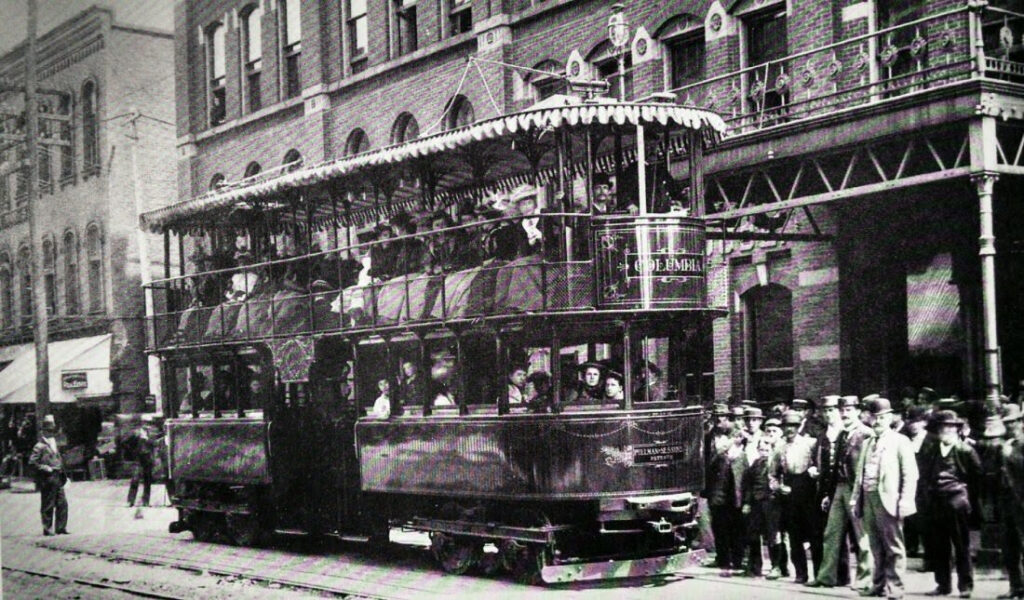

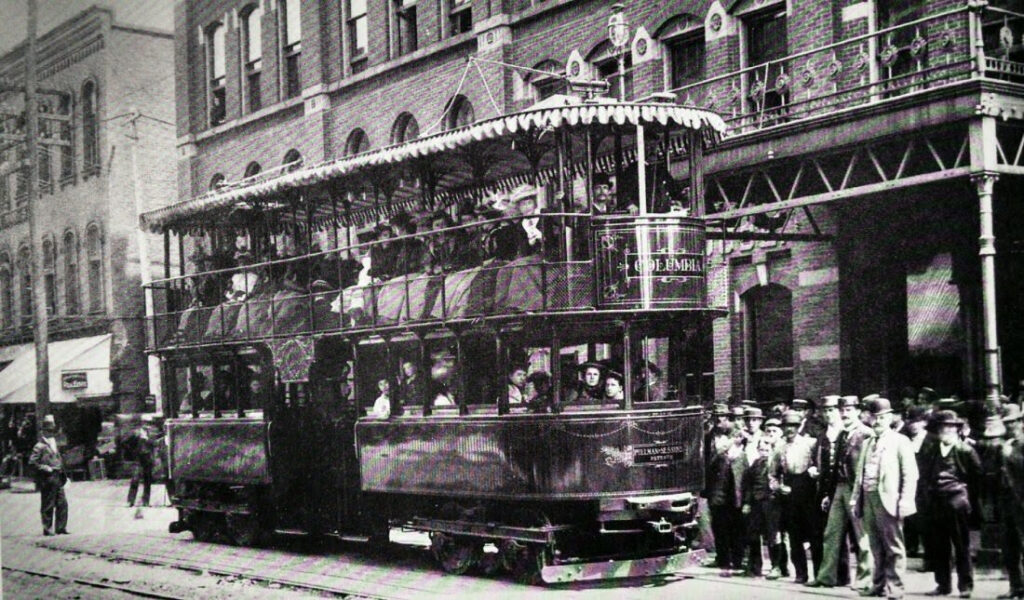

In 1884, the Jamestown Street Railway company began to provide horse-drawn street car service to the public in Jamestown, Chautauqua County, New York.

Seven years later, the company began to run electric trolley cars. Overhead tension wires, supported by poles and arms, connected to poles and wires atop the trolleys and powered their traction motors.

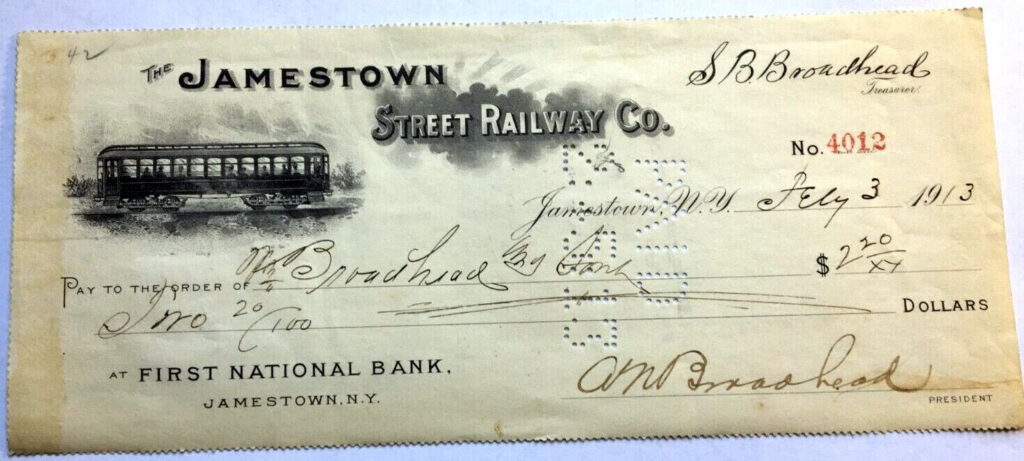

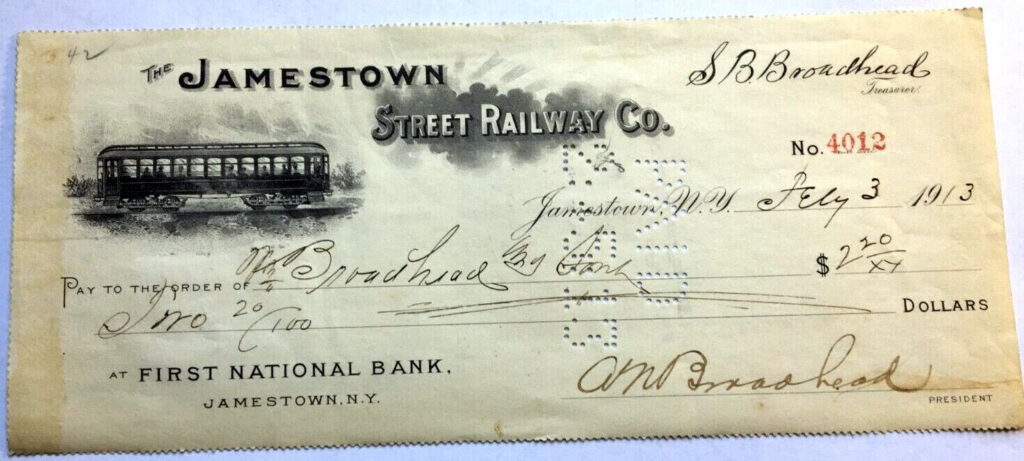

The Jamestown Street Railway, owned by the Broadhead family, employed many workers. The business was successful. And the Broadheads were wealthy, including from their principal business, Broadhead Worsted Mills. They also owned the Broadhead Power House, which supplied electricity to the trolley lines.

On May 1, 1913, Jamestown Street Railway’s workers, seeking higher pay and union recognition, went on strike. Nearly 300 men walked off the job. Street Railway service was reduced, including to no trolleys running after dark.

A.N. (Almet Norval) Broadhead, president of Street Railway, believed in a low-wage economy. So he fought the strike as a business matter. He also fought it personally. For example, he at least once took the controller handle of a street car and ran it through streets where strikers and their supporters were gathered.

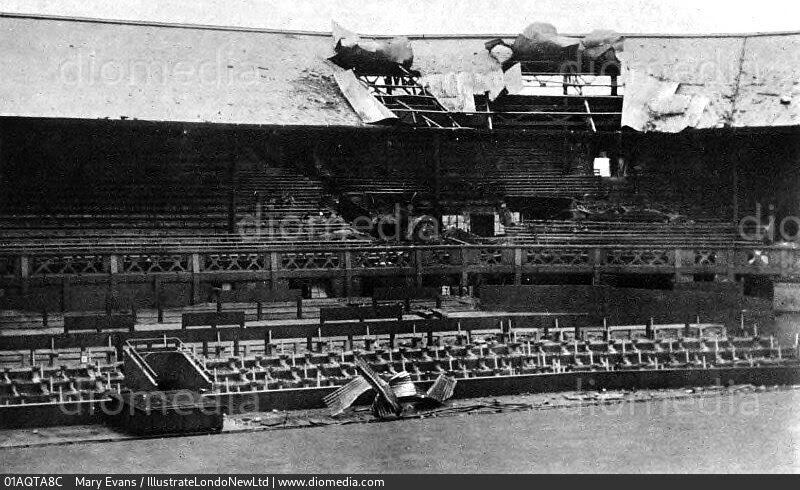

In efforts, probably not carefully considered, to help their cause, some strikers began to damage Street Railway and other Broadhead properties. They cut down poles supporting wires that powered the trolleys from Jamestown to suburban Lakewood. They sabotaged track switches and signals. Later in May, they became more violent, damaging the street car barn, rioting and throwing rocks through windows at Broadhead Worsted Mills, and then marching as a mob on Broadhead’s mansion, located on Jamestown’s South Main Street.

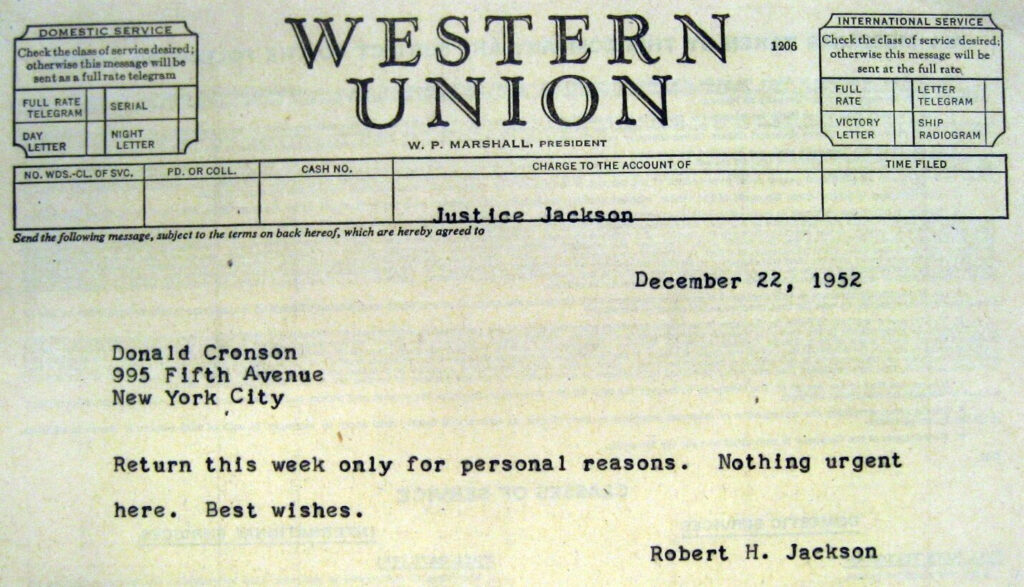

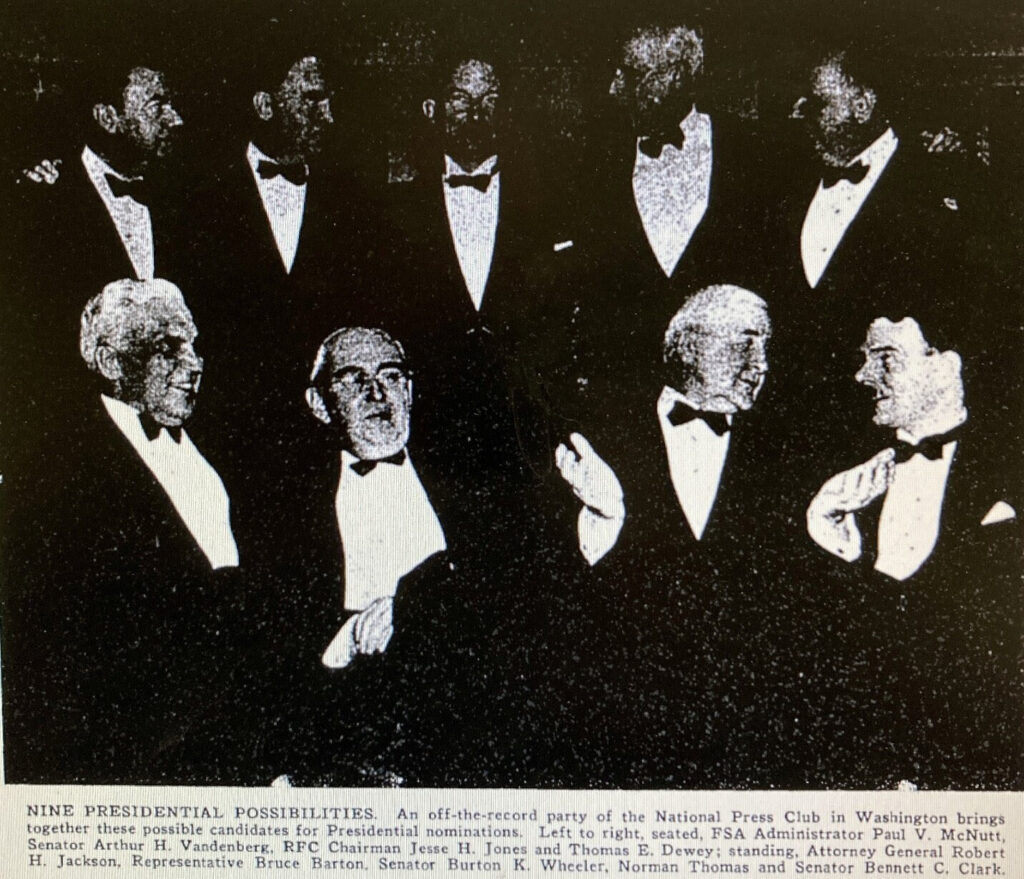

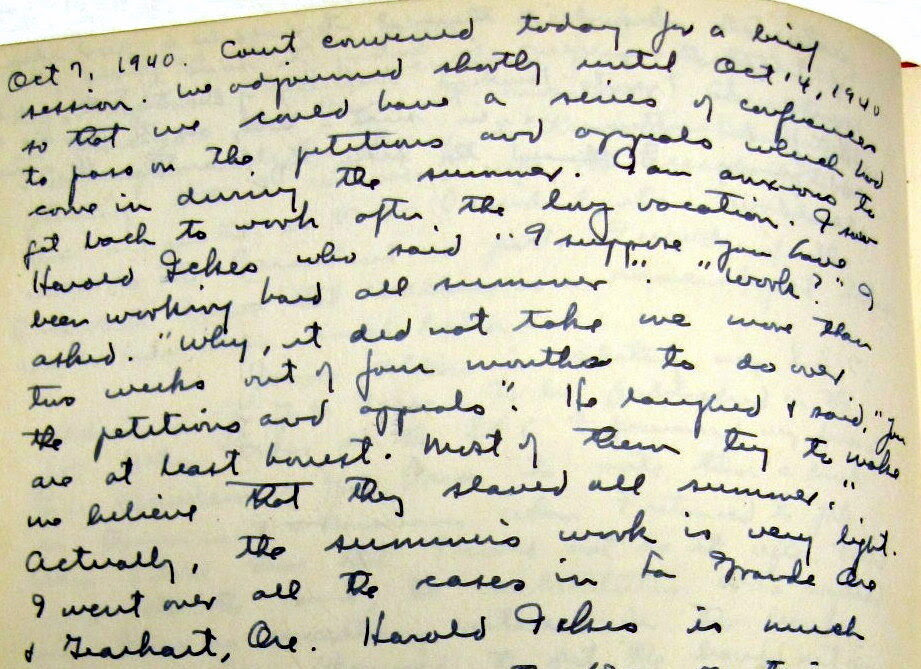

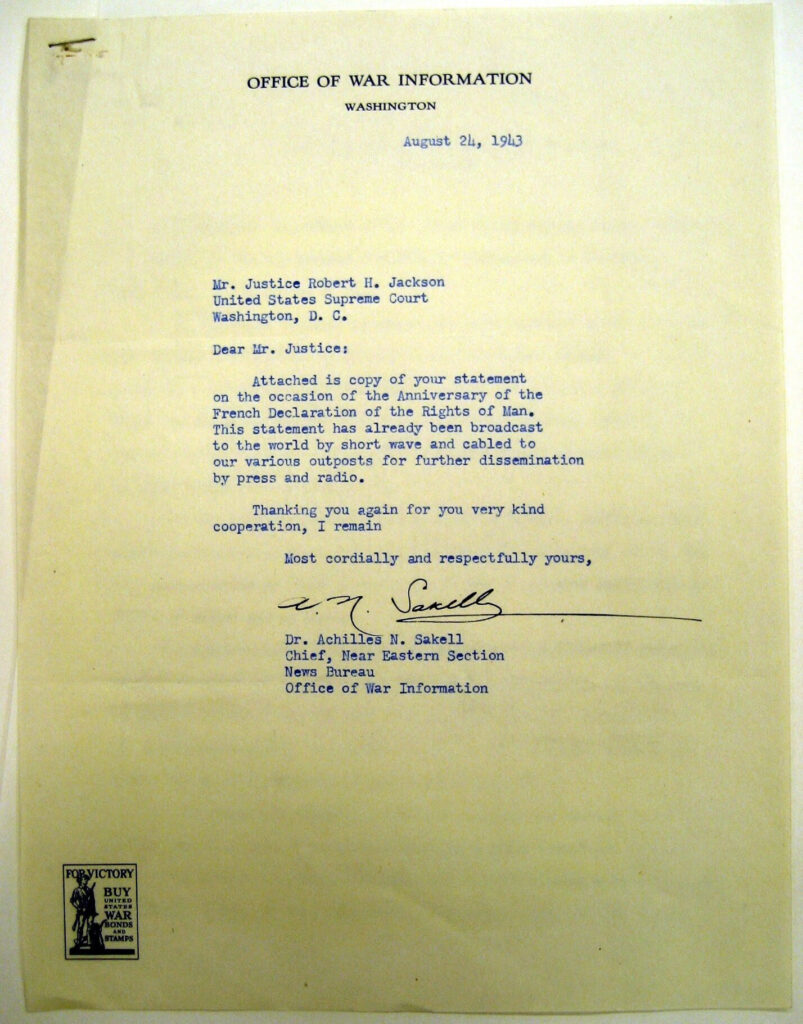

Robert H. Jackson was, at this time, a twenty-one-year-old law apprentice. He worked in Jamestown for two lawyers, Frank H. Mott and Benjamin S. Dean.

Jackson, looking out a Mott & Dean office window, saw the strikers advance on the Broadhead mansion. Jackson saw “old man Broadhead” sitting in shirt sleeves on the front porch and thought he might be in danger. Jackson saw Broadhead walk down from the porch and speak to the strikers. As Jackson recalled it decades later, “[t]hey respected his courage so much that the whole affair broke up right then and there.”

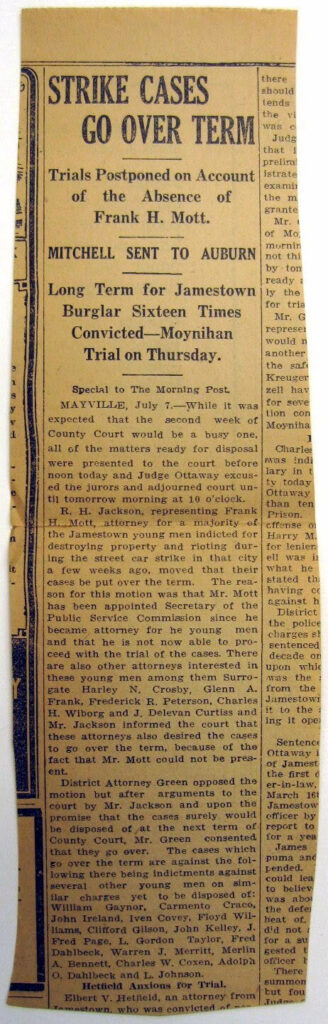

Criminal prosecutions began in the early days of the strike. On May 2 and 3, 1913, men were arrested for sawing down Street Railway trolley poles and short-circuiting tension wires.

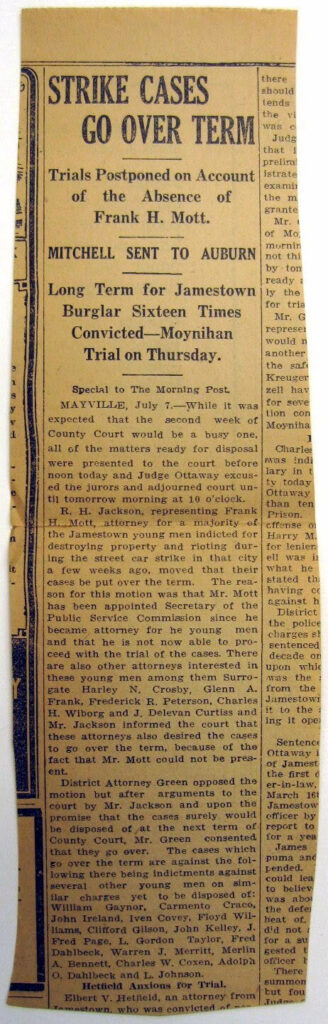

Frank Mott, who was counsel to the local labor council, appeared in Chautauqua County’s courthouse in Mayville on behalf of four arrested men. He argued that the evidence was insufficient and tried, unsuccessfully, to get the charges dismissed. The judge then set the cases for trial in July 1913. Mott arranged for his clients to be released on bail until then.

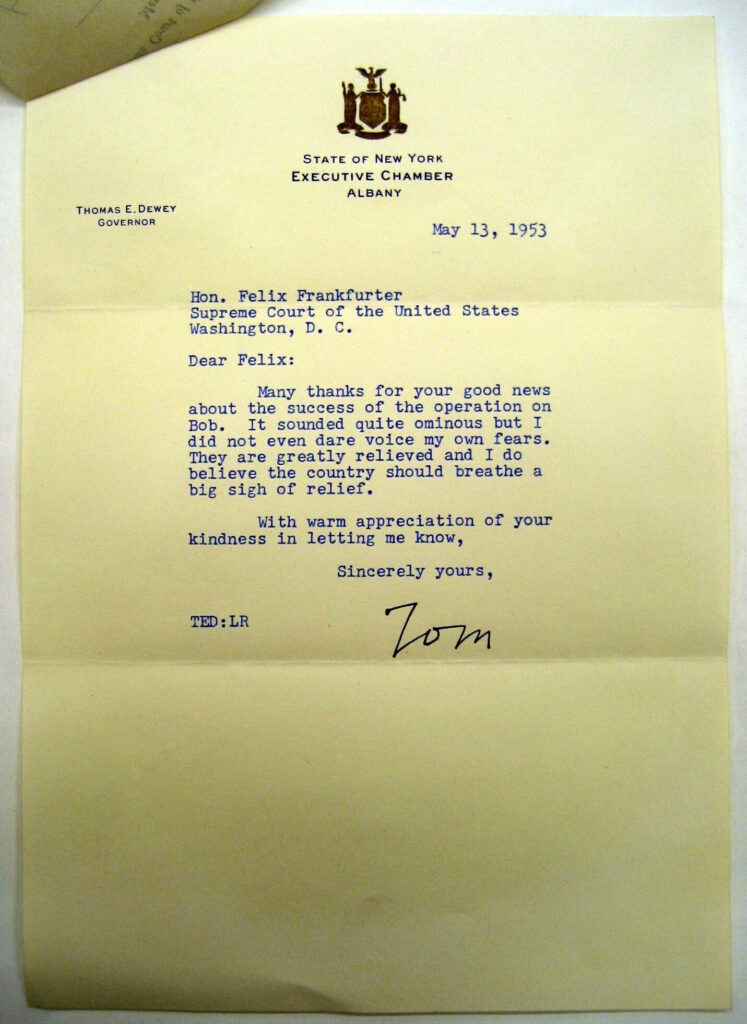

Frank Mott, a prominent lawyer in Chautauqua County, also was a significant figure in statewide Democratic Party politics. He was a strong supporter of New York’s new governor, his friend and fellow democrat William Sulzer. Those connections led the Up-State Public Service Commission to announce on June 10, 1913, that it was appointing Mott to be its new Secretary.

Less than a month later, Robert Jackson appeared in County Court in Mayville on Mott’s behalf. Although Jackson had completed law school a year earlier, he still was finishing out, as an apprentice, his required third year of law training. He had not yet taken the bar examination and been admitted to law practice. But now he was, in fact, representing clients in criminal court.

Jackson asked the judge, Arthur B. Ottaway, to put the trials of Mott’s clients over until the court’s September term. Jackson explained that Mott was not available then because of his Public Service Commission appointment.

The district attorney, Edward J. Green, opposed Jackson’s request. Green wanted to try the cases then and there. But after hearing Jackson’s arguments, including that the other defense attorneys who were present also wanted the delay and his promise that the cases would be tried in the September court term, the prosecutor relented. Judge Ottaway then granted Jackson’s requested continuance.

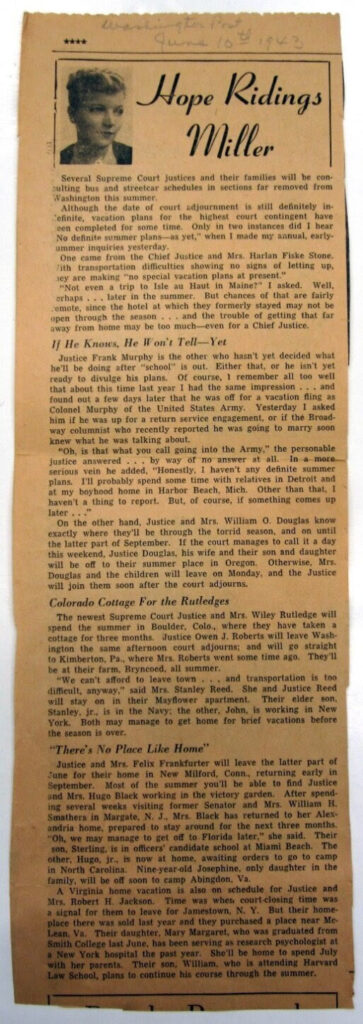

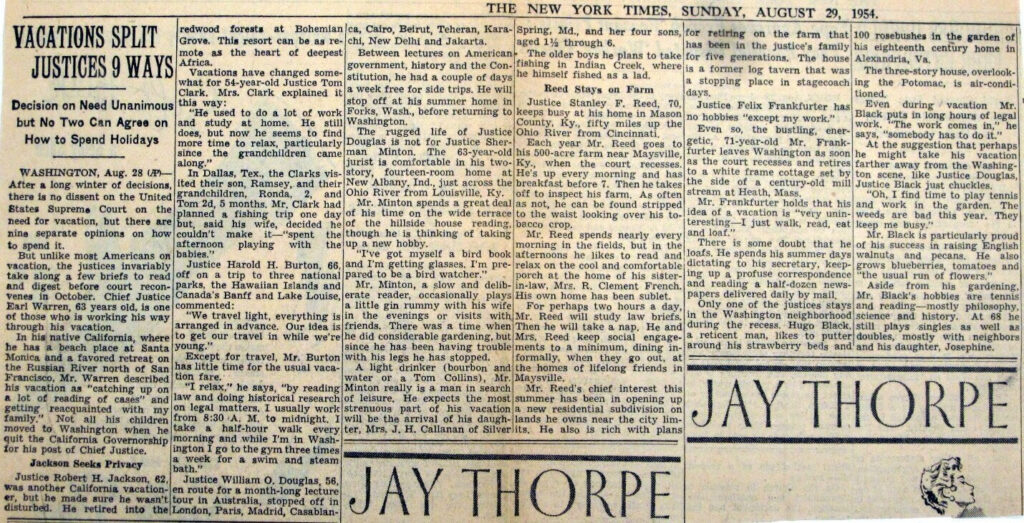

In July 1913, that decision freed Robert Jackson, the lawyers, and some of the defendants to enjoy some of the month of August.

I hope that you will get a continuance in your work schedule during the next few weeks and be able to do the same.