In Spring 1952, United States President Harry S. Truman directed Secretary of Commerce Charles W. Sawyer to seize the nation’s steel mills and keep them operating.

Truman was acting ahead of an impending steelworkers’ strike that would have shut the mills down, stopping steel production in the U.S. Truman concluded that it was vital for national security to prevent that, because steel was central, obviously, to arming U.S. forces then fighting in the Korean War, and to staying ahead of the Soviet Union in the nuclear arms race.

The steel companies responded to the seizure by filing a federal lawsuit. They argued that the president had neither constitutional nor statutory authority to seize their private property.

The case soon moved, expedited, to the U.S. Supreme Court.

The Court heard oral arguments in the “Steel Seizure Cases” (as they were nicknamed then) on Monday, May 12, and Tuesday, May 13, 1952.

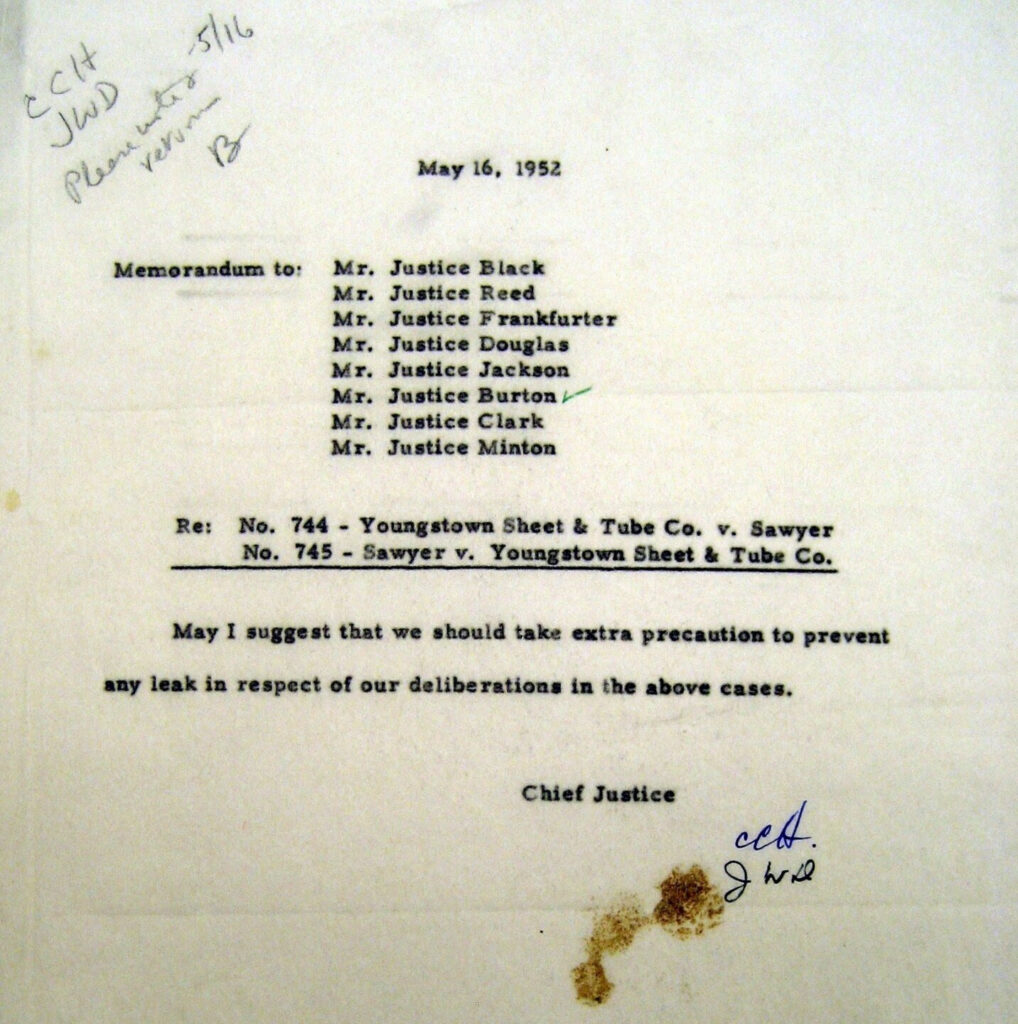

At the end of that week, on Friday, May 16, Chief Justice Fred M. Vinson sent a memorandum to each of the eight associate justices.

The Chief Justice expressed hope that no information concerning the justices’ deciding would leak out of the Court. He asked, implicitly, each justice to do what he could to prevent leaking: “May I suggest that we should take extra precaution to prevent any leak in respect of our deliberations in [these] cases.”

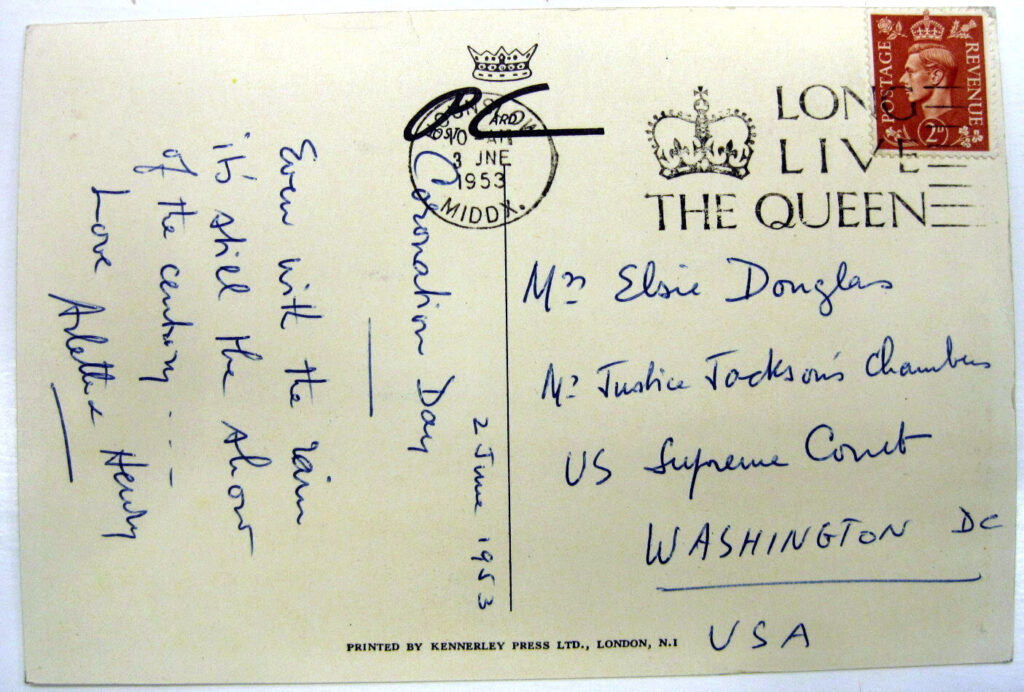

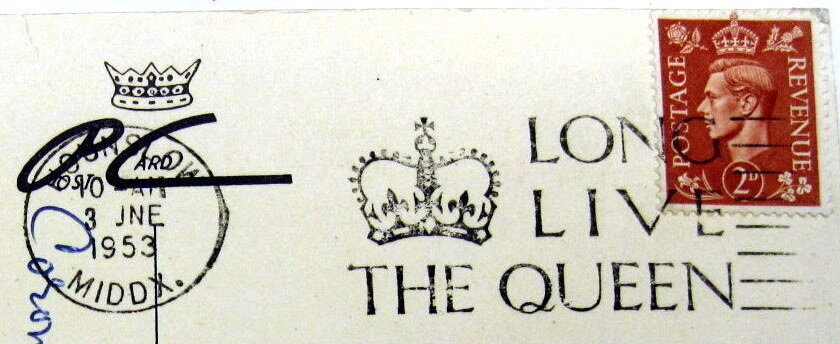

An archived document shows that when one of the eight, Justice Harold H. Burton, received and read this memorandum, he sent it on, perhaps immediately, to his two law clerks, Charles H. Hileman and John W. Douglas. Justice Burton penciled a note on the memorandum, asking the clerks to “Please note + return.”

They did—Hileman and Douglas each initialed the memorandum and then returned it to Justice Burton.

On that Friday afternoon, the Justices met in their private conference. They discussed the steel cases and each voted. They decided, by a 6-3 vote, that Truman had acted illegally.

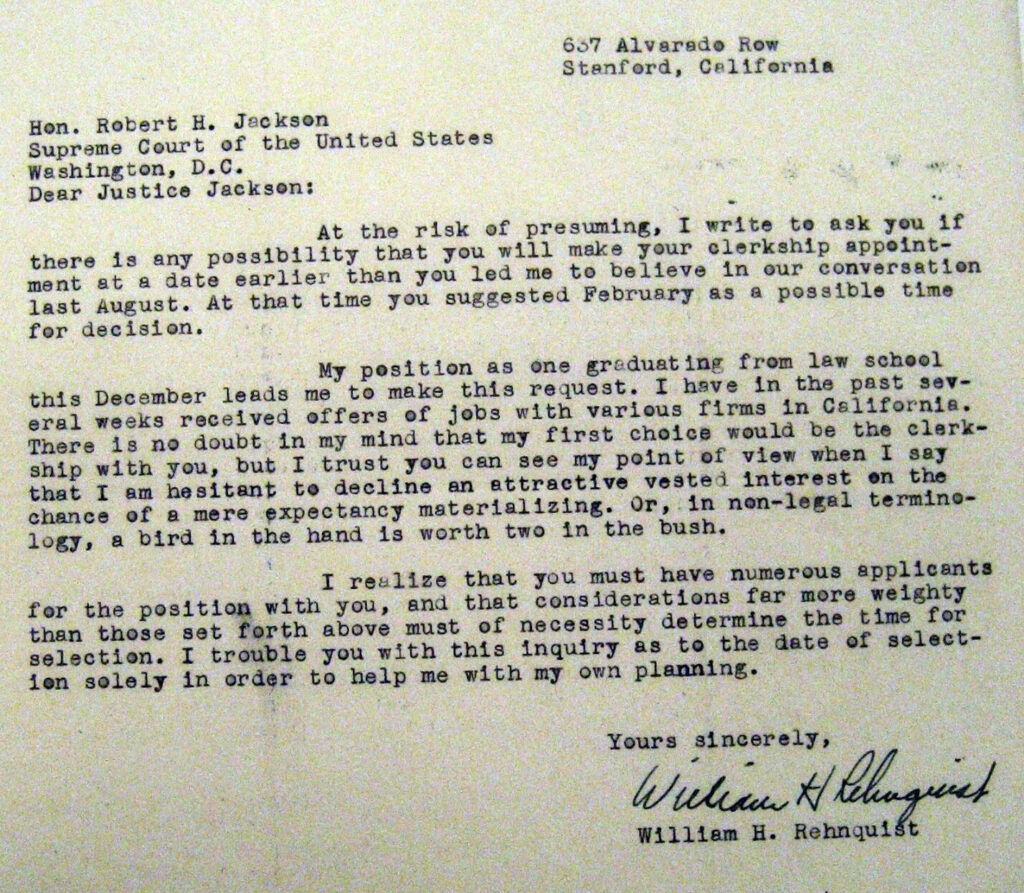

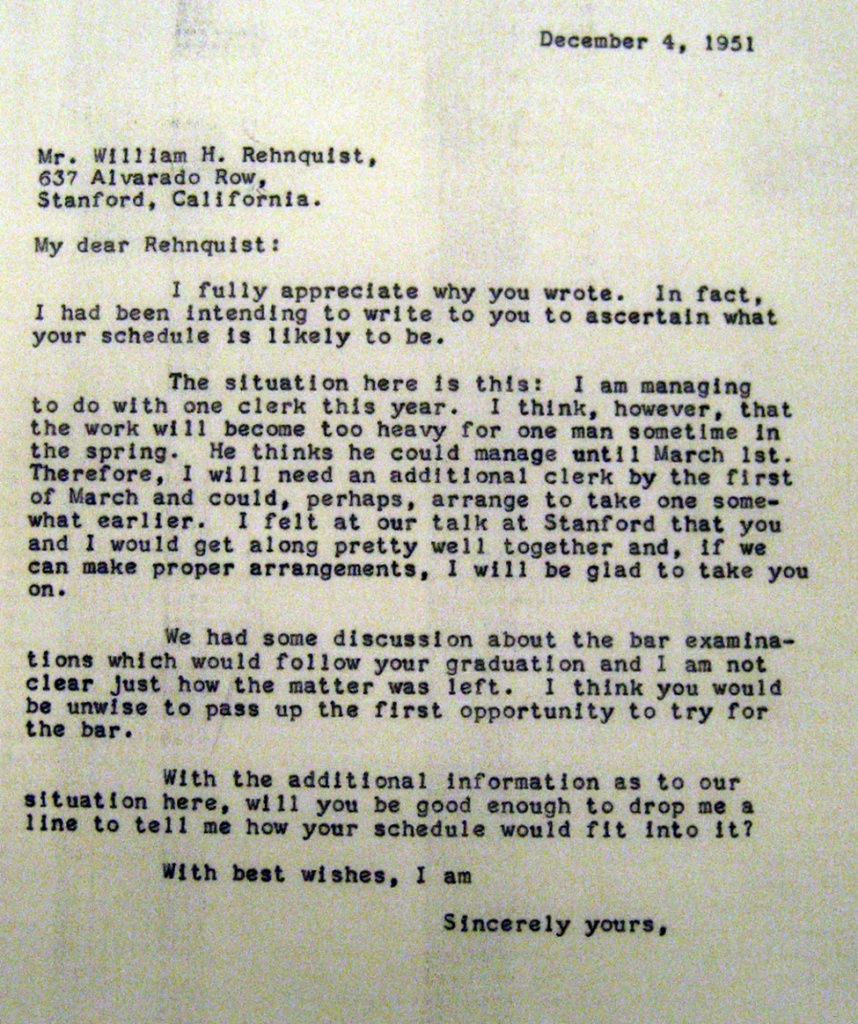

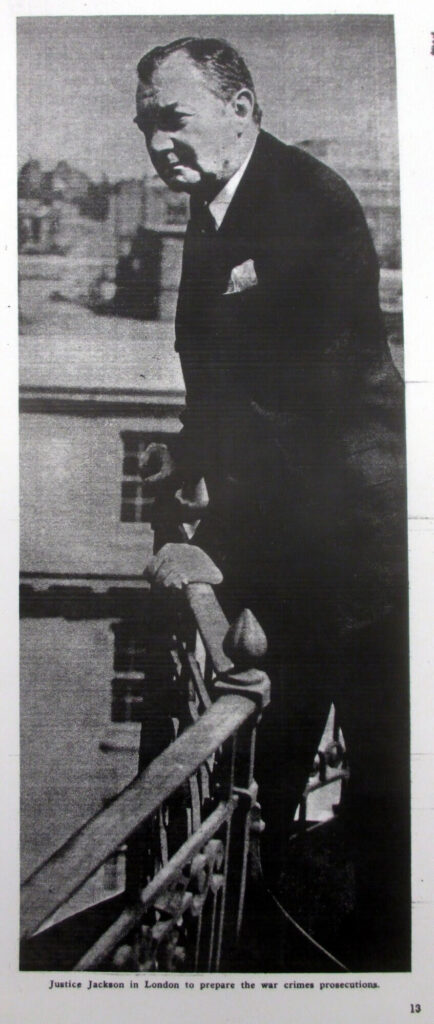

After the conference, Justice Robert H. Jackson returned to his chambers. His law clerks George Niebank and Bill Rehnquist were waiting for him, eager to hear how the Court would be deciding the momentous case. “Well, boys,” Jackson told them, “the President got licked.”

I feel confident, having met and interviewed Hileman, Douglas, Niebank, and Rehnquist when they were accomplished senior lawyers, about the Steel Seizure Cases and other topics, that in 1952 they were not leakers.

Indeed, based on having known and/or interviewed many former Supreme Court law clerks, I find it hard to imagine that any of them, in 1952 or in 2022 for that matter, would make an unauthorized leak of information, at least beyond telling their spouses, about a case while it was pending.

I think that none would do it because each is a person of high integrity, including about obeying the Court’s nondisclosure rules. (These days, among other measures and warnings, each law clerk signs a non-disclosure agreement at the start of her employment.) And I think that any law clerk who was tempted, somehow, to leak about a pending cases would pull back because of concerns about getting caught and destroying an anointed legal career just as it was getting started.

That’s still my bet today.