Robert and Irene Jackson purchased Hickory Hill, a six-acre property in rural McLean, Virginia, in Summer 1941. At that time, Jackson was United States Attorney General and a nominee to serve as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court. He soon was confirmed and commissioned as a justice. The Jacksons closed on their purchase of Hickory Hill and lived there for the rest of his life.

Robert was born on a Pennsylvania farm and then grew up in the rural areas of western New York State. Irene came from a city, Kingston, New York, but she also enjoyed the outdoors. In particular, they both were horse people, so it was a joy for them to live at Hickory Hill, to have horses in their own barn at their home, to sometimes raise pigs and other animals too, to grow lots of vegetables, and to have open space, all not too far from Robert’s Supreme Court workplace and their deep ties in Washington, D.C.

The Hickory Hill property—an antebellum house, expansive lawn, trees, stable, horses, other animals, gardens, cars, and other machinery—was a lot to manage, and of course Justice Jackson had a demanding day job. So he and Irene employed a handyman/caretaker, Stuart Loy, who really ran and maintained the place. Loy, a native Virginian, was highly skilled and a very hard worker. He became the Jacksons’ friend, joining them and other family members and friends on horse rides, hikes, and fishing trips.

Although Stuart Loy had the big job of maintaining Hickory Hill, he also did at least some moonlighting. Maybe it was paid, but my guess is that he just volunteered sometimes to assist others in the area.

One instance of this occurred on Friday evening, May 2, 1952. Loy used an old rotary mower to cut the lawn of the Jacksons’ friends Sam and Mary Neel, who lived with their young family in the house next door. As Loy was mowing, a blade flew off, severing his Achilles tendon. Mary Neel bandaged him up and took him to a hospital.

The Jacksons were not home, it seems, when Loy was injured. Perhaps Justice Jackson was working late at the Supreme Court, preparing for the justices’ conference the next morning. (In early May 1952, the justices were busy drafting opinions in cases that had been argued that term. They also were considering appeals and petitions for review, including some that were momentous. In the next days, they would agree to hear on an emergency basis Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Sawyer, a case that produced one of the leading decisions in Court history. The case concerned the constitutionality of President Truman’s seizure of the nation’s steel mills to prevent them from being shut down by a steelworkers’ strike during that Korean War period. (A few weeks later, the Court decided that the president had acted unconstitutionally.)

A doctor treated Stuart Loy’s injury. Soon all was well—Loy, after being laid up for a time, recovered and resumed working.

Because Loy was injured while working, the doctor reported the incident to Virginia’s Industrial Commission. He also reported that Justice Jackson was Loy’s employer.

The Commonwealth of Virginia checked its records and found no indication that employer Jackson had workmen’s compensation insurance. State law required employers of seven or more people to purchase and maintain such insurance.

On July 24, Virginia wrote to Justice Jackson. It notified him of the situation, asked how many employees he had, directed him to show that if he had seven or more employees he had insurance, and added that he faced the possibility of a fine “for failure to report promptly and properly accidents.”

Justice Jackson did not receive this letter. He was on vacation at the Bohemian Grove in California. He thus did not reply.

The Commonwealth of Virginia, apparently feeling that Jackson was ignoring its letter, sent him a second letter on August 7. It repeated that Jackson had a duty to report to the Commonwealth on his number of employees and his workmen’s compensation insurance coverage. Virginia also stated, perhaps showing some deference to Jackson’s position as a Supreme Court justice, that it was giving him ten extra days to respond.

By Saturday, August 9, Justice Jackson was back in Washington. He soon found the Commonwealth of Virginia’s two letters to him.

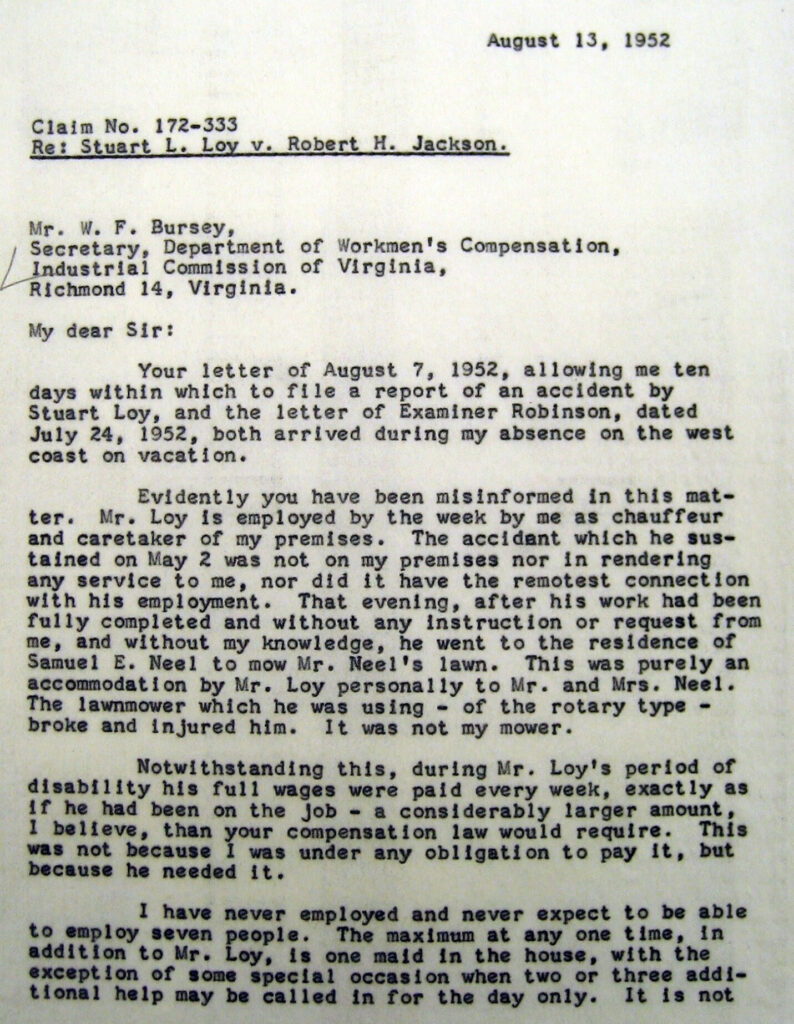

On August 13, Jackson wrote back to Virginia. He reported that:

- Stuart Loy was injured at the Neels’ home, not at the Jacksons’;

- Loy was injured by a mower that was not Jackson’s;

- he employs Loy “by the week … as chauffeur and caretaker of my premises”;

- he paid Loy’s full wages every week when he was recovering from the injury “because he needed it”;

- he (Jackson) did not employ seven people—at most he employed Loy plus one maid in the house, and sometimes 2-3 more day helpers on special occasions.

And that was, it seems, the end of it. At least that is the end of the correspondence in the papers that Justice Jackson preserved as a set.

It seems that Jackson’s conduct, once he got around to explaining it, was fully satisfactory.

Stuart Loy continued to work happily for the Jacksons and to be friendly with the Neels.