In 1935, the United States Congress passed and President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed into law the Social Security Act. It was a momentous piece of welfare legislation, designed to minimize the human suffering caused by unemployment and by old-age poverty. The law attacked these problems with new federal taxes on employers and employees, with expenditures and credits to encourage States to enact unemployment tax and compensation systems, and with guarantees of and expenditures for old-age pensions.

Private business interests, objecting to these new regulations, filed federal lawsuits attacking the constitutionality of both parts of the Social Security law. In 1937, after mixed judgments in federal courts of appeals, the U.S. Supreme Court took the cases.

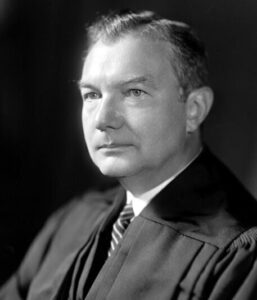

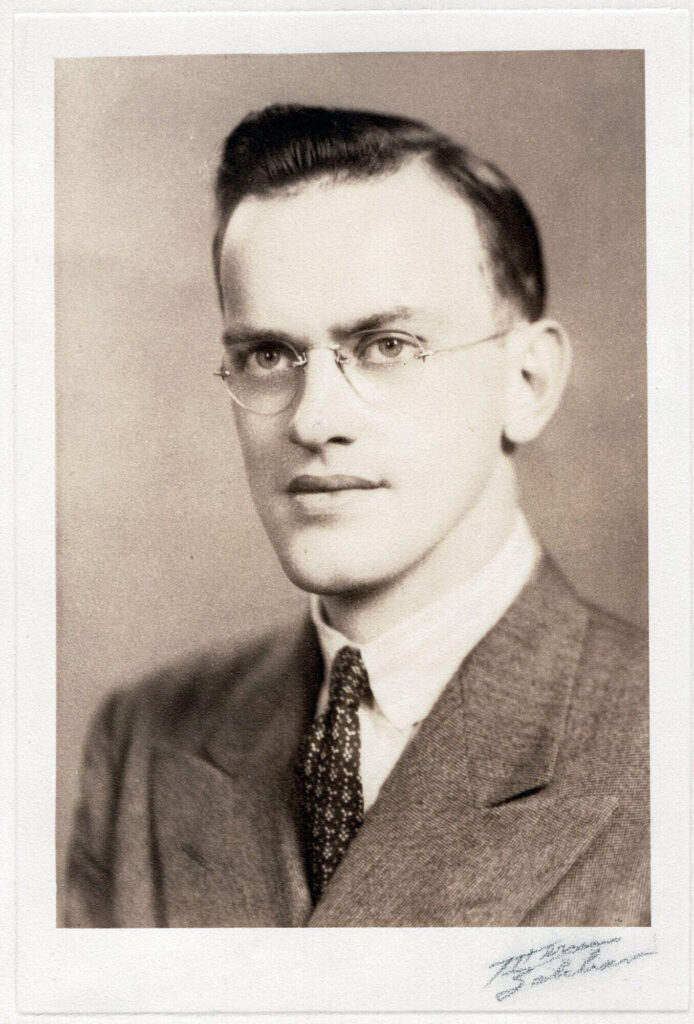

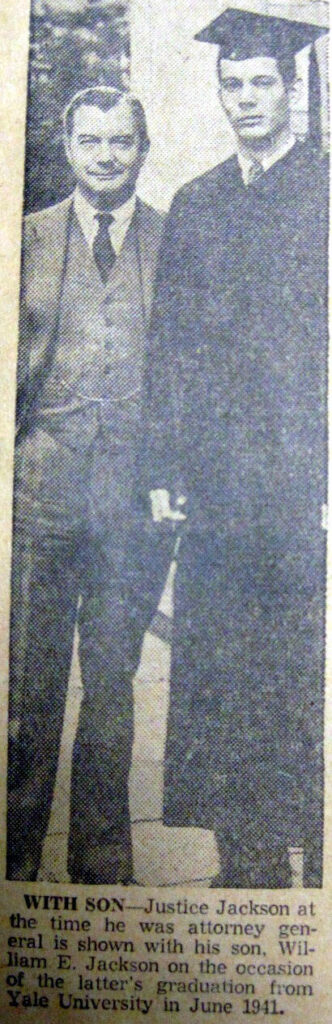

Assistant Attorney General (Antitrust Division) Robert H. Jackson and DOJ attorney Charles E. Wyzanski. They argued Steward Machine Company v. Collector of Internal Revenue, on the constitutionality of the Social Security Act taxes on employers, on April 8 and 9, 1937. They argued Helvering v. Davis, on constitutionality of Social Security’s old-age benefits and the employer taxes that pay for them, on May 5.

The Court’s decisions came swiftly.

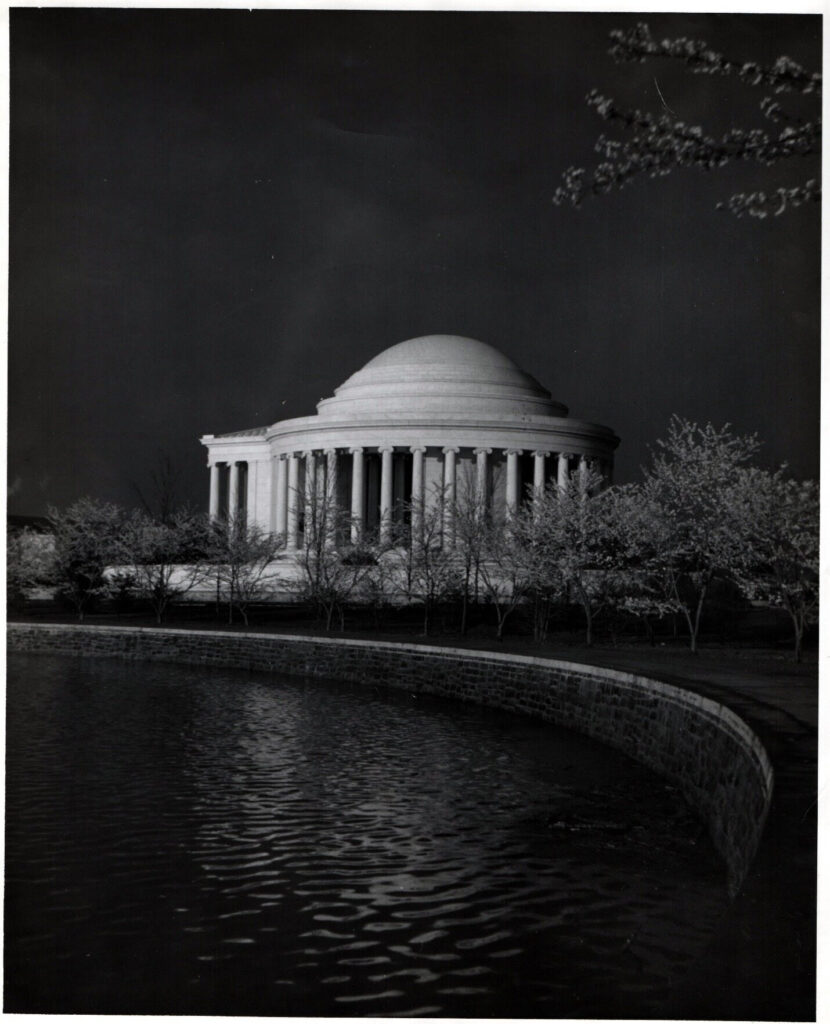

On Monday, May 24, 1937—on this date eighty-five years ago—the justices took the bench at noon. Spectators, anticipating the decisions, had been there for hours. Robert Jackson, Charles Wyzanski, and many other government officials were there too.

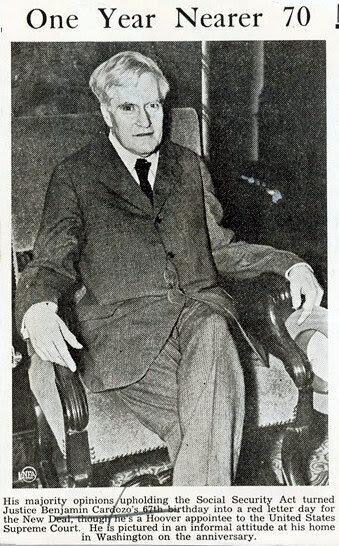

Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes, looking to his left to the far end of the bench, nodded to the junior justice, Benjamin N. Cardozo. Cardozo announced that he had been instructed to deliver the opinion of the Court in the Steward Machine Company case.

A buzz went through the courtroom. The crowd recognized immediately that the Court was upholding the constitutionality of Social Security’s unemployment insurance taxes and connected provisions—Cardozo announcing the decision could mean nothing else.

The decision was 5-4. Justice Cardozo, announcing the Court’s opinion, spoke with, for him, atypical clarity and force. Justice James C. McReynolds then spoke extemporaneously, stating his dissent, and that “the Union is being destroyed.” Justice George Sutherland then announced his dissent, which Justice Willis Van Devanter joined, on a narrow issue. Justice Pierce Butler then announced his more sweeping dissenting opinion.

Justice Cardozo then announced his opinion for the Court in Helvering v. Davis. It upheld the constitutionality of Social Security’s old-age benefits and employer taxes. The vote was 7-2. Cardozo announced the dissenting votes of Justices McReynolds and Butler, who did not write opinions.

Justices then announced decisions in six other cases, and then they recessed for the day.

Some celebrations occurred.

Justice Cardozo, who coincidentally turned sixty-seven that day, posed (or maybe he had done so that morning) for a press photograph at his apartment. If he celebrated his birthday at all, he likely did it quietly.

Robert Jackson and Charles Wyzanski accepted numerous congratulations, first at the Court and, later, back the Department of Justice.

In one sense, they had done very much—they had, by winning, ensured the survival of one of the U.S.’s most decent laws.

But Jackson and Wyzanski were, of course, merely (excellent) advocates. The Court rendered the judgments. And so the Court as an institution, and specifically the five and the seven justices who were in the respective decision majorities, did much more than the lawyers had.

But really even the justices—the Court—did not do very much. And properly so. The Court’s decisions in Steward Machine and Davis, which were part of the Court’s turn in spring 1937, simply showed restraint. The decisions recognized the breadth of federal powers under the Constitution. The decisions respected the public majorities and their elected leaders who had used these powers seriously, to promote….

Well, it’s right there in the name of the law: Social Security.