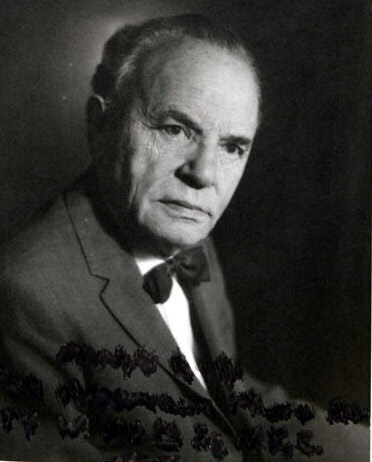

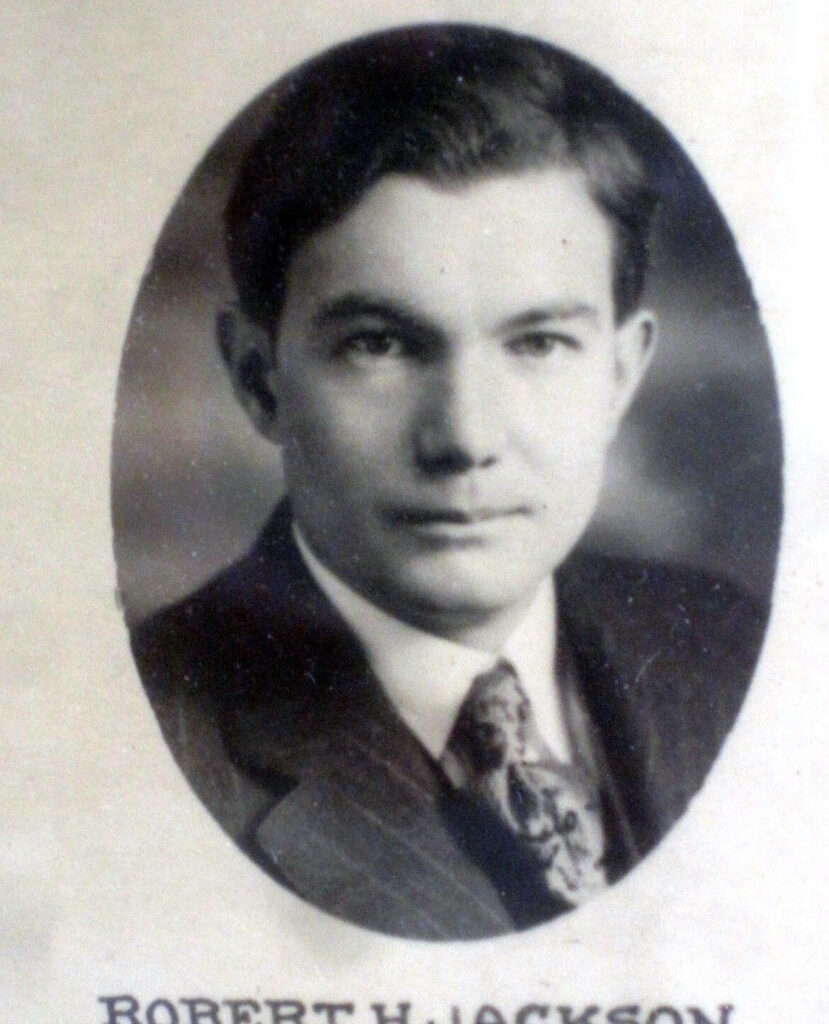

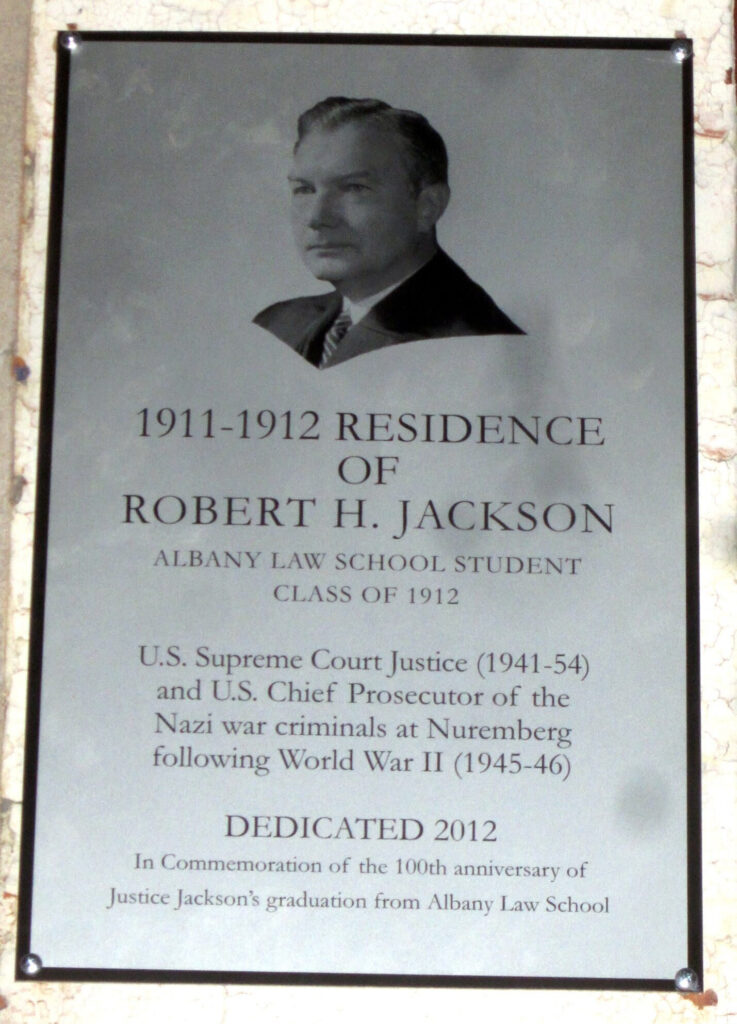

On Monday, April 1, 1940, Robert H. Jackson—age forty-eight, three months into his service as Attorney General of the United States—gave one of his most important, famous, enduring speeches: The Federal Prosecutor. He spoke on that day to the country’s chief federal prosecutors, the U.S. Attorneys who then were serving in each Federal Judicial District across the country. They were assembled in the Great Hall at the U.S. Department of Justice in Washington, D.C., for the Second Annual Conference of U.S. Attorneys.

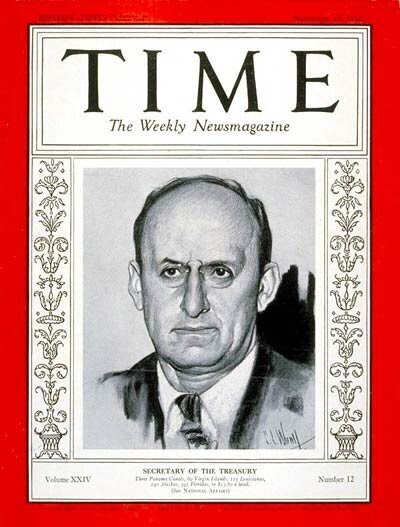

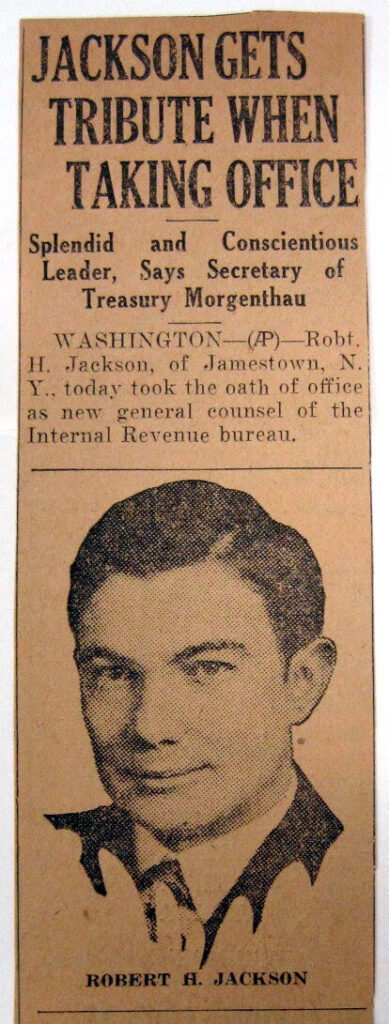

Robert Jackson had moved up to the position of U.S. Attorney General from having been the Solicitor General of the U.S., which then was DOJ’s number two position.

As the new Attorney General, Jackson was leading a Department of Justice that his predecessor for one year, Attorney General Frank Murphy, had run politically and in a self-aggrandizing fashion. DOJ personnel were, after a year of that, demoralized. This Jackson speech was clean up work. He urged the renewal of DOJ through an elevated, ethical, depoliticized vision of proper conduct by federal prosecutors. Jackson’s speech was, you will note, the antithesis of an April Fool’s Day joke.

Attorney General Jackson’s speech is quoted often. I recall first reading some of it in Justice Scalia’s dissenting opinion in Morrison v. Olson (1988), which quotes from it liberally. I then got the Jackson speech and read all of it (which does not take long), to get a fuller understanding of his words and philosophy. I have read Jackson’s speech many times since then. A senior DOJ official, for example, handed it out as assigned reading to many attorneys when I worked in DOJ in the 1990s, and I completed the assignment. I have heard or read most Attorneys General, Deputy Attorneys General, and other senior DOJ officials, including recently, quote from Jackson’s speech in their own speeches, other public remarks, and written work.

Attorney General Jackson’s speech, which follows, bears reading in full, and regularly.

Jackson’s speech also bears absorption and implementation today by every gentleperson who wields prosecutorial power.

* * *

The Federal Prosecutor

By Robert H. Jackson

Attorney General of the United States

April 1, 1940

It would probably be within the range of that exaggeration permitted in Washington to say that assembled in this room is one of the most powerful peace-time forces known to our country. The prosecutor has more control over life, liberty, and reputation than any other person in America. His discretion is tremendous. He can have citizens investigated and, if he is that kind of person, he can have this done to the tune of public statements and veiled or unveiled intimations. Or the prosecutor may choose a more subtle course and simply have a citizen’s friends interviewed. The prosecutor can order arrests, present cases to the grand jury in secret session, and on the basis of his one-sided presentation of the facts, can cause the citizen to be indicted and held for trial. He may dismiss the case before trial, in which case the defense never has a chance to be heard. Or he may go on with a public trial. If he obtains a conviction, the prosecutor can still make recommendations as to sentence, as to whether the prisoner should get probation or a suspended sentence, and after he is put away, as to whether he is a fit subject for parole. While the prosecutor at his best is one of the most beneficent forces in our society, when he acts from malice or other base motives, he is one of the worst.

These powers have been granted to our law-enforcement agencies because it seems necessary that such a power to prosecute be lodged somewhere. This authority has been granted by people who really wanted the right thing done—wanted crime eliminated—but also wanted the best in our American traditions preserved.

Because of this immense power to strike at citizens, not with mere individual strength, but with all the force of government itself, the post of Federal District Attorney from the very beginning has been safeguard by presidential appointment, requiring confirmation of the Senate of the United States. You are thus required to win an expression of confidence in your character by both the legislative and the executive branches of the government before assuming the responsibilities of a federal prosecutor.

Your responsibility in your several districts for law enforcement and for its methods cannot be wholly surrendered to Washington, and ought not to be assumed by a centralized Department of Justice. It is an unusual and rare instance in which the local District Attorney should be superseded in the handling of litigation, except where he requests help of Washington. It is also clear that with his knowledge of local sentiment and opinion, his contact with and intimate knowledge of the views of the court, and his acquaintance with the feelings of the group from which jurors are drawn, it is an unusual case in which his judgment should be overruled.

Experience, however, has demonstrated that some measure of centralized control is necessary. In the absence of it different district attorneys were striving for different interpretations or applications of an Act, or were pursuing different conceptions of policy. Also, to put it mildly, there were differences in the degree of diligence and zeal in different districts. To promote uniformity of policy and action, to establish some standards of performance, and to make available specialized help, some degree of centralized administration was found necessary.

Our problem, of course, is to balance these opposing considerations. I desire to avoid any lessening of the prestige and influence of the district attorneys in their districts. At the same time we must proceed in all districts with that uniformity of policy which is necessary to the prestige of federal law.

Nothing better can come out of this meeting of law enforcement officers than a rededication to the spirit of fair play and decency that should animate the federal prosecutor. Your positions are of such independence and importance that while you are being diligent, strict, and vigorous in law enforcement you can also afford to be just. Although the government technically loses its case, it has really won if justice has been done. The lawyer in public office is justified in seeking to leave behind him a good record. But he must remember that his most alert and severe, but just, judges will be the members of his own profession, and that lawyers rest their good opinion of each other not merely on results accomplished but on the quality of the performance. Reputation has been called “the shadow cast by one’s daily life.” Any prosecutor who risks his day-to-day professional name for fair dealing to build up statistics of success has a perverted sense of practical values, as well as defects of character. Whether one seeks promotion to a judgeship, as many prosecutors rightly do, or whether he returns to private practice, he can have no better asset than to have his profession recognize that his attitude toward those who feel his power has been dispassionate, reasonable and just.

The federal prosecutor has now been prohibited from engaging in political activities. I am convinced that a good-faith acceptance of the spirit and letter of that doctrine will relieve many district attorneys from the embarrassment of what have heretofore been regarded as legitimate expectations of political service. There can also be no doubt that to be closely identified with the intrigue, the money raising, and the machinery of a particular party or faction may present a prosecuting officer with embarrassing alignments and associations. I think the Hatch Act should be utilized by federal prosecutors as a protection against demands on their time and their prestige to participate in the operation of the machinery of practical politics.

There is a most important reason why the prosecutor should have, as nearly as possible, a detached and impartial view of all groups in his community. Law enforcement is not automatic. It isn’t blind. One of the greatest difficulties of the position of prosecutor is that he must pick his cases, because no prosecutor can even investigate all of the cases in which he receives complaints. If the Department of Justice were to make even a pretense of reaching every probable violation of federal law, ten times its present staff would be inadequate. We know that no local police force can strictly enforce the traffic laws, or it would arrest half the driving population on any given morning. What every prosecutor is practically required to do it to select the cases for prosecution and to select those in which the offense is the most flagrant, the public harm the greatest, and the proof the most certain.

If the prosecutor is obliged to choose his cases, it follows that he can choose his defendants. Therein is the most dangerous power of the prosecutor: that he will pick people that he thinks he should get, rather than pick cases that need to be prosecuted. With the law books filled with a great assortment of crimes, a prosecutor stands a fair chance of finding at least a technical violation of some act on the part of almost anyone. In such a case, it is not a question of discovering the commission of a crime and then looking for the man who has committed it, it is a question of picking the man and then searching the law books, or putting investigators to work, to pin some offense on him. It is in this realm—in which the prosecutor picks some person whom he dislikes or desires to embarrass, or selects some group of unpopular persons and then looks for an offense, that the greatest danger of abuse of prosecuting power lies. It is here that law enforcement becomes personal, and the real crime becomes that of being unpopular with the predominant or governing group, being attached to the wrong political views, or being personally obnoxious to or in the way of the prosecutor himself.

In times of fear or hysteria political, racial, religious, social, and economic groups, often from the best of motives, cry for the scalps of individuals or groups because they do not like their views. Particularly do we need to be dispassionate and courageous in those cases which deal with so-called “subversive activities.” They are dangerous to civil liberty because the prosecutor has no definite standards to determine what constitutes a “subversive activity,” such as we have for murder or larceny. Activities which seem benevolent and helpful to wage earners, persons on relief, or those who are disadvantaged in the struggle for existence may be regarded as “subversive” by those whose property interests might be burdened or affected thereby. Those who are in office are apt to regard as “subversive” the activities of any of those who would bring about a change of administration. Some of our soundest constitutional doctrines were once punished as subversive. We must not forget that it was not so long ago that both the term “Republican” and the term “Democrat” were epithets with sinister meaning to denote persons of radical tendencies that were “subversive” of the order of things then dominant.

In the enforcement of laws which protect our national integrity and existence, we should prosecute any and every act of violation, but only overt acts, not the expression of opinion, or activities such as the holding of meetings, petitioning of Congress, or dissemination of news or opinions. Only by extreme care can we protect the spirit as well as the letter of our civil liberties, and to do so is a responsibility of the federal prosecutor.

Another delicate task is to distinguish between the federal and the local in law-enforcement activities. We must bear in mind that we are concerned only with the prosecution of acts which the Congress has made federal offenses. Those acts we should prosecute regardless of local sentiment, regardless of whether it exposes lax local enforcement, regardless of whether it makes or breaks local politicians.

But outside of federal law each locality has the right under our system of government to fix its own standards of law enforcement and of morals. And the moral climate of the United States is as varied as its physical climate. For example, some states legalize and permit gambling, some states prohibit it legislatively and protect it administratively, and some try to prohibit it entirely. The same variation of attitudes towards other law-enforcement problems exists. The federal government could not enforce one kind of law in one place and another kind elsewhere. It could hardly adopt strict standards for loose states or loose standards for strict states without doing violence to local sentiment. In spite of the temptation to divert our power to local conditions where they have become offensive to our sense of decency, the only long-term policy that will save federal justice from being discredited by entanglements with local politics is that it confine itself to strict and impartial enforcement of federal law, letting the chips fall in the community where they may. Just as there should be no permitting of local considerations to stop federal enforcement, so there should be no striving to enlarge our power over local affairs and no use of federal prosecutions to exert an indirect influence that would be unlawful if exerted directly.

The qualities of a good prosecutor are as elusive and as impossible to define as those which mark a gentleman. And those who need to be told would not understand it anyway. A sensitiveness to fair play and sportsmanship is perhaps the best protection against the abuse of power, and the citizen’s safety lies in the prosecutor who tempers zeal with human kindness, who seeks truth and not victims, who serves the law and not factional purposes, and who approaches his task with humility.