elizabeth II), opened this Church House building. In 1945, the United Nations Preparatory Commission met there, as did, in 1946, the U.N. Security Council. In 1988, Queen Elizabeth II unveiled a tablet at Church House commemorating the centenary of the Church corporation.

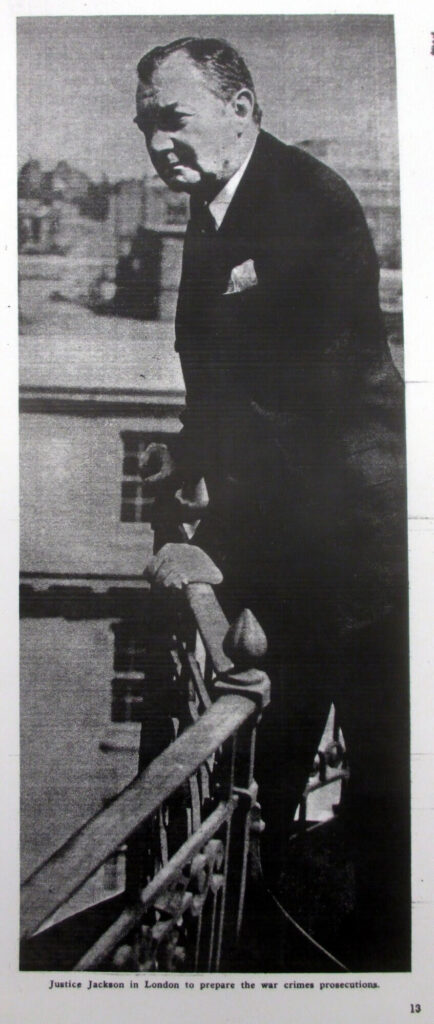

Church House is notable for all of these things, but it is perhaps most notable for being in summer 1945 the site of the London Conference of representatives of the United States, the U.K., the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, and the Republic of France. The U.S. representative—President Truman’s appointee “to act as the Representative of the United States and as its Chief of Counsel in preparing and prosecuting charges of atrocities and war crimes against such of the leaders of the European Axis powers and their principal agents and accessories as the United States may agree with any of the United Nations to bring to trial before an international military tribunal”—was U.S. Supreme Court Justice Robert H. Jackson.

Over two-plus months that summer, the London Conference representatives met in official sessions at Church House. They fulfilled and advanced the declarations that their government leaders had made during World War II: that the major German Nazi leaders were international law violators; that they were arch-criminals whose offenses transcended particular locations and affected more than particular victims; and that they should be punished by an international process.

The U.S. representatives on the right side of the table are, from top,

Major General William J. Donovan, Chief of Counsel Robert H. Jackson,

Colonel Murray C. Bernays (GSC), Ensign William E. Jackson (USNR), and Mrs. Elsie L. Douglas.

On August 8, 1945, the London Conference concluded with the signing, in Church House, of the London Agreement. It was and is a historic event in international diplomacy and peacemaking and a cardinal development in international law.

In the London Agreement, the Allies announced their decision to take a path of law and public accountability rather than to act summarily, with their unlimited military power and their high desire for vengeance, against their Nazi prisoners. The Allies chose, despite the absence of a peace treaty or any other legal or political constraint, to address the possible legal culpability of former Nazi leaders through a public, juridical process. To do so, the Allies created, in the London Agreement, an international criminal court, the International Military Tribunal. In a Charter annexed to the Agreement, they prescribed the IMT’s constitution, jurisdiction, and functions.

Justice Robert H. Jackson, and Judge Robert Falco of France sign the London Agreement.

(U.S.S.R. signatories General Iona T. Nikitchenko and Professor Aron N. Trainin are not pictured.)

I hope that some of the officials who gathered, mourned, and socialized yesterday at Church House knew and recalled that they were at the 1945 London Conference and London Agreement site—the site of the legal birth of the international Nuremberg trial.