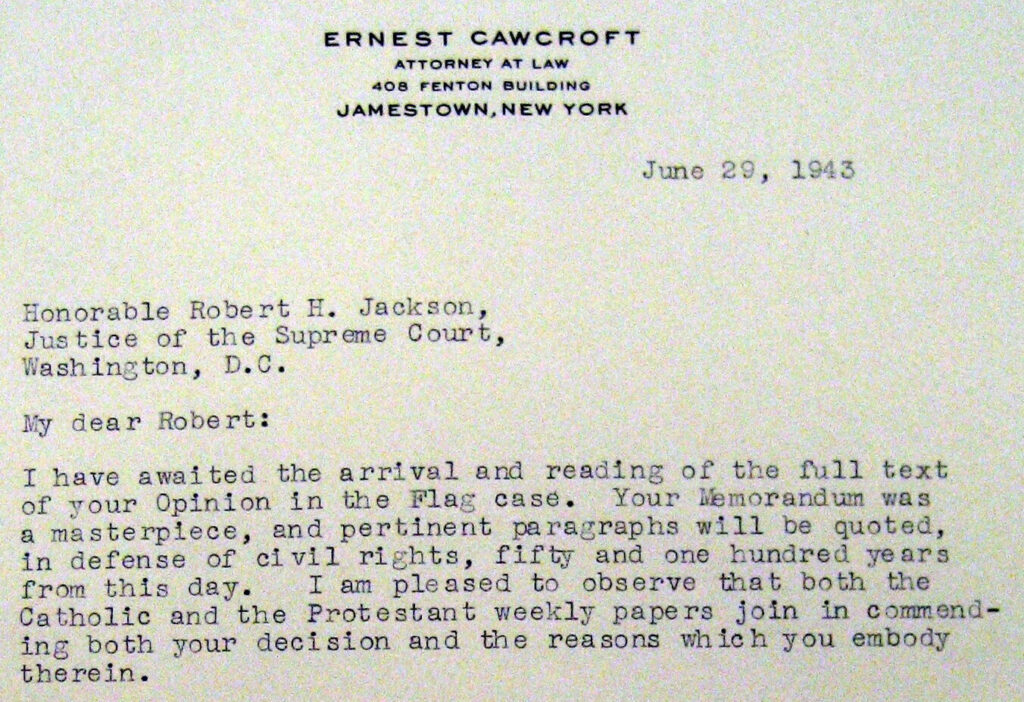

During the U.S. Supreme Court’s 1952-1953 term, young lawyer Donald Cronson, a graduate of the University of Chicago Law School, was one of Justice Robert H. Jackson’s two law clerks. (Jackson’s other clerk was another young lawyer, William Rehnquist of Milwaukee, a graduate of Stanford Law School.)

The first months of that Court term were busy and eventful, for all of the justices and for Justice Jackson in particular. In October 1952, for example, the justices decided not to review the federal atom bomb espionage convictions and death sentences imposed on Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. (The Rosenbergs then petitioned for rehearings, which the justices denied in November.) The Court heard oral arguments that Fall in dozens of cases; one of lasting note was United States v. Reynolds, a national security case involving the so-called state secrets privilege. The Court decided numerous cases that Fall, including nine in which Jackson wrote opinions, a few for the Court majority and others for himself. The latter included his dissenting opinion in Arrowsmith v. Commissioner of Internal Revenue, about deference owed to the U.S. Tax Court, and his dissenting opinion in Kedroff v. St. Nicholas Cathedral of the Russian Orthodox Church in North America, about a church property dispute. In October, Jackson finished writing and submitted for publication, unsolicited, his fascinating essay, “Falstaff’s Descendants in Pennsylvania Courts,” that the University of Pennsylvania Law Review published two months later. In November he testified before a U.S. House of Representatives committee (the Select Committee on the Katyn Forest massacre), which was investigating alleged misconduct by Jackson when he was U.S. chief prosecutor at Nuremberg of Nazi war criminals in 1945-1946. And in December 1952, the Supreme Court heard, over three days, the first round of oral arguments in the five cases—Brown v. Board of Education and its companion cases—that challenged the constitutionality of States and the District of Columbia racially segregating public school children.

During those months, Justice Jackson kept his law clerks Cronson and Rehnquist busy. They wrote memoranda on petitions seeking Court review, performed research, and read and commented on Jackson draft opinions. (They did not draft these opinions for Jackson; he did almost all of his own opinion-writing.)

In December 1952, the Court sat in public session for two weeks, from Monday, December 8, through Friday, December 19. On Saturday, December 20, the nine justices met in their customary Saturday private conference, to discuss petitions and argued cases. Jackson and his law clerks generally worked six-day weeks at the Court. I believe that both Jackson clerks were present at the Court on Saturday, December 20.

Then Don Cronson traveled to New York City for a two-day, pre-Christmas belated “weekend”—Sunday, December 21, and Monday, December 22. Cronson surely got Jackson’s permission to be away from the Court on that workday Monday. Cronson evidently told Jackson—and this might have been the condition that got Jackson to approve Cronson’s Monday absence—that he (Cronson) would be back at work on Tuesday, December 23.

Then something caused Justice Jackson to have further thoughts.

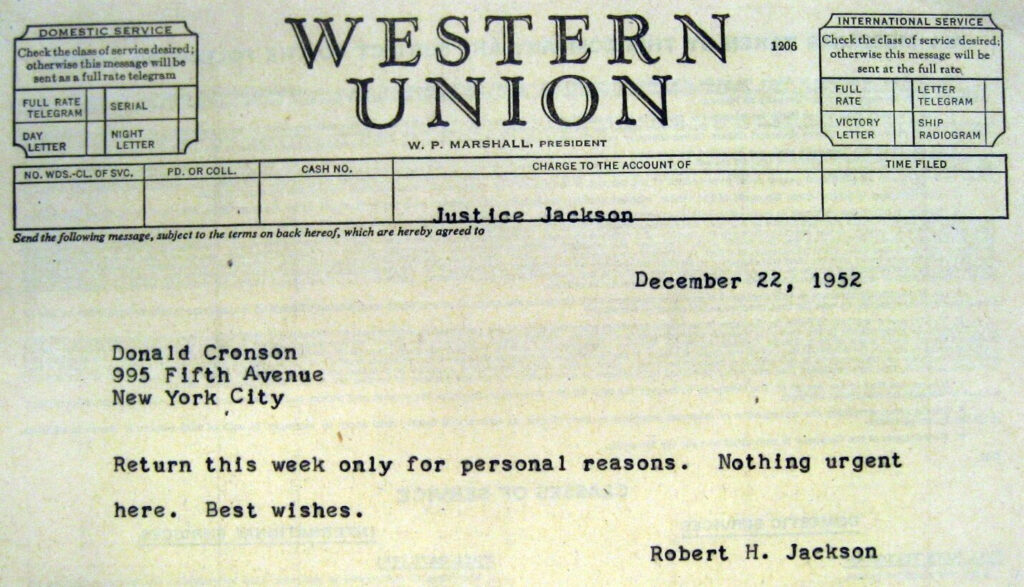

On Monday, December 22, Jackson sent a telegram to Don Cronson in New York City. He was staying at an apartment on Manhattan’s Upper East Side.

Jackson told Cronson, in effect, to take the rest of the week off, because there was “nothing urgent” at the Supreme Court:

* * *

I hope that you will, this week, experience days off, a wonderful holiday season, and as little urgency as U.S. Supreme Court justices feel…. or at least as little urgency as Justice Jackson felt at Christmastime in 1952.

Thank you very much for your continuing interest in and promotion of the Jackson List.

“See” you in 2024.